Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

Gilbert Stuart's portrait of George Washington

Five years ago, we published an article inspired by a visit to the restored colonial city of Williamsburg, Va., where we discovered a gem of a book: George Washington’s Rules of Civility.

Somewhat lightheartedly, we published "What Would George Do?" on President’s Day as a counterpoint to the incivility that had come to dominate his namesake city more than two centuries later.

In today’s bitter political climate, we thought we’d revisit these rules to see how much better or worse things have gotten.

The 110 rules of civility predated Washington’s presidency by more than four decades. They mostly came from a French manuscript dating from 1595, titled Good Manners in Conversation Among Men, which in turn descended from an Italian book published by a Catholic cleric in 1552.

The rules became associated with the future first president through a notebook that 13-year-old George had assembled in 1745. At the time, it was common for students in the colonies to copy lists of social rules and morals.

Some of the "civil" behaviors addressed mundane things like concealing bodily functions. But a handful, we thought, echoed across the centuries as advice for contemporary purveyors of political rhetoric. Namely:

• Show not yourself glad at the misfortune of another, though he were your enemy.

• Mock not, nor jest at anything of importance. Break no jests that are sharp and biting, and if you deliver anything witty and pleasant, abstain from laughing thereat yourself.

• Associate yourself with men of good quality if you esteem your own reputation. For ‘tis better to be alone than in bad company.

• Let your conversation be without malice or envy, for ‘tis a sign of a tractable and commendable nature. And in all causes of passion admit reason to govern.

• Speak not injurious words, neither in jest nor earnest. Scoff at no one, although they give occasion.

"President Washington would be terribly saddened to see the continued decline of civility in the public arena," James H. Mullen Jr., the president of Allegheny College, which offers a Prize for Civility in Public Life. "It is sapping strength from our democracy."

In interviews, experts in American political discourse and ethics agreed that things have gotten much worse. Americans generally feel the same way: Last year, with only modest variations depending on the respondent’s party affiliation, 68 percent of those surveyed believed that "the overall tone and civility in American politics over recent years" was getting worse.

The experts cited President Donald Trump as a major motivating factor.

Civility "is more than toleration," said Richard J. Mouw, a professor of Christian philosophy and ethics who served for two decades as the president of Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, Calif.

"Toleration is a pattern of live-and-let-live," he said."Genuine civility has to be grounded in empathy —a genuine desire to promote the well-being of others. It has a moral — and I should add — spiritual, component."

Often, people learn the rules of civility growing up. But that can be tricky in the contemporary United States.

"You could say that etiquette is the original homeschooling," said Keith J. Bybee, a political scientist at Syracuse University's Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs and author of How Civility Works. "In a static and homogenous society, one would expect homeschooling in civility to yield a consensus on the norms of appropriate public behavior. But the United States is not such a society."

In a country as dynamic and heterogeneous as ours, Bybee said, "people regularly learn different rules of civility at home. And even when they learn the same rules, there is no way to ensure that they agree on the application of those rules to concrete circumstances."

Recent presidents, despite the inevitable divisions in society on their watch, have tended to be conciliators rather than agitators. Trump was an agitator from the start, experts said.

"Beginning with his behavior in the Republican primary debates, continuing through the general election, and now in the White House, Donald Trump had not just ignored but delighted in breaking the norms of civil political behavior," said Cornell W. Clayton, director of the Thomas S. Foley Institute for Public Policy and Public Service at Washington State University and author of Civility and Democracy in America: A Reasonable Understanding.

Examples of Trump acting outside of shared norms for modern presidents include his taunting nicknames for political opponents ("Little Marco," "Lyin’ Ted"), his chants of "lock her up" against defeated Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, and his consistent exaggerations and falsehoods, scholars said.

"He has acted to accelerate, rather than serve as a brake on, the erosion of existing norms of political civility," Clayton said.

Before Trump, one of the most uncivil political moments came in 2009 when Rep. Joe Wilson, R-S.C., called out, "You lie!" during President Barack Obama’s address to a joint session of Congress.

But "at least that was based on a disagreement about policy," said Christopher F. Zurn, who chairs the philosophy department at the University of Massachusetts-Boston.

Sean Wilentz, a Princeton University historian, said that civility has "utterly collapsed in the White House. The president's supporters wanted malice, envy, and passion from him, and he's delivered."

Mouw, the former seminary president and author of Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World, said we are "much worse off today."

George Washington’s rules, he said, "read like direct reprimands to behavior that is rampant in our contemporary climate — stimulated by bad behavior at the very top of the leadership ladder."

Mouw added that neither the left nor right is immune from the decline in civility. "Even in much of the late-night comedic commentary, which I frequently enjoy, There seems to be a pervasive cynicism on many levels. Not many public figures are modeling ‘good quality.’ "

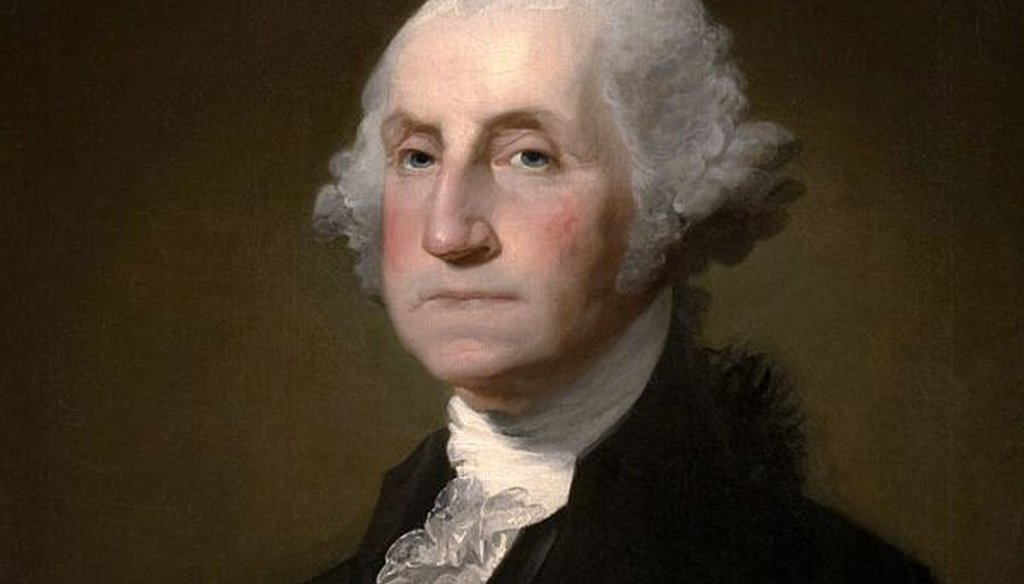

A lithograph cartoon depicting Preston Brooks' attack on Charles Sumner in the Senate in 1856 (Wikimedia Commons).

All this said, several of these same experts urged critics of today’s political climate to refrain from sky-is-falling rhetoric.

The country’s first two centuries were not always peaches and cream.

"The framers of the Constitution thought the country was teetering on the brink of barbarism, with the crass and interest-ridden behavior of people in the states tearing away at the last vestiges of decorum," Bybee said. "In every generation since the founding, there have been complaints about deteriorating standards of public behavior. And I am confident that disagreements over how we ought to behave will continue far into the future."

Campaigns two centuries ago, such as the election of 1800, were vitriolic, Clayton said. Subsequently, "Andrew Jackson was accused of murder and adultery by John Quincy Adams supporters, and Adams was accused of being a pimp by Jackson’s supporters," he said. "Obviously, the 1850s and 1860s were bad, with fistfights in Congress and then a bloody Civil War."

Even as recently as the 1960s, he noted, America was rocked by successive political assassinations, violent reactions to the civil rights movement, and campus riots over the Vietnam War. "So the general state of civil behavior has been far worse during some previous periods in history," Clayton said. "We are not that bad yet."

Some degree of political conflict is necessary for a functioning democracy.

Clayton said there are legitimate and deeply-held disagreements about how to deal with a globalized, post-industrial economy that offers fewer secure jobs and stagnant compensation. The demographic and cultural changes that come as a result inevitably foster division and passions.

"People are often confused about the relationship between incivility and political division," Clayton said. "They think that if we could simply be more civil, more polite, and more cooperative, then we could come together to solve the major political challenges that divide us. But the reality is the opposite. The reason the norms of civil political behavior have eroded over the past few decades — and the reason they eroded during previous periods of history — is precisely because we are so deeply and closely divided as a country. "

Some see today’s hand-wringing over lost "manners" as misguided, since a rigid demand for manners in politics can be used to paper over justifiable demands to rectify grievances.

"I’m in favor of partisanship and distrustful of the subjectivity of appeals to manners, which are often semi-disguised rules that one social class imposes on another," said John H. Summers, who has taught religion and American public life at Boston College, Harvard University, Columbia University, and the Cooper Union.

The short-term outlook is grim.

"I am particularly concerned that this trend will drive young people away from politics," said Mullen, the Allegheny College president, who keeps a copy of Washington’s rules on his desk. "This generation is passionately committed to making a difference for the good, but the meanness and incivility of our politics is playing a role in driving them from the arena. The consequences for our democracy are very serious."

Clayton saw more trouble ahead, especially if the probe into Russian interference closes in on Trump. If that happened, he would "expect the president to intensify his assault on these and other norms in an effort to delegitimize the opposition. That will produce its own backlash and a more militant response from those who oppose Trump."

But some saw a bit of sunlight amid the clouds.

"For all of the attention being given to incivility on our campuses, there are hopeful signs in the younger generation," Mouw said, pointing to televised interviews with teenage survivors of the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida. He saw similar "respectful engagement"r among students he oversaw at a recent interfaith dialogue.

"If voters were to reject uncivil rhetoric, that would help," said Kim Fridkin, an Arizona State University political scientist who’s affiliated with the National Institute on Civil Discourse. "Or, if people were convinced that uncivil rhetoric had negative effects on people and society, perhaps people would reject incivility. I think we need people in high profile positions to model civility in politics. This could help."

Historically speaking, however, periods of consensus and civility have often followed major upheavals, such as crises, wars and social exhaustion, Clayton said.

"Can political leaders help us through this period today by resisting the temptation to purposely aggravate divisions and angers for short-term political gains? Yes," Clayton said. "Will they? I don’t know."

Our Sources

PolitiFact, "What would George do?" Feb. 17, 2013

George Washington's Rules of Civility, edited by John T. Phillips II, published 2003 (Goose Creek Productions)

CNN, "Poll: Majority say civility in political debate worsening," June 20, 2017

CBS News poll, toplines, June 2017

Email interview with Kim Fridkin, Arizona State University political scientist affiliated with the National Institute on Civil Discourse, Feb. 16, 2018

Email interview with Richard J. Mouw, professor of Christian philosophy and ethics, former president of Fuller Theological Seminary, and author of Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World, Feb. 15, 2018

Email interview with Keith J. Bybee, political scientist at Syracuse University's Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs and author of How Civility Works, Feb. 15, 2018

Email interview with Cornell W. Clayton, director of the Thomas S. Foley Institute for Public Policy and Public Service at Washington State University and author of Civility and Democracy in America: A Reasonable Understanding, Feb. 16, 2018

Email interview with Christopher F. Zurn, chair of philosophy at the University of Massachusetts-Boston, Feb. 16, 2018

Email interview with Sean Wilentz, Princeton University historian, Feb. 16, 2018

Email interview with John H. Summers, who has taught religion and American public life at Boston College, Harvard University, Columbia University, and the Cooper Union, Feb. 16, 2018

Email interview with James H. Mullen Jr., president of Allegheny College, which offers a Prize for Civility in Public Life, Feb. 18, 2018