Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

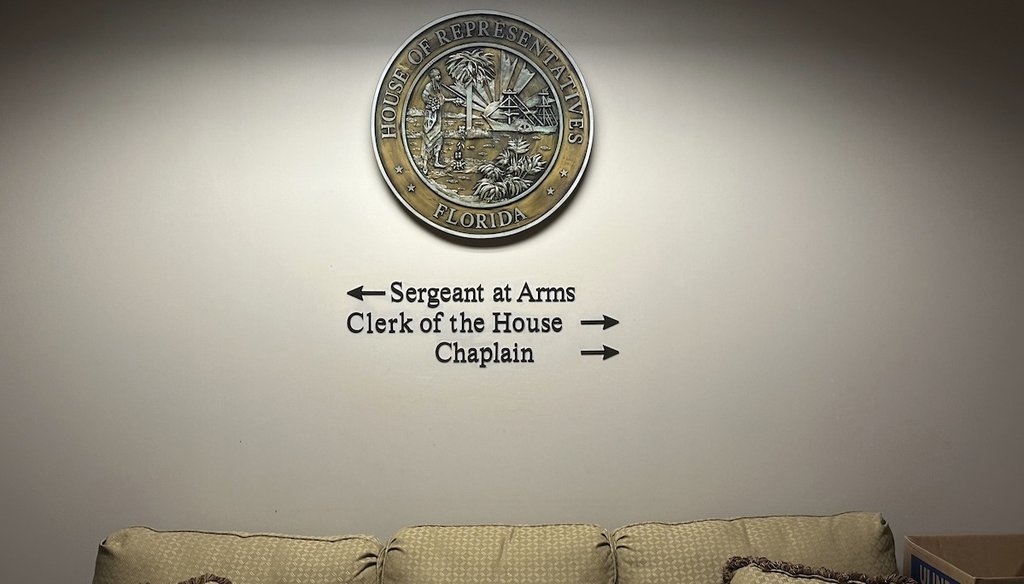

A sign directs the way to the House chaplain’s office in the Florida Capitol on March 7, 2024, in Tallahassee, Fla. (AP)

If Your Time is short

- Education historians said the notion that the founders intended for a religion-based public schooling system is an increasingly common misconception.

- The notion has gained traction amid high-profile incidents including a taxpayer-funded church-sponsored charter school in Oklahoma, a lawsuit over whether public high school coaches can pray at games in Washington, and this provision for chaplains in Florida schools.

- The reality is not so simple, they said.

Before signing into law a measure allowing religious chaplains in public schools, Gov. Ron DeSantis said the initiative brought Florida closer to what the nation's founders wanted for educating youth.

"When education in the United States first started, every school was a religious school. That was just part of it. Public schools were religious schools," DeSantis said at an April 18 news conference. "There’s been things that have been done over the years that veered away from that original intent," he continued, "but the reality is I think what we are doing is really restoring the sense of purpose that our Founding Fathers wanted to see in education."

Education historians said the notion that the founders intended for a religion-based public schooling system is an increasingly common misconception. It's gained traction amid high-profile incidents including a taxpayer-funded church-sponsored charter school in Oklahoma, a lawsuit over whether public high school coaches can pray at games in Washington, and now this provision for chaplains in Florida schools.

The reality is not so simple, they said. The founders did not establish a public education system, which really didn't get started for another 50 or so years. And when public schools began, they did not employ chaplains.

That does not, however, mean religion was absent from early schooling.

"The answer is, perhaps expectedly, nuanced and hard to capture in a single sentence," said F. Chris Curran, director of the Education Research Policy Center at the University of Florida. Schooling began in the colonies before the founding of the nation, and much of it was closely tied to religion, Curran said by email.

"An act passed in Massachusetts in 1647, ‘Old Deluder Satan Act,’ is often cited as the first public education in what would become the US," Curran wrote. "Requiring communities across the state to hire teachers, the general purpose of the act was to ensure a level of literacy sufficient for reading the Bible and preventing individuals from falling prey to 'the old deluder, Satan.’"

Schooling was not organized at that time, though. Most children did not have access to education beyond what their parents could provide, which ranged from private tutoring to boarding schools, according to a history of public education by Bellwether. By the time of the American Revolution, some Northeast towns had free local schools paid for by residents, "but this was not the norm," according to a frequently cited history from the Center on Education Policy, a nonpartisan group that researches and analyzes education issues.

As leaders crafted the Declaration of Independence and, later, the Constitution, many had strong views about the importance of schooling and the role of religion in it.

"Some Founding Fathers, such as Benjamin Rush, really did want public schools to teach children how to be better evangelical Protestant Christians," said Adam Laats, professor of education and history at Binghamton University, part of the State University of New York system. "But others, like Thomas Jefferson, thought public schools had to remove all religious ideas entirely."

Several advocated for a formal education system, Laats said. Jefferson and others contended that the fledgling nation would depend on an educated populace that understood their roles as citizens in a democracy.

But universal public education didn't emerge at that time, and the founders did not establish guidance on the matter, as Laats wrote in a column for The Washington Post. Despite their interest in the subject, the founders "had nothing to say about public education" in the documents establishing the nation, said Sevan Terzian, professor of social foundations of education in UF's School of Teaching & Learning.

"Public education didn't really start until the 1830s," Terzian said. That's when Horace Mann, secretary of the Massachusetts board of education, came up with the "common school" concept that is associated with the system the nation now has.

"By the mid-1800s, most states had accepted three basic assumptions governing public education: that schools should be free and supported by taxes, that teachers should be trained, and that children should be required to attend school," Wendy A. Paterson, dean of the Buffalo University School of Education, wrote in an article for the school's 150th anniversary.

Those earliest schools paid for withpublic funds "were not religious schools, although most schools opened with prayers or Bible reading," education historian Diane Ravitch, founder of the Network for Public Education, said via email. "But such activities were incidental, not the purpose of the schools."

The common schools, though, sought to provide a unified sense of moral values to connect citizens, and those generally aligned with the majority Protestant Christian values of the time, Terzian said: "For most of the 19th century, most of public education was implicitly Protestant Christian, and some of it was explicit."

That caused denominational rivalries, which led to the establishment of private religious schools. Catholic leaders complained that public schools used a Protestant Bible, Ravitch said, "and there were violent clashes between the two major religious groups. Catholics, mostly Irish and recent immigrants, determined to build their own school system, where only Catholic materials would be used."

The focus of public education shifted as the nation's economy diversified, along with its demographics, Terzian said. "Schools became places for preparing youth or the transition into a growing industrial economy," he explained. Still, prayer remained common. Officials aimed to have prayer general enough that most could agree on it regardless of their denomination, Laats said.

With the number of non-Christian religions in the nation increasing, views on that emphasis changed over time, too.

"Eventually, the rhetorical commitment to nonsectarianism was fulfilled, much to the displeasure of those who had wished to support a national religion," said Jack Schneider, an education professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

In the 1960s, the U.S. Supreme Court made clear in rulings that when allowing religious aspects into schools, government should not be viewed as endorsing it, Laats said. Since then, he added, Americans’ views have solidified around the free practice of religion.

Even if prayer is allowed, or a religious organization is permitted in a school, the same opportunities exist for all students without giving preferences. For instance, if a group like the Fellowship of Christian Athletes is permitted to meet, so, too, are other clubs and organizations with religious affiliations.

Laats suggested that DeSantis might be testing that perspective by stating that theSatanic Temple, which has shown interest in participating in the chaplain program, is not a real religion and would not be included.

The future of religion — and chaplains — in the public schools might still be evolving, a question for the courts to decide. But historians say the truth of the past is that public schools were not established as religious by the founders.

Jeffrey S. Solochek is the Tampa Bay Times’ education reporter.

Our Sources

Please see links in story.