Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

The impeachment inquiry against President Donald Trump and nationwide voter suppression were center stage during the fifth Democratic presidential debate in Atlanta.

The debate, which was hosted by MSNBC and the Washington Post, opened with clashes over the candidates’ tax plans, pivoted to climate change records and ended with jabs over marijuana policy.

PolitiFact analyzed several statements from candidates on the debate stage at Tyler Perry Studios in Atlanta. Here are some highlights:

Health care issues take backseat | Proof lacking for voter suppression claims | Biden misstates African American support in Senate | Gabbard attacks Buttigieg's comments on Mexico | Steyer understates Congress’ action on climate change

Democratic presidential candidate former Vice President Joe Biden speaks during a Democratic presidential primary debate on Nov. 20, 2019, in Atlanta. (AP)

"160 million people like their private insurance."

— Former Vice President Joe Biden

This rates Half True.

A cursory look at polling would suggest that most of the people he’s talking about. Polling done earlier this year by the Kaiser Family Foundation with the Los Angeles Times found that most beneficiaries are "generally satisfied" with this insurance. (Kaiser Health News, a partner of PolitiFact, is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

But once you dig a little deeper, that narrative gets more complicated.

Even while Americans say they like their plans, large proportions indicate that the private coverage they have still leaves meaningful gaps, requiring them to skip or delay health care because they cannot afford it.

In the same KFF/L.A. Times poll, about 40% of people with employer-sponsored coverage said they had trouble paying medical bills, out-of-pocket costs or premiums. About half indicated going without or delaying health care because — even with this coverage — it was unaffordable. And about 17% reported making "difficult sacrifices" to pay for health care.

— Shefali Luthra, Kaiser Health News

Democratic presidential candidate Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, speaks during a Democratic presidential primary debate on Nov. 20, 2019, in Atlanta. (AP)

Says Pete Buttigieg said that as president, he "would be willing to send our troops to Mexico to fight the cartels."

— Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii

Gabbard’s attack contained an element of truth, but was exaggerated and misleading.

Buttigieg, who did a seven-month deployment as a Navy Reserve intelligence officer in Afghanistan, said Gabbard took his remarks out of context.

Gabbard, a major in the Army National Guard who served two tours of duty in the Middle East, alluded to comments Buttigieg made three days earlier in a candidate forum in Los Angeles. An interviewer said President Donald Trump had suggested sending U.S. troops to Mexico to help deal with the drug cartels there, then had this exchange with Buttigieg:

Question: "Do you see a time where troops could go into Mexico if Mexico welcomed it?"

Buttigieg: "There is a scenario where we could have security cooperation as we do with countries around the world. Now, I would only order American troops into conflict if there were no other choice, if American lives were on the line and if this were necessary in order for us to uphold our treaty obligations. But we could absolutely be in some kind of partnership role if and only if it is welcomed by our partner south of the border."

His campaign later clarified, the Sacramento Bee reported, that Buttigieg would only be open to military use as a "last resort" in response to Mexican cartel violence or an outside threat that endangers the country’s security.

— Tom Kertscher

"While I was passing the first climate change bill that PolitiFact said was a game-changer, … my friend (Steyer) was introducing more coal mines and produced more coal around the world, according to the press, than all of Great Britain produces."

— Former Vice President Joe Biden

Biden was one of the first lawmakers to introduce a climate change bill. But we here at PolitiFact didn’t call it a "game-changer."

Biden’s shout-out to PolitiFact came in response to a comment from billionaire Tom Steyer. Steyer said that he is the only Democratic candidate who has made climate change his No. 1 priority.

We found that Biden was one of the first U.S. legislators to introduce a climate change bill.

His first climate change bill was introduced in 1986, but it died in the Senate. The next year, a version of Biden’s legislation became an amendment to a State Department funding bill. President Ronald Reagan signed it into law.

Biden’s Global Climate Protection Act called on the president to set up a task force to plan how to mitigate global warming. It also called on the president to make climate change a higher priority item on the U.S.-Soviet agenda.

While Congress had focused on the issue before, most experts we spoke to said Biden’s bill was the first climate change legislation of its kind. However, those same experts also cautioned against overstating the importance of the bill. It didn’t introduce a plan for reducing emissions or adapting infrastructure for climate change.

"It was a plan to make a plan. Which, of course, neither Reagan nor Bush ultimately did," Josh Howe, a professor of history and environmental studies at Reed College, previously told PolitiFact.

As for Steyer’s own record on the environment, a 2014 report from the New York Times analyzed the operations of Farallon Capital Management, Steyer’s investment management company. It found that Farallon invested millions of dollars in companies that operate coal mines or coal-fired power plants.

The Times reported that Farallon-supported coal mining companies increased their annual production by about 70 million tons after they received money from the fund. "That is more than the amount of coal consumed annually by Britain," the Times wrote.

— Daniel Funke

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., speaks as Democratic presidential candidate Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, listens during a Democratic presidential primary debate on Nov. 20, 2019, in Atlanta. (AP)

"The wealth tax: I’m sorry, it’s cumbersome. It’s been tried by other nations. It’s hard to evaluate."

— Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J.

It’s accurate to say that other countries have tried wealth taxes similar to the one that Warren has proposed. Several countries still have them.

He was responding to Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax, which would put a 2% levy on wealth above the $50 million mark to provide universal pre-kindergarten and cancel student debt for most people. (We previously found there’s ample reason to doubt her math.)

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, an international body based in Paris, has counted 12 or 13 countries that collected revenues from net wealth taxes in 1996. (The tally differs slightly based on how you measure it.)

Nine European countries have ended their wealth taxes since then. Today, six or seven European nations have some form of wealth tax.

As Booker said, the reason why some countries nixed their wealth taxes has to do with how difficult it is to levy them. A 2015 report from the European Commission found that determining the value of people’s assets was difficult. A 2018 report from the OECD said revenues collected from wealth taxes were generally low and that there were several "efficiency and administrative concerns."

However, we’ve spoken to experts who say the same thing wouldn’t necessarily happen in the United States. OECD analysts said arguments for and against wealth taxes depend on how other tax laws would work with Warren’s proposal.

— Daniel Funke

Says he has the backing of "the only African American woman that’s ever been elected to the United States Senate."

— Former Vice President Joe Biden

This was a slip-up that Biden quickly corrected after a mystified reaction from other candidates on the stage — notably Kamala Harris, who is an African American woman elected to the Senate and who, as an active candidate, has not endorsed Biden.

"That's not true!" said Booker.

"I'm right here!" said Harris, laughing.

Biden was referring to his endorsement by Carol Moseley Braun, a Democrat who represented Illinois in the Senate for one term. She was the first African American woman to be elected to a Senate seat. Harris was the second and, so far, only other to achieve that distinction.

— Louis Jacobson

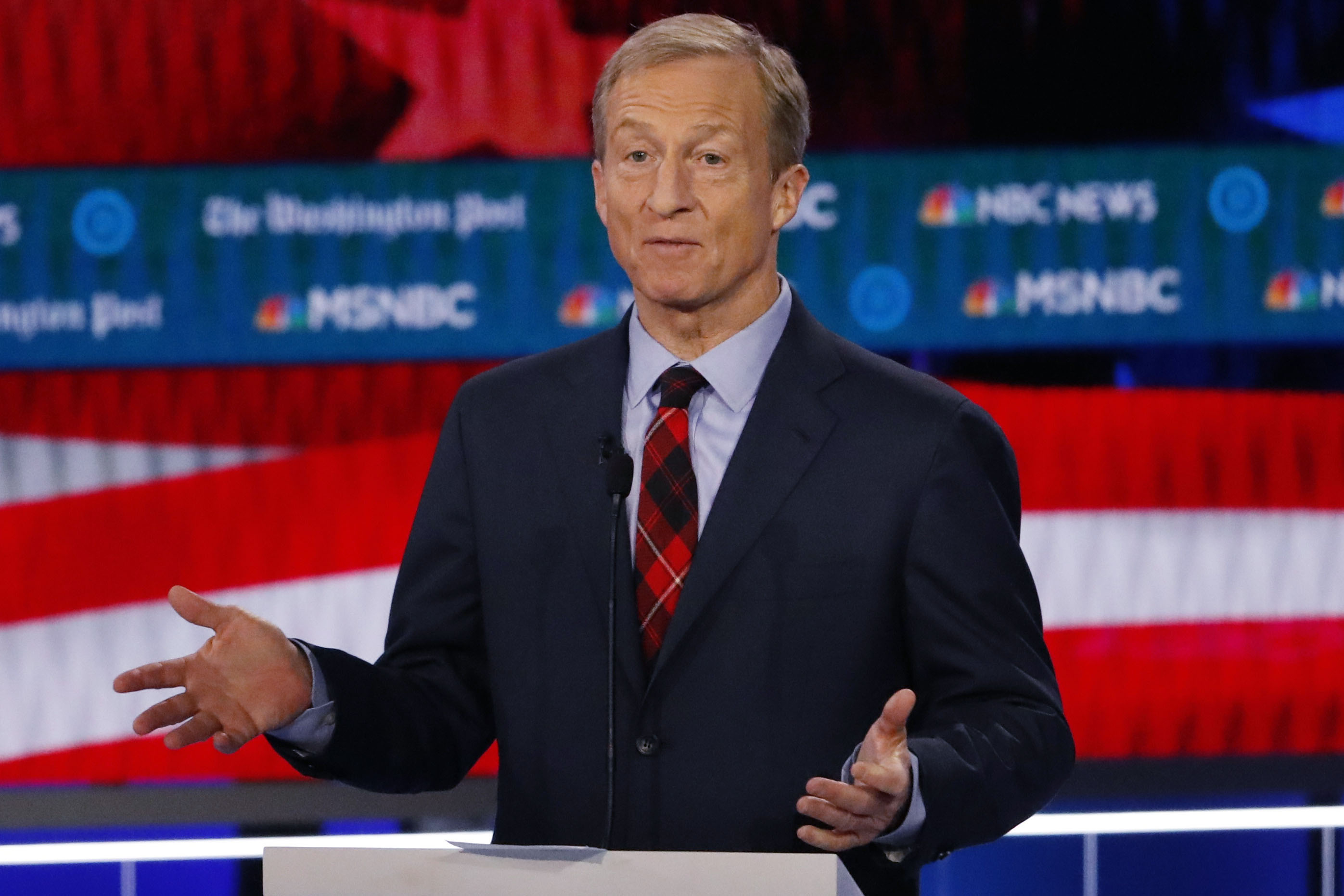

Democratic presidential candidate investor Tom Steyer speaks during a Democratic presidential primary debate on Nov. 20, 2019, in Atlanta. (AP)

"Congress has never passed an important climate bill, ever."

— Tom Steyer, hedge fund manager

While reasonable people can disagree about what qualifies as "important," Congress has certainly passed several notable bills responding to climate change over the years.

One landmark law that passed well before the modern era of climate change policy — the Clean Air Act 1963 — paved the way for the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, which used regulatory mechanisms to set state carbon emissions targets and a pathway to meet those targets. The Trump administration shelved the plan before it went into effect.

In 1992, the Senate passed the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, which had been signed under President George H.W. Bush and which laid out an international process for future climate-change agreements.

That same year, language creating the renewable energy production tax credit was signed into law as part of the Energy Policy Act. This credit gave a boost to wind energy and, starting in 2005, solar energy. The tax credit is widely seen as enabling the United States’ fast-growing renewable-energy sector.

In 2007, President George W. Bush signed the Energy Independence and Security Act, which established a renewable fuel standard for fuel producers, offered incentives for renewable fuel production, and phased out incandescent light bulbs.

And in the same year, an appropriations bill established mandatory reporting of large-source greenhouse gas emissions.

— Louis Jacobson

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., center speaks during a Democratic presidential primary debate on Nov. 20, 2019, in Atlanta. (AP)

"We still have 11 states that don’t have back-up paper ballots."

— Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn.

Klobuchar would have been better off saying some counties and towns in 11 states don’t offer back-up paper ballots, according to research by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University, a liberal organization that advocates for voting rights.

An August report from the group concluded that "11 states use paperless machines as their primary polling place equipment in at least some counties and towns, as Virginia, Arkansas, and Delaware transitioned to paper-based voting equipment in 2017, 2018, and 2019."

Three of those states — Georgia, South Carolina and Pennsylvania — have committed to replacing equipment by 2020. That means that in 2020, portions of eight states will still use paperless equipment. Louisiana would be the only state to have paperless voting systems statewide, Liz Howard, counsel for the Brennan Center's Democracy Program, told PolitiFact.

The Senate Intelligence Committee’s report on Russian interference in July found that "paper ballots and optical scanners are the least vulnerable to cyber attack; at minimum, any machine purchased going forward should have a voter-verified paper trail and remove (or render inert) any wireless networking capability."

— Amy Sherman

Our Sources

See fact-checks.