Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

Former President Barack Obama speaks during the funeral for the late Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., in Atlanta on July 30, 2020. (Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP, Pool)

If Your Time is short

• The filibuster’s emergence had nothing to do with racial legislation, and it has been used against a wide variety of bills. However, historians agree that the filibuster was closely intertwined with anti-civil-rights efforts in the Senate for more than a century, thanks to repeated efforts by southern senators to filibuster civil rights bills.

Former President Barack Obama made some news when he delivered a eulogy for John Lewis, the civil rights activist and congressman from Georgia who died on July 17 after battling cancer. In his eulogy, Obama said he was open to ending the filibuster, the longstanding rule in the U.S. Senate that allows a minority of 41 senators to block action on a bill.

Obama’s declaration during the July 30 church service in Atlanta came as he argued that Lewis’ top issue – the right to vote – was under attack.

"You want to honor John? Let’s honor him by revitalizing the law that he was willing to die for," the Voting Rights Act. Obama said he supported such policies as automatic voter registration, additional polling places and early voting, making Election Day a national holiday, statehood for Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, and an end to partisan gerrymandering.

"And if all this takes eliminating the filibuster – another Jim Crow relic – in order to secure the God-given rights of every American, then that’s what we should do" Obama said.

A former Obama speechwriter, David Litt, had used almost identical language more than a month earlier when writing in the Atlantic, calling the filibuster "another relic of the Jim Crow era."

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

We wanted to know more about the history of the filibuster and its role in the Jim Crow era.

Historians told PolitiFact that the filibuster did not emerge from debates over slavery or segregation. However, they agreed that the parliamentary tactic was closely affiliated with opposition to civil rights for more than a century.

"The histories of the filibuster, civil and voting rights, and race in America are intertwined," said Steven S. Smith, a political scientist and Senate specialist at Washington University in St. Louis.

Where did the filibuster come from?

The filibuster was never "established" by a specific act; it emerged essentially by accident.

In her book, "Minority Rights, Majority Rule: Partisanship and the Development of Congress," Sarah Binder pegs the origins of the filibuster to a revision of Senate rules in the first decade of the 19th century, when senators mistakenly deleted a rule empowering a majority to cut off debate.

"Bereft of a rule to limit debate by majority vote in the 19th century, senators learned to exploit the rules to obstruct, delay, and take measures hostage for action on favored bills," said Binder, a political scientist at George Washington University and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

It took until 1917 for the Senate to enact a "cloture" rule that disempowered a single senator, or small group of senators, from stopping debate on their own. The 1917 rule empowered a two-thirds majority of senators to cut off debate and proceed to the business being blocked. That fraction was lowered to three-fifths in 1975, where it remains today. (More recently, both parties have moved to eliminate the filibuster for appointments, but it remains in place for legislation.)

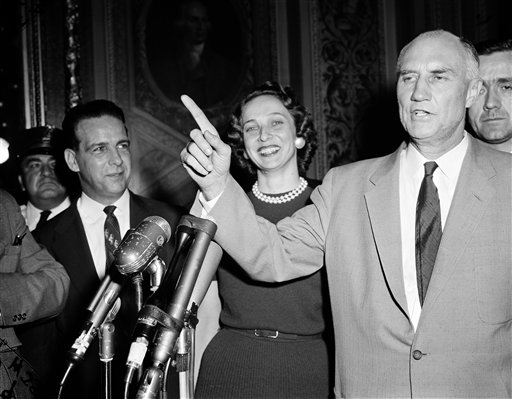

Sen. Strom Thurmond, D-S.C., demonstrates his oratory minutes after he emerged from the Senate chamber where he spoke a record-breaking 24-hours, 18 minutes, against the compromise Civil Rights bill, on Aug. 29, 1957. (AP)

How the filibuster has been used against civil rights legislation

"Exploitation of the filibuster repeatedly undermined adoption of measures supported by majorities to protect and advance the rights of African Americans for much of Senate history," Binder said.

The first period when this happened was in the pre-Civil War era, when filibusters were used against the admission of states depending on their slavery status, including California in 1850 and Kansas beginning in 1857, said Gregory Koger, a political scientist and congressional specialist at the University of Miami.

Then, during the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction eras, senators launched filibusters against civil rights bills, deployment of federal troops in southern states, and repayment of income taxes from the Civil War, Koger said.

"The last gasp of Republican efforts to ensure the political rights of southern blacks was the 1890-91 elections bill, which died in a Senate filibuster," Koger said. "The Republicans were chastened after this last effort. They were surprised by the vehemence of Southern opposition to the bill, and found that northern interest in civil rights was low."

Civil rights largely faded from the congressional agenda between the 1890s and the 1930s, but even then, the filibuster was used to block anti-lynching bills in 1922 and 1935. (Efforts to belatedly enact an anti-lynching law have been under way during the current Congress, but no law has been sent to the president yet.)

"It wasn’t until the 1950s that weak civil rights legislation was passed, and it wasn’t until 1964 and 1965 that legislation with real teeth was enacted," Smith said.

Generally speaking, pro-civil rights senators did not resort to filibustering, Koger said. One exception came in 1937, when pro-civil rights senators threatened to filibuster the resolution to adjourn for the year until Senate Majority Leader Alben Barkley promised to bring an anti-lynching bill up for a vote. Barkley relented, but the bill that came to the floor died due a filibuster.

Pro-civil-rights senators could have used filibusters to hold hostage bills valued by southerners, Koger said. But they didn't, he said, in part because northern senators had a much smaller proportion of African American constituents at the time, making the issue seem less immediately salient.

By contrast, "once southern states had imposed a vast array of voting and election advantages for white citizens, there were few politicians in the South whose careers depended on representing southern Blacks, including restoring their political equality," Koger said. With whites strongly in favor of the Jim Crow status quo, southern senators went all in on blocking civil rights legislation, including the use of the filibuster, he said.

Even the Civil Rights Act of 1965, the landmark bill that finally broke the logjam, was almost blocked by the filibuster. The bill’s proponents were able to win passage only after securing 71 votes, including 27 Republicans, to end a filibuster.

Other targets of the filibuster

Civil rights legislation has not been the only type of Senate action to become subject to a filibuster.

The very first Senate filibuster was over a bridge across the Potomac River, Koger said, and trade, tariffs, and monetary policy inspired some 19th and early 20th century filibusters.

"During the 1920s and 1930s, many filibusters were waged by progressives against perceived government handouts to big business, and for neutrality in foreign affairs," Koger said. "The 1939 movie 'Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,' in which a simple prairie patriot filibusters against a corrupt political machine, embodies this progressive image of filibustering."

For most of congressional history, Koger said, "legislators have had to invest effort and pay political costs to filibuster, so the set of issues being obstructed at any time is a record of what politicians and voters really cared about. This included race, slavery, and civil rights, but also trade, foreign affairs, monetary policy, and internal parliamentary rights."

Who favors the filibuster?

On balance, Smith said, conservatives tend to like the filibuster more than liberals do, since the filibuster makes it harder to create new federal programs, which is a fundamental goal of small-government conservatism. Liberals, by contrast, are more likely to feel constrained by the filibuster in their efforts to expand the government’s role.

Even so, "situational ethics" also play a role, Smith said.

One argument in support of continuing the filibuster is that any majority is eventually going to be back in the minority and will rue the day it made life harder for its future self. Another argument against eliminating the filibuster is that it gives any single senator greater power within the chamber. Getting rid of the filibuster would require a tradeoff of each senator’s individual leverage.

That said, historians say that the filibuster’s decades of use in opposition to civil rights has bequeathed it a historical stain.

"The repeated filibusters against civil rights legislation provide clear examples of how filibustering can be used to defend horrendous status quo policies," Koger said.

Our Sources

New York Times, transcript of Barack Obama’s remarks at John Lewis’ funeral service, July 30, 2020

U.S. Senate Historical Office, "Filibuster and Cloture," accessed Aug. 3, 2020

The Atlantic, "The Senate Filibuster Is Another Monument to White Supremacy. Tear it down," June 27, 2020

National Constitution Center, "The filibuster that almost killed the Civil Rights Act," April 11, 2016

New York Times, "Congress Moves to Make Lynching a Federal Crime After 120 Years of Failure," Feb. 26, 2020

Vox.com, "Obama: The filibuster is a 'Jim Crow relic,'" July 30, 2020

Email interview with Gregory Koger, political scientist and congressional specialist at the University of Miami, July 31, 2020

Email interview with Sarah Binder, political scientist at George Washington University and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, July 31, 2020

Email interview with Steven S. Smith, political scientist and Senate specialist at Washington University in St. Louis, July 31, 2020