Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

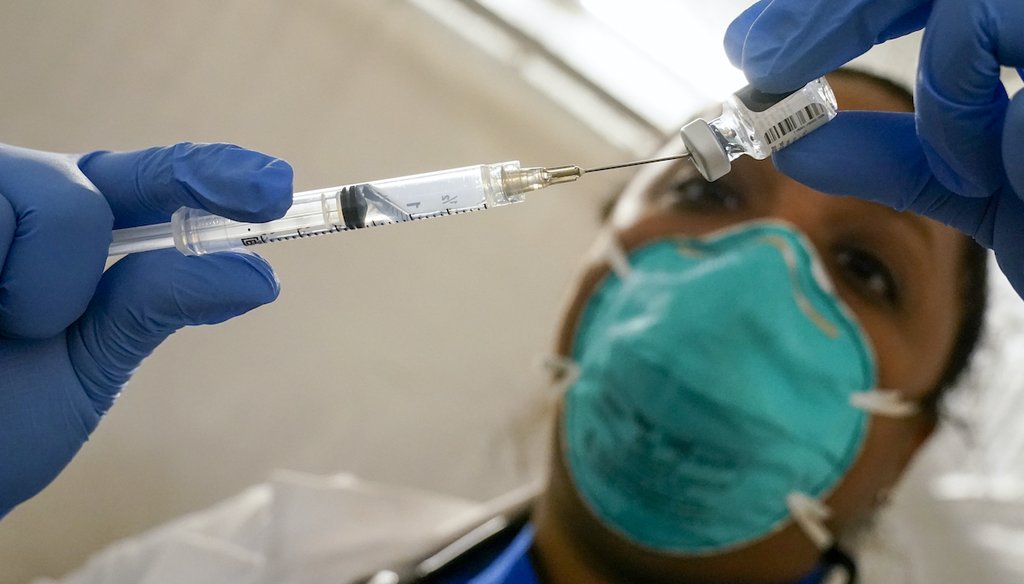

Dr. Yomaris Pena, internal medicine physician with Somos Community Care, extracts the last bit of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine out of a vial at a vaccination site in New York. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

There are currently three COVID-19 variants that concern scientists and public health officials.

-

The vaccines may be less effective against some variants, but scientists stressed that the shots still provide a significant public-health benefit.

-

Quick and widespread vaccine distribution — along with continued social distancing and mask-wearing — is key to stopping mutations from developing. Holding off on getting vaccinated will have the opposite effect, scientists say, and force everyone to live with the pandemic longer.

As officials scramble to successfully carry out a worldwide vaccination campaign against COVID-19, scientists are facing a new foe: Variants of the virus.

It’s not uncommon for a virus to change and evolve, and with uncontrolled spread in the United States and around the world, the coronavirus is getting plenty of chances. But it’s still happening faster than many researchers expected.

The new variants raise a number of questions. Will the vaccines still work? Is SARS-Cov-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, more contagious now? More deadly? What should people do to keep their families safe?

Here’s what we found out.

What’s the difference between a mutation, a variant and a strain?

A virus’ genetic code is written in molecules. As a virus spreads from person to person, it makes copies of itself and often misprints, causing a mutation in the code.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

"Most mutations are meaningless. They will have no real clinical implications," Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of Brown University’s School of Public Health, wrote on Twitter. "But every once in a while, a set of mutations will lead the virus to become more contagious, more lethal, or improve its ability to escape our vaccines."

The problematic mutations start to alter which amino acids — protein building blocks — a virus builds, eventually changing how the virus behaves. When this happens, it’s considered a variant.

If a virus goes on to change so much that our bodies can’t recognize it anymore, it can be considered a new strain. SARS-CoV-2, for example, is a mutated strain of coronavirus.

What are these COVID-19 variants we’re hearing about?

There are currently three COVID-19 variants that have captured the attention of scientists and public health officials so far.

The most widespread one, B117, was first detected in the United Kingdom in the fall of 2020. It’s considered more transmissible than the other variants currently circulating and may have an increased risk of death, but more research is needed.

B1351, which was first discovered in South Africa in October, and a similar variant named P1 that was identified in Brazil in early January are suspected of evading immunity in people who were vaccinated or previously infected. There is no current evidence that suggests these cause more severe disease, however.

All three have now been found in the U.S.

Will the vaccines work against them?

The vaccines may be less effective against some of the variants, but they will still provide a degree of protection unavailable to those who don’t take vaccines, researchers say.

There is evidence that suggests the current FDA-approved vaccines, as well as the Johnson & Johnson vaccine candidate, may pack less of a punch against some of the new variants, particularly B1351.

But experts stressed that just because the vaccine isn’t as potent, doesn’t mean the shots won’t provide a significant benefit.

"The polychromal response, which is what the vaccine elicits, is still effective. It's a little bit down but it’s not zero," said Dr. Benhur Lee, a professor of microbiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. "And, even if you get infected, you're still protected against severe COVID disease."

When Johnson & Johnson released its vaccine trial results on Jan. 29, some were deterred by the vaccine’s efficacy numbers: 72% in the U.S., 66% in Latin American countries, and 57% in South Africa.

But scientists say the results are still promising, and noted that the efficacy rates in Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccines that the public has grown accustomed to are extremely high compared with typical vaccines.

A good example is the flu vaccine, which in some years has only a 40%-50% efficacy rate and still manages to save millions of lives.

"You have to look at it from a public health standpoint," virologist Angela Rasmussen said during a COVID-19 vaccine panel hosted by the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas.

"All these vaccines are still showing better efficacy than that, and the flu vaccine does a very good job at preventing serious illness," she added. "Even though the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is not as efficacious at preventing symptomatic disease, it’s very effective at preventing serious disease. People need to be made aware of this."

Meanwhile, the variants have spurred vaccine makers to begin developing booster shots for later use that are reformulated to target the variants and heighten protection.

Once variants form, is there a way to help stop them?

Yes, by vaccinating lots of people — and doing so quickly.

Virus variants are not a new phenomenon. COVID-19 mutations have been emerging throughout the course of the pandemic. But the new variants show that the virus is changing faster than scientists initially anticipated.

Some experts believe their emergence may simply reflect a perplexing coronavirus strain. But others say that the virus’ unprecedented global spread is to blame: Every new infection gives a virus a chance to mutate, and when infections run wild, variants inevitably arise.

In a Feb. 1 White House briefing, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the country’s head infectious disease expert, stressed the importance of getting people vaccinated amid the variants.

"You need to get vaccinated when it becomes available as quickly and expeditiously as possible throughout the country," Fauci said. "Viruses cannot mutate if they don't replicate, and if you stop their replication by vaccinating widely and not giving the virus an open playing field … you will not get mutations."

Holding off on getting vaccinated because you think it’s a better route for protection will have the opposite effect, scientists say, and will end up exacerbating the problem and forcing everyone to live with the pandemic longer.

"Vaccinating on a population-wide level, you give the virus less chance to change more. Waiting is not the answer," said Lee, the microbiology professor. "Now is the time to ramp up the vaccination campaign. Not just in the U.S., but in other places, too. The virus does not need a visa to get around."

But vaccinations alone won’t do the trick.

The only way to get the virus under control for good is for the public to take other mitigation efforts seriously while vaccinations are underway, scientists say. This includes wearing masks, practicing social distancing and avoiding large crowds and unnecessary travel.

Our Sources

PolitiFact, 8 facts and 4 unknowns about the coronavirus vaccines, Dec. 17, 2021

PolitiFact, What we know about the new COVID-19 vaccine rollout strategy, Jan. 13, 2021

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, New Variants of the Virus that Causes COVID-19, Jan. 28, 2021

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US COVID-19 Cases Caused by Variants, updated Jan. 31, 2021

C-SPAN, White House COVID-19 Response Team Briefing, Feb. 1, 2021

New York Times, Which Covid Vaccine Should You Get? Experts Cite the Effect Against Severe Disease, Jan. 29, 2021

Oregon Public Broadcasting, What we know so far about new COVID-19 variants, Jan. 30, 2021

Twitter, Dr. Ashish Jha thread, Jan. 28, 2021

Modernatx.com, Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine Retains Neutralizing Activity Against Emerging Variants First Identified in the U.K. and the Republic of South Africa, Jan. 25, 2021

Science Magazine, Vaccine 2.0: Moderna and other companies plan tweaks that would protect against new coronavirus mutations, Jan. 26, 2021

Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, Covering the COVID-19 vaccine: What journalists need to know, Jan. 29, 2021

Phone interview, Dr. Benhur Lee, professor of microbiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Feb. 2, 2021