Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

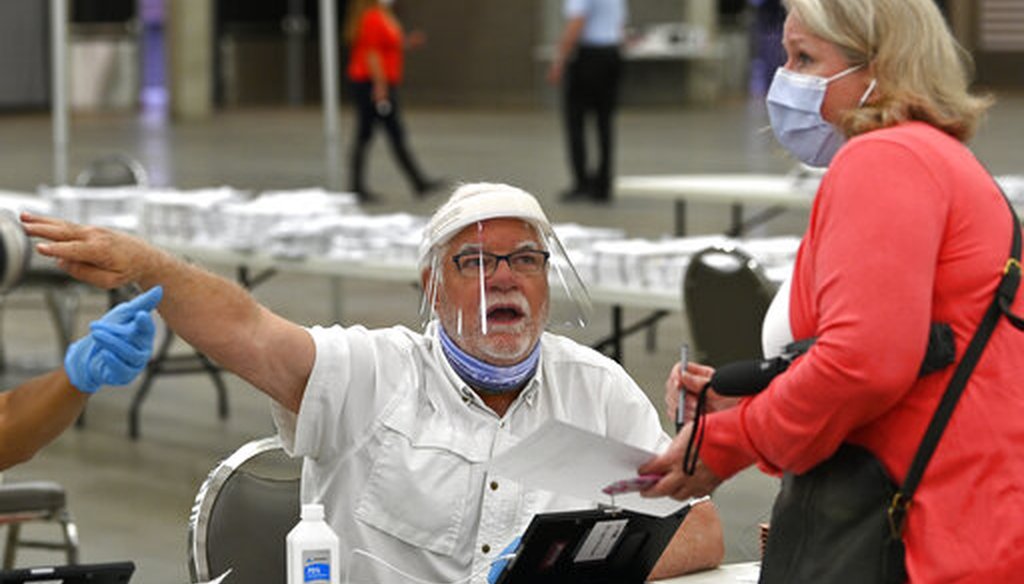

Poll workers instruct a voter on where to fill out their ballot during the Kentucky primary at the Kentucky Exposition Center in Louisville, Ky., on June 23, 2020. (AP)

If Your Time is short

• Some critics warned that a reduction in in-person voting sites in Kentucky’s June primary was a clear case of voter suppression. But these critiques often ignored that Kentucky also expanded mail balloting significantly, under an agreement between the state’s governor, a Democrat, and its secretary of state, a Republican.

• When all the votes were counted, the number of primary votes set a record and the turnout percentage was the highest in a decade.

In the days leading up to Kentucky’s June 23 primary, national figures raised alarms about the state’s Election Day voting infrastructure.

Celebrities from film director Ava Duvernay to former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams to NBA superstar LeBron James decried the closing of all but one in-person Election Day polling place in each Kentucky county.

"This is voter suppression," tweeted former Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton "We need to restore the Voting Rights Act."

The critics particularly spotlighted Jefferson County, which includes Louisville and about half of the state’s Black population.The county had only one polling place open on Election Day in Jefferson County, at the Kentucky Exposition Center in Louisville.

Observers did report scattered problems on Election Day, including delays at the University of Kentucky’s football stadium, which was serving as the main voting location in Lexington. There was also a last-minute crunch at the Louisville location that was rectified when a judge ordered the doors kept open to accommodate latecomers stuck in traffic.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

But often overlooked in the pre-election critiques was Kentucky’s significant expansion of mail balloting, under an agreement between the state’s Democratic governor, Andy Beshear, and its Republican secretary of state, Michael Adams.

And when all was said and done, primary turnout came close to setting records, both statewide and in Jefferson County.

Statewide, the number of primary ballots cast set a new record, and the turnout rate of about 33% was easily the highest in the state since the high-profile 2008 primary between Clinton and Barack Obama.

Jefferson County showed a similar pattern, with a record number of votes cast and a turnout

rate of 33%, higher than any primary since 2008.

"For the most part, it seems like things went smoothly enough, and the public trusts the outcome," said Laura Cullen Glasscock, editor and publisher of The Kentucky Gazette, which covers politics in Kentucky.

Talking to reporters after the election, Adams, the secretary of state, expressed satisfaction with the way things turned out. "I’ll confess, I was pretty nervous about it going well, and it went well beyond my wildest dreams," he said.

In particular, majority-Black precincts in Jefferson County saw turnout increases, according to analysis by the Louisville Courier-Journal.

In Louisville's 83 majority-Black precincts, 38% of registered voters cast a ballot in 2020, several percentage points higher than the rate statewide or in Jefferson County as a whole. That percentage was also higher than the 32% in those precincts in 2016 and the 25% in 2019, the newspaper found. The analysis found similar increases in the precincts where 25% to 50% of the population is Black.

And these increases were driven by heavy use of mail ballots, the Courier-Journal found. In Jefferson County, more than 132,000 mail ballots were cast, comprising roughly 88% of the vote. Observers said that at the 1.3 million square foot exposition center in Louisville, waits for voters were rare.

"When you make voting easy, and not so time-sensitive, more people vote," said Al Cross, director of the University of Kentucky's Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues.

On the matter of rejected ballots, the news was mixed.

In the state's two biggest counties, Jefferson and Fayette (which includes Lexington), more than 15,000 absentee ballots were rejected. The most common reasons were the absence of a signature, a ballot's late arrival, or the envelope arriving unsealed.

That's a much larger number of rejected mail ballots than in a typical primary, but that's because the use of mail balloting was much more common this year. On a percentage basis, the likelihood of a mail ballot being rejected in Jefferson County was actually lower in the 2020 primary, at 4.43%, than it was in the 2018 and 2016 general elections, when the comparable rejection rates were 7.98% and 4.5%, respectively, the Courier-Journal reported. The rejection rate in Fayette County was higher, at about 8%.

Ultimately, the biggest impact of having a primarily mail election may have been in determining the winner of the Democratic primary to take on Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky. Former Marine fighter pilot Amy McGrath, the favorite of many establishment Democrats, was facing off against state Rep. Charles Booker, who received backing from many on the party’s left. McGrath, who is white, was the favorite until the race narrowed late in the contest, when Booker, who is Black, saw a surge in popularity.

McGrath ended up winning by about three percentage points, and political analysts said that some voters who mailed in votes for McGrath before Booker’s surge might have switched to Booker if they had gone to the polls on Election Day instead, potentially reversing the outcome. The intense public interest in the Senate primary and the 2020 election as a whole also provides a complicating factor when trying to gauge the unusually high turnout level, said D. Stephen Voss, a University of Kentucky political scientist.

Simply comparing the turnout in 2020 to that of the past few elections "is a false comparison, because political intensity has risen so much here, as elsewhere," Voss said.

Another dynamic at play in the primary was that the McGrath-Booker race took several days to call conclusively, which was attributed not just to the close race but also to the extra time it took to count the mailed ballots. That dynamic -- a delay of several days in announcing a winner -- could become common in this fall’s presidential and congressional races. (Read more about that here.)

After the overall turnout figures became clear, Adams, Kentucky’s secretary of state, urged Clinton to apologize for spreading "false information" prior to the primary. Clinton spokesman Nick Merrill told PolitiFact, "She has nothing to apologize for. What Republicans don’t understand is that the goal is to create as much safe access to the ballot box as possible so that Americans can exercise their fundamental rights."

Meanwhile, Seth Bringman, a spokesman for Fair Fight, the voting rights group founded by Abrams, disagreed that the high turnout totals disprove the notion that there was no voter suppression.

"A lot of people can overcome obstacles to vote, but the obstacles are still there and stop turnout from being even higher," Bringman said. "If a voter successfully votes but has to jump through hoops to get there, they have experienced voter suppression."

Overall, though, "I think the election was pretty successful," said Joshua A. Douglas, a University of Kentucky law professor who specializes in elections. "The national outcry over closed polling places was misinformed because it did not take into consideration the number of absentee ballot requests that had already gone out. There were never going to be 600,000 voters at one polling place in Louisville."

Some activists in Louisville told WKU Public Radio that mail voting isn’t sufficient for older Black voters, and that they should have greater access to in-person voting than they had during the primaries.

"Some of the seniors did not realize you have to have two signatures on there, so their votes didn’t get counted," said Sharon Horton, a member of the Voter Engagement Brigade.

An agreement between Adams and Beshear announced in mid-August significantly expands early in-person voting, as well as assuring that a voter's concern about coronavirus will count as a valid excuse for voting by mail. The state will also make a robust effort to contact voters whose ballot envelopes have technical errors, so they can fix them ahead of Election Day, or even after Election Day, as long as they were postmarked by Nov. 3 and arrive at an election office by Nov. 6. The number of in-person Election Day polling places remains to be worked out.

Former Kentucky Secretary of State Trey Grayson, a Republican, congratulated Adams, Beshear and the State Board of Elections on Twitter for "once again working across party lines to develop a well-thought-out plan for our November election. Proud of all involved."

Our Sources

Louisville Courier Journal, "Turnout among Black voters in Louisville rose in primary," July 12, 2020 (accessed via Nexis)

Louisville Courier Journal, "While national voices claim 'voter suppression,' Kentucky on pace for record voter turnout," June 22, 2020

Louisville Courier-Journal, "More than 15,000 primary absentee ballots rejected between Kentucky's two largest counties," July 7, 2020

Washington Post, "Kentucky braces for possible voting problems in Tuesday’s primary amid signs of high turnout," June 19, 2020

Lexington Herald-Leader, "Lexington voters find long lines and wait times as officials scurry to keep up," June 23, 2020

Lexington Herald-Leader, "Kentucky falls short of record turnout in primary defined by COVID-19 pandemic," June 30, 2020

WHAS-TV, "Kentucky Secretary of State calls on Hillary Clinton to apologize for 'false information' on primary," June 24, 2020

WFPL, "Ky. Secretary Of State Doesn’t Want Universal Mail-In Voting In November," July 28, 2020

WKU Public Radio, "Louisville Black Voter Group Calls For More Polling Places," Aug. 8, 2020

Hillary Clinton, tweet, June 22, 2020

Ava Duvernay, tweet, June 20, 2020

Stacey Abrams, tweet, June 20, 2020

LeBron James, tweet, June 20 2020

PolitiFact, "What’s happening with polling places in Kentucky?" June 23, 2020

Email interview with Nick Merrill, spokesman for Hillary Clinton, Aug. 11, 2020

Email interview with Seth Bringman, spokesman for Fair Fight, Aug. 11, 2020

Email interview with Laura Cullen Glasscock, editor and publisher of The Kentucky Gazette, Aug. 12, 2020

Email interview with Al Cross, director of the University of Kentucky's Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, Aug. 11, 2020

Email interview with Joshua A. Douglas, University of Kentucky law professor, Aug. 12 and Aug. 15, 2020

Email interview with D. Stephen Voss, University of Kentucky political scientist, Aug. 18, 2020