Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

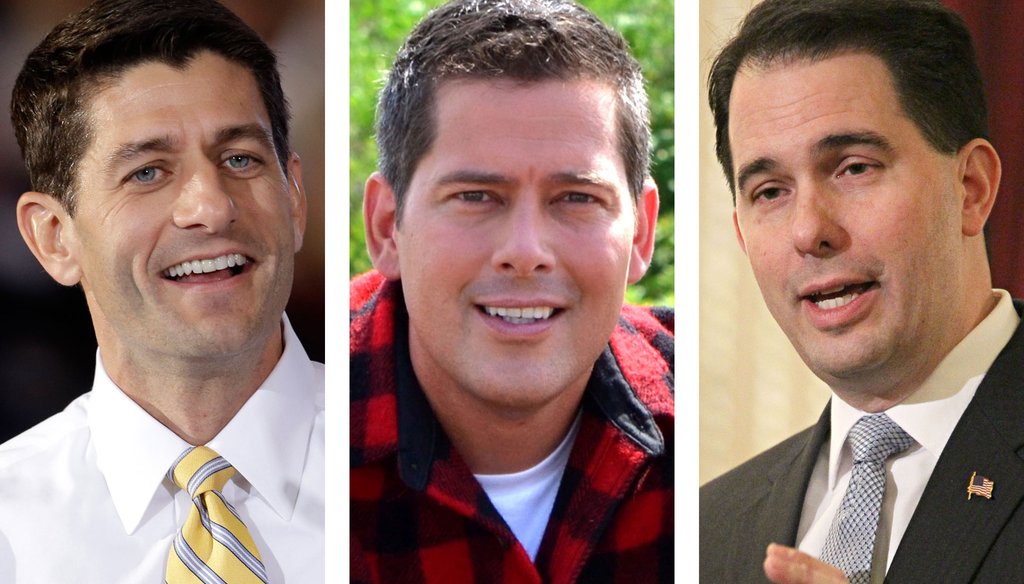

U.S. Reps. Paul Ryan and Sean Duffy, and Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker are all part of the immigration debate in the Republican Party.

If you do a computer search for "path to citizenship" and Paul Ryan or Sean Duffy or Scott Walker, you’ll see that at one time or another each has left the distinct impression they favored that opportunity for millions of immigrants living here illegally.

And you’ll also see that at times each has avoided the phrase or deflected questions about it when describing their views.

Welcome to the evolving vocabulary of the immigration debate in the Republican Party, in which one official’s "amnesty" is another’s "earned legalization," in which paths to citizenship can be "special" or "new" or "eventual," and "back of the line" describes both a punishment and a special privilege.

It’s a semantics game, largely, though important differences lie behind some of the words.

And the political stakes are high.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

Republicans supporting a path to citizenship are trying to broaden their party’s appeal, but risk alienating conservatives who oppose legalized status for those who jumped the legal waiting lines to come to America. And allowing citizenship for the undocumented is the most contentious issue of all, analysts say.

"Citizenship is a politically loaded phenomenon because it’s only citizens who can vote, and many believe that most of the undocumented are unofficial members of the Democratic Party," said Muzaffar Chishti, director of the New York University Law School office of the Migration Policy Institute, a research organization.

The sometimes-confusing political rhetoric comes as the issue draws to a head in the nation’s capital, with Democrats and Republicans working to find both consensus and political advantage.

It simplifies things to look at the possible changes in three distinct categories, Chishti said.

The first set of reforms under discussion entails legalizing the status of the undocumented -- at least temporarily -- instead of deporting them, as well as allowing them the right to work, and possibly travel abroad. There may be broad agreement in Congress on this step but some Americans, he said, see this as a form of amnesty.

A second level of reform is granting permanent residence through a green card. The third step is naturalization -- access to citizenship for immigrants.

Let’s take a look at those potential changes by examining the public statements of Ryan, Walker and Duffy.

Ryan’s hope

Attention has shifted to the Republican-controlled House -- and in particular to Ryan’s role as an active consensus-builder -- since the Senate’s 68-32 vote June 27 approving a complex immigration bill creating a 13-year path to citizenship for most of the 11 million unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. The measure would first implement tougher border security.

As Ryan, the GOP vice-presidential nominee in 2012, explores a 2016 presidential bid, he faces a delicate task -- and it shows in the way he talks about the issue.

Headlines have described Ryan’s support for an eventual "path to citizenship" for millions of immigrants living in the U.S. illegally. Democrats touted Ryan as a path to compromise. Ryan predicted the House would pass a path.

But we noticed that through all that Ryan rarely describes his own position as a "path to citizenship." He calls his position "earned legalization." And he argues most undocumented immigrants would be satisfied with legal status and would not take the next step to become naturalized citizens.

The audience matters.

Speaking July 23, 2013 to a conservative audience on Milwaukee talk radio, Ryan went so far as to call his position a "non-pathway to citizenship" and cast it in punitive terms, such as deferred adjudication. Still, he added that after a "probationary period," the undocumented could apply for citizenship "at the back of the line."

He was more open about his intentions at July 26, 2013 meeting with Hispanic constituents, confirming he supports a path to citizenship, though it would be a minimum of 15 years.

Ryan described his "path" to a Journal Sentinel reporter after the event.

"The thing we're saying is we don't want to give a person the ability to jump in front of the line. We're saying we want to have a person with probationary status to come out of the shadows to get right with the law," Ryan said. "And then after they have served those terms, and after they have a work visa, if they want to get in line like any other immigrant in America to get a green card, they can do that -- but only at the back of the line behind those people who have been legal all along."

Lynn Tramonte, deputy director of America’s Voice, which backed the Senate bill, said Ryan’s radio comments muddied his position somewhat but don’t appear to negate his earlier backing of a "path."

Ira Mehlman, spokesperson for the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), which opposed the bill, said Ryan’s view was "amnesty." Critics say the act of giving legal status to those who settled here without a sponsor and didn’t wait in line is amnesty, or a pardon.

"You broke the law, you stay here, you get rewarded for it," Mehlman said of a path to citizenship.

Duffy and Walker

Duffy, the second-term congressman from northern Wisconsin, is another Republican that pro-legalization forces hope might be there for their side in the end.

Duffy drew national media attention when he was quoted at a May town hall meeting in his district saying: "Most people come here to work. Most are Hispanics and work hard at tough jobs. We can’t send 11 million people back home. We should put them on a path to citizenship."

Then, after a July editorial board meeting with the Wausau Daily Herald, the headlines said he did not support citizenship for that group.

Duffy told the newspaper he endorsed "legal status" but said "legal status is not citizenship. Legal status is kind of like a work visa. You can stay in the country. You’re not going to be deported. You’re not going to be separated from your family. But also you’re not rewarded with citizenship. You don’t get a vote."

But Duffy added: "But you also get to stay here, and if you want to become a citizen, you can apply like anyone else around the world would apply."

Tramonte told us it’s hard to say where Duffy stands on a path. Duffy’s office did not respond to PolitiFact Wisconsin’s requests for clarification.

Mehlman, of FAIR, said Duffy’s position still sounded like he favored some form of amnesty.

Of Duffy and Ryan, Mehlman said: "Like a lot of Republicans they are looking to nuance amnesty; they want plausible deniability."

Finally, there’s Walker, another potential 2016 presidential candidate.

During the run-up to the Republican primary in his race for governor in 2010, Walker did an about-face on the Arizona law that requires police to ask people their immigration status if they suspect the person is in the country illegally.

First, he expressed serious concerns about racial profiling and other aspects of the law, but then endorsed the measure after getting a torrent of criticism on his Facebook page. Then in December 2012, as governor, Walker changed course again, saying he would fight to prevent an Arizona-style immigration bill from getting to his desk if lawmakers pursued it.

In early July 2013, Walker drew national notice when he told the Wausau editorial board "it makes sense" to allow citizenship to undocumented workers here given the right penalties and waiting periods.

But asked to confirm whether Walker was explicitly endorsing a "path to citizenship," Walker spokesman Tom Evenson told Politico and the Journal Sentinel he hasn’t endorsed a specific policy or bill.

Walker has pointedly ducked questions about his position on the Senate-passed bill, saying at a governors’ forum July 25, 2013: "I haven’t taken a position at all because I wasn’t elected to Congress."

What’s going on here?

"People just do not want to use the A-word, amnesty," said Chishti, of the Migration Policy Institute. "That was true in the 1986 (debate), but it’s much truer today. Now even ‘legalization’ has become sort of laden with risk. So people say ‘earned legalization.’ And now ‘pathway’ has become risky" in some circles.

"These are all politically charged words," he said, "and they have different meanings to different audiences."

Important distinctions

Behind the semantics are some critical nuances in the various approaches.

For example, there’s a lot of talk about "independent" or "new" or "special" pathways to citizenship for those here illegally.

Some say let the group become citizens through an "independent" path to it without having to find a sponsor and start over, Chishti notes. There is no such path in current law, but the Senate bill creates one -- though for most the path lasts 13 years.

Other officials say there should be no independent path for the undocumented, that they should get status only through current law: follow the normal procedures -- get a sponsor, file an application, and wait their turn.

And, some say, if the legislation allows the undocumented a new pathway to get legal residence, they should go to the "back of the line" -- by which they mean wait until the current long visa waiting lines are served first, Chishti said.

The Senate-passed bill creates a "special" or "independent" pathway, and has a "back of the line" aspect, too, Chishti said. It, however, seeks to speed up the wait times for current legal applicants so those at the back -- the undocumented -- won’t wait decades.

Current waits for some people from Mexico and the Philippines exceed 20 years, as we reported in rating Half True a claim by U.S. Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner.

He claimed that "it takes up to 25 years to obtain U.S. citizenship legally" in contrast to the Senate bill, which Sensenbrenner said would allow immigrants who came to the United States illegally to obtain citizenship in just 13 years.

We found he’s right for a large group of would-be Americans, but many others experience much shorter waits, and that Sensenbrenner omitted the fact that, going forward if the Senate bill became law, wait times are expected to drop.

Our Sources

Interview with Muzaffar Chishti, director, Migration Policy Institute office at NYU Law School, July 24, 2013

Interview with Ira Mehlman, spokesman, Federation for American Immigration Reform, July 25, 2013

Email exchange, Kevin C. Seifert, press secretary, Rep. Paul Ryan, July 23, 2013

Interview with Lynn Tramonte, deputy director at America’s Voice and America’s Voice Education Fund, July 22, 2013

Email exchange with Tom Evenson, press secretary, Gov. Scott Walker, July 23, 2013

Wausau Daily Herald, condensed transcript of Rep. Sean Duffy appearance, July 12, 2013

Charlie Sykes show podcast of appearance by Rep. Paul Ryan, July 23, 2013

Wausau Daily Herald Editorial Board, video clips from Gov. Scott Walker interview, July 2, 2013

ABC News, "What does ‘pathway to citizenship’ mean in immigration reform?" March 19, 2013