Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

Aliya Rahman is detained by federal agents on Jan. 13, 2026, near the scene where Renee Good was fatally shot by an ICE officer in Minneapolis. (AP)

Videos of confrontations between Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents and Minneapolis residents have flooded social media, showing some of the 3,000 officers who are deployed in the city stopping, questioning and detaining residents.

In one case, immigration agents escorted a U.S. citizen who is a grandfather of Hmong ancestry out of his house in his underwear in freezing weather. In another case, a father of a 5-year-old girl was briefly detained and zip-tied after he said a federal agent falsely accused him of not being a U.S. citizen because of his accent. The agency is also under scrutiny for reportedly dispatching a 5-year-old boy to knock on the front door of his home to lure relatives outside before agents then took the child into custody.

The events have sparked protests and prompted confusion over what ICE is legally allowed to do in public and private locations. Are there limits on when and how ICE can approach or detain you? Does the law differentiate between encounters in public versus a private space, such as a home? And is the Supreme Court becoming more tolerant of aggressive ICE actions?

Legal experts weighed in on the public’s constitutional protections from immigration stops and detentions.

What rights do people have when approached by ICE?

Federal law gives immigration agents the authority to arrest and detain people believed to have violated immigration law. But everyone — including immigrants suspected of being in the U.S. illegally — is protected against unreasonable searches and seizures under the Constitution's Fourth Amendment.

"All law enforcement officers, including ICE, are bound by the Constitution," said Alexandra Lopez, managing partner of a Chicago-based law firm specializing in immigration cases.

The Fourth Amendment doesn’t stop ICE from trying to deport people who have broken immigration law, but it has traditionally constrained the agency. The more extensive an enforcement action is, the higher the bar for immigration officers to justify their actions.

For example, officers can question someone in a public place, but more extensive interactions — such as a brief detention that’s not a formal arrest — require a "reasonable suspicion" that someone has committed a crime or is in the U.S. illegally, the Supreme Court has ruled.

Reasonable suspicion "has to be more than a guess or a presumption," said Michele Goodwin, a Georgetown University law professor. To meet this standard, a reasonable person would need to suspect that a crime was being committed, had been committed or would be committed.

Agents must meet an even higher bar to arrest someone. They need "probable cause," which generally requires enough evidence or information to suggest a person has committed a crime.

What is a "Kavanaugh stop"?

Historically, the Supreme Court has ruled that racial or ethnic profiling is unconstitutional. But a recent opinion by Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh gave ICE increased discretion to use race as a factor for stopping and questioning people.

In the 2025 case Noem v. Perdomo, Kavanaugh voted with a majority to stay a lower court ruling in favor of plaintiffs challenging federal immigration enforcement tactics in Los Angeles. Kavanaugh wrote that "apparent ethnicity" could be used as a "relevant factor" in determining reasonable suspicion, as long as it was combined with other factors and not used on its own.

Before Kavanaugh wrote this, courts had "often ruled that agents could not stop someone just because they ‘looked like an immigrant’ or were in a high-crime area," Lopez said. But if immigration officers follow Kavanaugh’s guidance, "it gives ICE a lot more discretion and justification to profile."

Critics of Kavanaugh’s opinion "argue that the ‘relevant factor’ language invites abuse, opening the door to ethnic profiling," said Rodney Smolla, a Vermont Law and Graduate School professor.

But Kavanaugh’s opinion was not co-signed by other justices, and it came from a procedural ruling rather than a substantive one, so its legal impact might be limited. The Supreme Court "has not made a definitive ruling on ‘Kavanaugh stops’ and their permissibility," said Ilya Somin, a George Mason University law professor.

Somin and other legal analysts have said Kavanaugh appeared to dial back his support for race or ethnicity as a factor when he wrote a different opinion several months later, in Trump v. Illinois, which stopped the Trump administration from deploying the National Guard in Illinois.

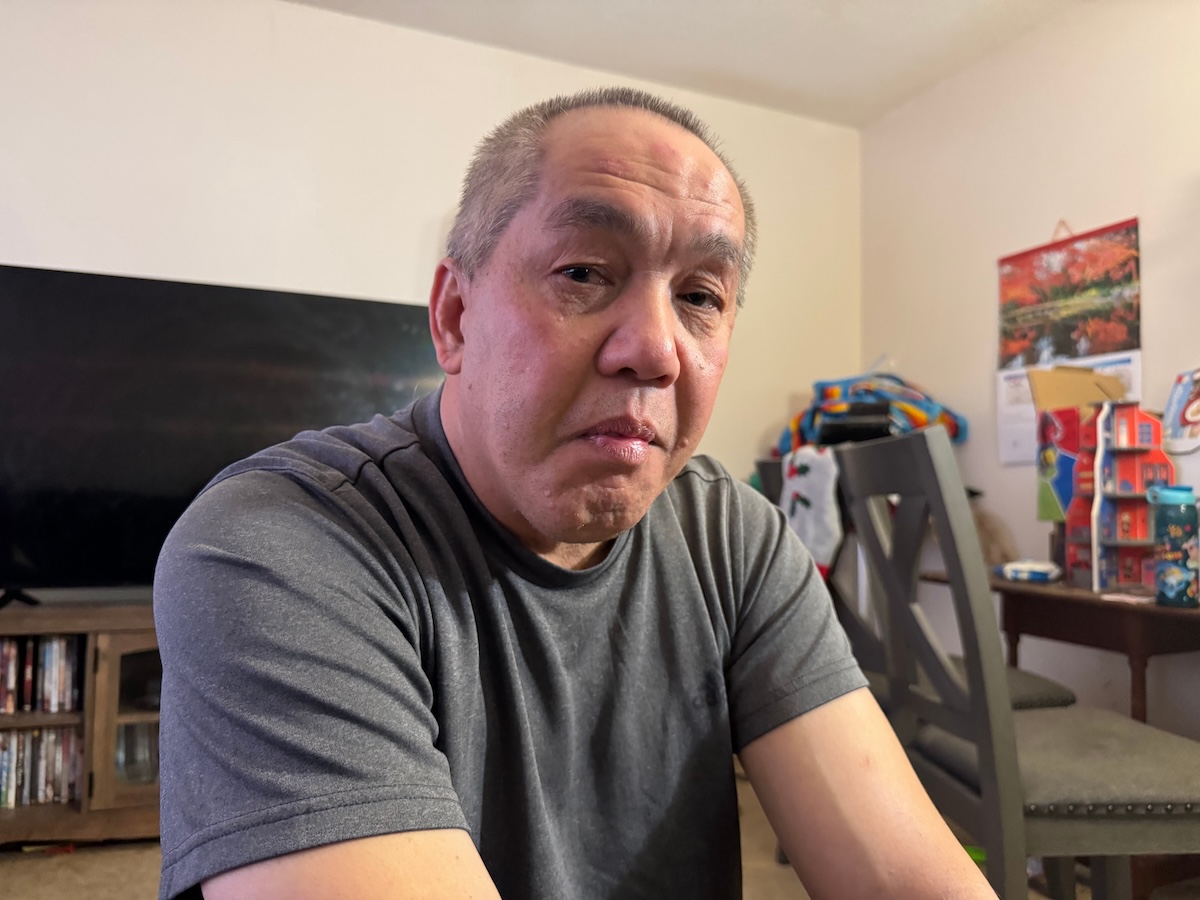

ChongLy (Scott) Thao, a U.S. citizen, at his home on Jan. 19, 2026, in St. Paul, Minn., the day after federal agents broke open his door and detained him without a warrant. (AP)

Do people’s rights differ inside their homes versus in a public space?

The Supreme Court has generally ruled that, unless a resident grants consent, law enforcement cannot enter a private home without a warrant signed by a judge, which requires the government to provide evidence showing probable cause.

"This means a person inside the house generally need not open the door, need not converse with the agent, and may require the agent to slip the warrant under the door or hold it to a window," Smolla said. There are some exceptions, such as if an officer encounters a violent crime in progress, or someone needing medical care.

Securing a judicial warrant is time consuming and is typically reserved for high-priority cases in which people are suspected of crimes beyond immigration violations, Lopez said. "It’s much easier for ICE to arrest individuals in public," she said.

In the past, federal immigration officers typically would not forcibly enter homes if they only had an administrative warrant issued by ICE itself, without a judge’s approval. Some lower courts have ruled in the past that entering homes without a judicial warrant violates the Fourth Amendment.

Specific ICE officials have authority to issue administrative warrants. The warrants require "probable cause to believe" that the person named in the warrant is subject to removal. But they are not reviewed by anyone in the judicial branch.

A leaked ICE memo approved entering homes without consent using an administrative warrant alone, as long as a final order of removal has been issued, The Associated Press reported Jan. 22.

The AP, citing a whistleblower disclosure, said the memo has been used to train new ICE officers, and "those still in training are being told to follow the memo’s guidance instead of written training materials that actually contradict the memo."

The May 12, 2025, memo, signed by ICE acting director Todd Lyons, said the Department of Homeland Security "has not historically relied on administrative warrants alone to arrest aliens subject to final orders of removal in their place of residence" but added that "the DHS Office of the General Counsel has recently determined that the U.S. Constitution, the Immigration and Nationality Act, and the immigration regulations do not prohibit relying on administrative warrants for this purpose."

If this policy were to be challenged in court, it’s unclear whether it would be ruled constitutional.

What can people do if they think ICE has infringed on their Fourth Amendment rights?

If you believe that your rights were violated, perhaps causing an injury or property loss, your options for suing for compensation are limited.

Unlike many state laws, federal law generally prohibits civil lawsuits against federal officials for violating people’s rights. A 1971 Supreme Court decision briefly loosened these prohibitions, before tightening them again.

Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California-Berkeley’s law school, and Burt Neuborne, a New York University emeritus law professor, wrote, "In one case, the Supreme Court held that people who had been illegally thrown off the Social Security disability rolls and were left without income could not sue, even though they had been given no due process. In another, the court declared that a man dying of cancer after the prison repeatedly denied him any medical care could not sue."

David Rudovsky, a University of Pennsylvania law professor, said there might be an opportunity to sue under a different law, the Federal Tort Claims Act.

Still, he said, plaintiffs would face a steep challenge: "It’s not an easy path, and most people can’t afford to retain a lawyer."

CLARIFICATION, Jan. 29, 2026: This story was updated to more accurately describe Kavanaugh's concurring opinion in the 2025 case Noem v. Perdomo.

Our Sources

Congressional Research Service, "Immigration Arrests in the Interior of the United States: A Primer," June 13, 2025

Congress.gov, "Overview of Unreasonable Searches and Seizures," accessed Jan. 22, 2026

Oyez, "Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Federal Bureau of Narcotics," 1971

U.S. Supreme Court, "Florida v. Royer," 1983

U.S. Supreme Court, "Noem v. Perdomo," 2025

U.S. Supreme Court, "Trump v. Illinois," 2025

U.S. Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, "Cotzojay v. Holder," 2013

U.S. Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit, "Lopez-Rodriguez v. Mukasey," 2008

Department of Homeland Security, sample arrest warrant, accessed Jan. 22, 2026

Legal Information Institute, definition of reasonable suspicion, accessed Jan. 22, 2026

Legal Information Institute, definition of probable cause, accessed Jan. 22, 2026

Bhavleen K. Sabharwal Law Office, "The Supreme Court Signals a Rolling Back of ICE’s Power to Arrest and Detain in Trump v. Illinois," Jan. 7, 2026

Erwin Chemerinsky and Burt Neuborne, "Renee Good’s Family Should Be Able to Sue the Officer Who Killed Her," Jan. 14, 2026

David French, "An Old Theory Helps Explain What Happened to Renee Good," Jan. 18, 2026

Vox.com, "How the Supreme Court paved the way for ICE’s lawlessness," June 24, 2025

Associated Press, "Immigration officers assert sweeping power to enter homes without a judge’s warrant, memo says," Jan. 21, 2026

Immigrations and Customs Enforcement, memo, May 12, 2025

CNN, "Federal agents’ aggressive moves in Minneapolis and St. Paul, visualized," Jan. 22, 2026

New York Times, "ICE Arrest of a Citizen, Barely Dressed, Sows Fear in Twin Cities," Jan. 21, 2026

Email interview with Cheryl Bader, Fordham University law professor, Jan. 21, 2026

Email interview with Rodney Smolla, law professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School, Jan. 20, 2025

Email interview with Ilya Somin, George Mason University law professor, Jan. 20, 2026

Email interview with Michele Goodwin, Georgetown University law professor, Jan. 20, 2026

Email interview with Alexandra Lopez, managing partner of the law firm Cunningham Lopez LLP, Jan. 20, 2026

Interview with David Rudovsky, University of Pennsylvania law professor, Jan. 21, 2026