Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

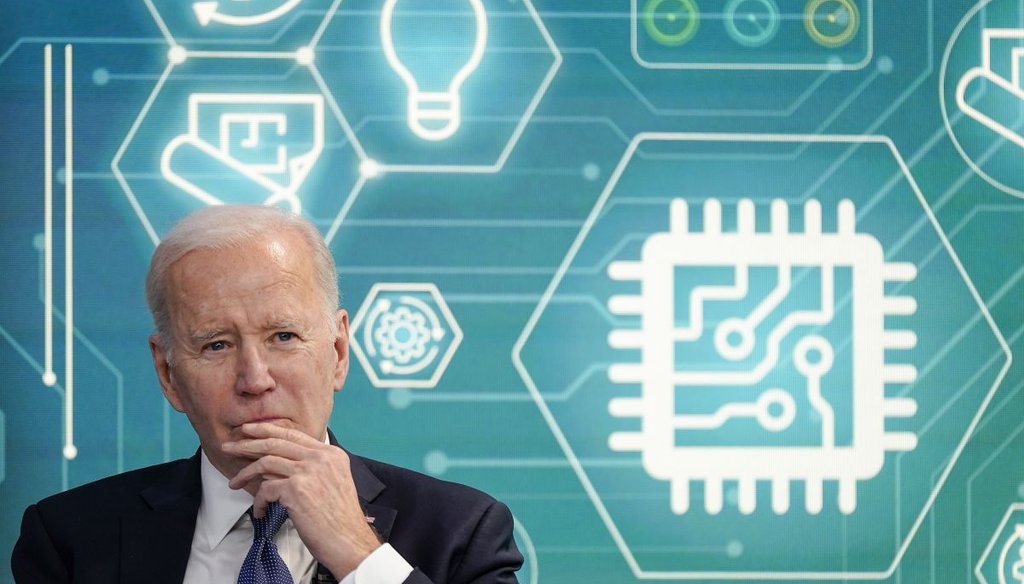

President Joe Biden attends an event to support legislation that would encourage domestic manufacturing and strengthen supply chains for computer chips in Washington on March 9, 2022. (AP)

If Your Time is short

• Manufacturing jobs have increased under President Joe Biden. But the increase began under his predecessor, Donald Trump, and is because of policies enacted by both of them.

• Despite the recent gains, the number of manufacturing jobs has declined by about one-third since 1979, while the workforce as a whole has increased by 57%. Automation and globalization are key reasons why manufacturing now makes up a smaller piece of the jobs pie.

• Experts do not expect the U.S. manufacturing employment level to reach its levels from the 1950s to the 1970s, given today’s far different international economic landscape.

President Joe Biden frequently talks about a significant uptick in manufacturing jobs on his watch.

It’s a message designed to play well in the industrial Midwest, where states like Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are hosting a mix of competitive Senate and gubernatorial races in the midterm elections. Biden also seeks to paint his record as superior to that of his presidential predecessor, Donald Trump.

"On Trump’s watch, American manufacturing was hollowed out. On my watch, ‘Made in America’ isn’t just a slogan, it’s a reality," Biden said in remarks Oct. 24 at the Democratic National Committee headquarters.

Three days later, Biden traveled to Syracuse, New York, to spotlight plans by Micron to invest in microchip manufacturing. "This country lost over 180,000 manufacturing jobs under the last guy that had this job," Biden said at an event there. "We’ve created 700,000 manufacturing jobs on my watch, adding manufacturing jobs at a faster rate than in 40 years."

On the job statistics, Biden is numerically correct. However, experts say he should use more caution on his victory lap — that comparison between Trump and Biden is murkier than the president is letting on.

We asked the White House for evidence to back up the idea that Biden has been unusually successful in creating manufacturing jobs. Officials pointed to data showing that it took 30 months — from April 2020 to September 2022 — for manufacturing jobs to return to their pre-pandemic recession peak. That may sound like a long time, but after the recessions that struck in 1990, 2001 and 2007, manufacturing jobs never even bounced back to their prior level after 100 months.

The White House also pointed to two bipartisan bills Biden signed in his first two years in office — an infrastructure measure and one designed to bolster chip manufacturing and science research. And it touted the Democratic-only passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, which offers incentives for purchases of clean energy technology.

President Joe Biden speaks with Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger at the groundbreaking of a new Intel semiconductor manufacturing facility in New Albany, Ohio, on Sep. 9, 2022. (AP)

Scott Paul, president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing, gives Biden some credit for the manufacturing job gains.

Biden has created "a climate for factory investment that we haven’t seen for generations," including the investments in infrastructure, clean energy manufacturing and semiconductors, Paul told PolitiFact. These are "already paying dividends. You can see from the ubiquitous factory announcements almost every week."

Gary Burtless, an economist at the Brookings Institution, a research and policy center in Washington, D.C., agreed that the gain in about 700,000 manufacturing jobs since the pandemic-era low has been unusually rapid. He said this was enabled by some things that a president can control, notably the federal pandemic aid programs for businesses, unemployed workers and Americans who received stimulus checks. Collectively, such policies kept consumer demand for manufactured goods strong.

But the pandemic relief bills began under Trump, as did the numerical rise in manufacturing jobs.

"The recovery trends are evident during both the Trump and Biden administrations," Burtless said. "We can quibble about whether the trends are a bit stronger in the Biden administration, but certainly the recovery of U.S. manufacturing was already plain in the Trump administration."

Other factors encouraged the manufacturing jobs recovery and were clearly beyond Biden’s control, such as international trade disruptions caused by the pandemic.

"U.S. manufacturers may have faced less overseas competition than they would have faced without the pandemic, giving them reason to boost employment," Burtless said.

Ultimately, the Biden administration’s policies and triumphant rhetoric on manufacturing are hardly new, said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the center-right American Action Forum. "Lots of presidents have said similar things about their predecessor," he said. "We’ve seen all of these (policy) levers pulled before."

One area that Biden’s message doesn’t address: The recent manufacturing job gains leave employment well below historical highs.

Since peaking in 1979, manufacturing job numbers have fallen by just more than one-third, even as the overall number of available workers in all U.S. sectors has grown by 57% during the same period.

Experts say the biggest factors in the shrinking of U.S. manufacturing employment are automation and globalization.

"There is incredible automation in manufacturing," said Allan Collard-Wexler, a Duke University economist. "The only manufacturing sector that built plants with over 2,500 workers on a regular basis in the U.S, in the last 30 years are meatpacking plants, an industry where the irregular patterns of animal biology make it difficult to automate."

Automation has produced sharp gains in efficiency, compounding over several decades. Even as manufacturing employment has declined by one-third since 1979, industrial production for the manufacturing sector has more than doubled.

As for globalization, "firms have offshored some of their production," said Teresa Fort, an associate professor of business administration at Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business. Also, she said, "foreign firms in lower-wage countries can produce some goods more cheaply."

Manufacturing jobs are alluring to politicians partly because, historically, they pay better than many other types of jobs — especially for people with moderate levels of educational attainment.

Experts said that Biden’s policies, including support for chip making, could have a positive impact. Fort said moving to reduce or eliminate tariffs on inputs that are driving up costs for U.S. manufacturing companies could also help.

Still, even if Biden’s policies do continue to produce gains in manufacturing jobs in the coming years, experts aren’t bullish about U.S. manufacturing returning to its glory days.

"We’ve had this recurring mantra to promote U.S. manufacturing, but the reality is that if you go back to the 1950s or 1960s, the U.S. was essentially a global manufacturing colossus astride a world devastated from World War II," Holtz-Eakin said. That’s not the case today, by any stretch.

The scale of a U.S. manufacturing comeback, Fort said, will depend on how well U.S. companies are able to compete with other countries’ manufacturing sectors.

Meanwhile, not everyone is convinced that the manufacturing sector merits the intense focus placed on it by Biden, or by his predecessors.

"What’s so special about manufacturing jobs?" Holtz-Eakin said. "We are good at inventing things. When you have higher value-added items, you shed lower value-added items."

Our Sources

Joe Biden, remarks at the Democratic National Committee headquarters, Oct. 24, 2022.

Joe Biden, remarks in Syracuse, N.Y., Oct. 27, 2022

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, manufacturing jobs, accessed Nov. 1, 2022

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, civilian labor force level, accessed Nov. 1, 2022

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, industrial production index, accessed Nov. 1, 2022

Email interview with Gary Burtless, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, Oct. 27, 2022

Email interview with Allan Collard-Wexler, Duke University economist, Oct. 27, 2022

Email interview with Teresa Fort, associate professor of business administration at Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business, Oct. 27, 2022

Interview with Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum, Oct. 28, 2022