Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

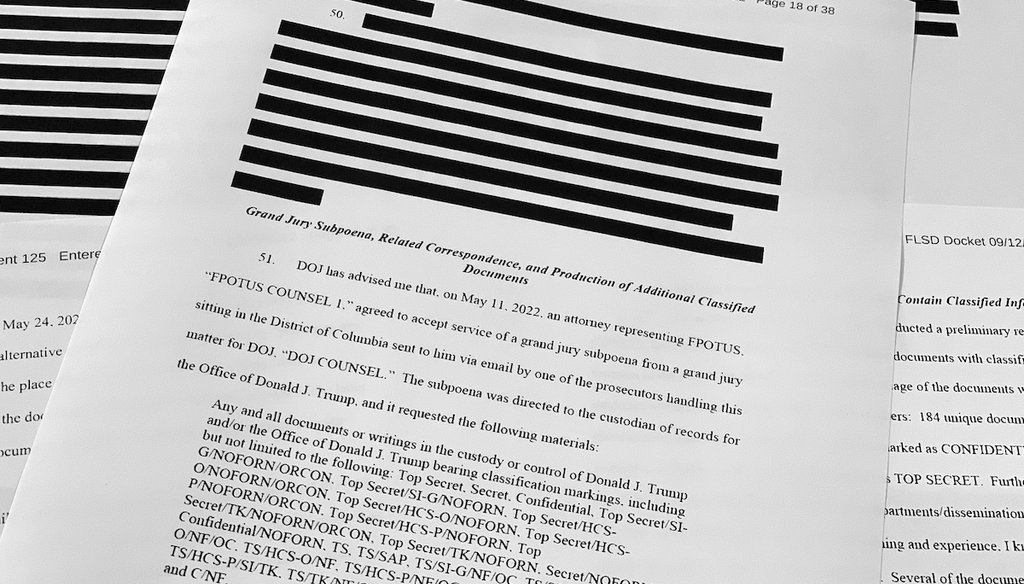

Pages from the FBI affidavit laying out the basis for a search warrant for former President Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago estate. (AP)

If Your Time is short

• Presidents have an unusual degree of authority to declassify documents. But there’s legal precedent that counters Trump’s assertion on Fox News that he can “declassify just by saying it's declassified.”

• In multiple legal cases during the Trump presidency, courts rejected the idea that a president can declassify simply by tweeting or issuing a news release and not following up through more formalized processes involving executive agencies.

Former President Donald Trump attracted wide attention for his comments about presidential declassification powers in an interview with Fox News’ Sean Hannity.

Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home was searched in August by federal agents who were looking for documents the government believes he may have taken improperly when he left the presidency. At least some of these documents were classified.

In the Sept. 21 interview with Hannity, Trump indicated that there should be no concern about taking classified documents to Mar-a-Lago. He said that’s because when he was president, he had the power to declassify documents at will — without having to document that decision or go through any formal steps to coordinate with executive branch agencies.

Here’s the exchange:

Hannity: "OK, you have said on Truth Social a number of times you did declassify —"

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

Trump: "I did declassify."

Hannity: "OK. Is there a process? What was your process to declassify?

Trump: "There doesn't have to be a process, as I understand it. You know, there's — different people say different things, but as I understand there doesn't have to be. If you're the president of the United States, you can declassify just by saying it's declassified. Even by thinking about it, because you're sending it to Mar-a-Lago or to wherever you're sending it. And there doesn't have to be a process. There can be a process, but there doesn't have to be. You're the president, you make that decision. So when you send it, it's declassified. I declassified everything."

We have previously written about legal experts’ dim view of the legality of what might be called "in-brain" presidential declassification.

Already, a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit has ruled that there was "no evidence" that any of the documents sought at Mar-a-Lago "were declassified," and that Trump’s lawyers have "resisted providing any evidence that he had declassified any of these documents." They also wrote that the entire declassification issue is "a red herring" because other laws, including the Presidential Records Act, mandated that he return all government documents, whether classified or not, once he left office.

We found at least three earlier court cases that back up the notion that in-brain declassification is unlikely to pass judicial muster.

Each of these three cases involved instances in which Trump or the White House issued something tangible, such as a tweet or a news release, that discussed declassification. By contrast, Trump told Hannity that he could essentially declassify in his head without any documentation at all — an action even less tangible that what multiple courts have already rejected.

It’s impossible to know how any court will rule in the future, but legal experts said these three cases collectively provide a strong argument against the powers Trump claimed to Hannity.

The president’s declassification powers are broad

Trump has a point that presidents have an unusual degree of authority to declassify documents.

The president, as commander in chief, is ultimately responsible for classification and declassification. When people lower in the chain of command handle classification and declassification duties — which is usually how it’s done — it’s because they have been delegated to do so by the president directly, or by an appointee chosen by the president.

The majority ruling in the 1988 Supreme Court case Department of Navy v. Egan — which involved the legal recourse of a Navy employee who had been denied a security clearance — addresses this line of authority.

"The president, after all, is the ‘Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States’" according to Article II of the Constitution, the court’s majority wrote. "His authority to classify and control access to information bearing on national security ... flows primarily from this constitutional investment of power in the president, and exists quite apart from any explicit congressional grant."

Steven Aftergood, director of the Federation of American Scientists Project on Government Secrecy, told PolitiFact in 2017 that such authority gives the president the authority to "classify and declassify at will."

The official documents governing classification and declassification stem from presidential executive orders. But even these executive orders aren’t necessarily binding on a president. The president is not "obliged to follow any procedures other than those that he himself has prescribed," Aftergood said. "And he can change those."

The situation recalls President Richard Nixon’s infamous comment, "When the president does it, that means that it is not illegal." But national security specialists at the blog Lawfare wrote that this "is actually true about some things. Classified information is one of them. The nature of the system is that the president gets to disclose what he wants."

Do the president’s powers extend to in-brain declassification?

Could Trump have a legal basis for arguing that he declassified certain documents in private while president? That’s not how the system is designed to work, experts said.

"Merely proclaiming a document or group of documents declassified and doing nothing more would not suffice," Bradley Moss, a Washington, D.C.-based lawyer who works on national security cases, told PolitiFact in August.

Follow-through is required.

"He had to identify the specific documents he was declassifying, he needed to memorialize the order in writing for bureaucratic and historical purposes, and he needed to have staff physically modify the classification markings on the documents themselves," Moss said. "Until that was done, the documents, per the security classification procedures, still have to be handled, transmitted and stored as if they were classified."

Three cases suggest Trump’s argument could be challenged

Three cases speak directly to the limits of presidential declassification powers. Each of them involved Trump, and none support Trump’s assertion to Hannity.

One case is James Madison Project v. U.S. Department of Justice. The case involved media outlets suing to secure an unredacted version of Justice Department applications to surveil Carter Page, a onetime Trump associate who later came under scrutiny in special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation of alleged Trump ties to Russia.

The Justice Department argued that some parts of the application were classified and could not be released under the Freedom of Information Act. The news organizations contended that a September 2018 press release from then-White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said Trump had "directed" the declassification of the Page warrants.

In his decision rejecting the media outlets’ right to the unredacted document, U.S. District Judge Amit P. Mehta concluded that a White House "press release was not a declassification order."

A second case is New York Times and Matthew Rosenberg v. Central Intelligence Agency. In this case, the Times, using a Freedom of Information Act request, sought acknowledgment and documents from the CIA about the existence of a covert program for arming and training rebel forces in Syria.

The CIA issued a statement saying it could neither confirm nor deny the existence of relevant records. The Times countered that in a tweet and an interview with The Wall Street Journal, Trump had broached the existence of such a program and thus effectively rendered the program’s secrecy moot.

After the trial court sided with the CIA, the Times appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit. Two of the judges on a three-judge panel upheld the lower court’s ruling.

The majority ruled that despite the president’s tweets, "declassification cannot occur unless designated officials follow specified procedures. Moreover, courts cannot ‘simply assume, over the well-documented and specific affidavits of the CIA to the contrary,’ that disclosure is required simply because the information has already been made public."

The third case, Leopold v. Department of Justice, also undercuts what Trump asserted to Hannity.

Jason Leopold, then a journalist with BuzzFeed, brought a Freedom of Information Act case seeking documents related to Mueller’s investigation. In seeking an expedited review of redactions before the 2020 presidential election, the plaintiffs cited a series of Trump tweets in which he said he had declassified all documents related to Mueller’s investigation. One tweet on Oct. 6, 2020, said, "I have fully authorized the total Declassification of any & all documents pertaining to the single greatest political CRIME in American History, the Russia Hoax. Likewise, the Hillary Clinton Email Scandal. No redactions!"

The government countered that the tweets were not "self-executing," meaning that they did not amount to a formal declassification order. District Court Judge Reggie Walton ordered the Justice Department to secure a declaration from Trump or a close associate about what his intent was in sending those tweets.

Then-Chief of Staff Mark Meadows submitted a sworn declaration in which he said, "The president indicated to me that his statements on Twitter were not self-executing declassification orders and do not require the declassification or release of any particular documents."

After receiving Meadows’ testimony, Walton denied Leopold’s request for an expedited review of the redactions.

RELATED: Could Trump argue he declassified the documents found in the Mar-a-Lago search?

Our Sources

Donald Trump, interview with Sean Hannity, Sept. 21, 2022 (accessed via Nexis)

James Madison Project v. U.S. Department of Justice

New York Times and Matthew Rosenberg v. Central Intelligence Agency

Leopold v. Department of Justice

Department of the Navy v. Egan, 484 U.S. 518 (1988)

Lawfare, "Bombshell: Initial thoughts on The Washington Post’s game-changing story," May 15, 2017

Just Security, "Expert explainer: Criminal statutes that could apply to Trump’s retention of government documents," Aug. 9, 2022

The Hill, "Meadows says Trump did not order declassification of Russia documents," Oct. 20, 2020

Politico, "DOJ: Trump's 'total declassification' of Russiagate docs has no effect," Oct. 13, 2020

Talking Points Memo, "Judge: Trump said he’d declassify Russia probe docs but never actually did," March 3, 2020

The New York Times, "Trump claims he declassified documents. Why don’t his lawyers say so in court?" Sept. 22, 2022

PolitiFact, "Does the president have 'the ability to declassify anything at any time?'" May 16, 2017

PolitiFact, "Have people been prosecuted for mishandling White House records?" Aug. 10, 2022

PolitiFact, "Could Trump argue he declassified the documents found in the Mar-a-Lago search?" Aug. 11, 2022

Email interview with John Pike, director of globalsecurity.org, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Robert F. Turner, associate director of the University of Virginia's Center for National Security Law, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Stephen I. Vladeck, professor at the University of Texas School of Law, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Elizabeth Goitein, co-director of the Liberty & National Security Program at NYU’s Brennan Center, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Steven Aftergood, director of the Federation of American Scientists Project on Government Secrecy, Aug. 11, 2022

Email interview with Thomas S. Blanton, director of the National Security Archive at George Washington University, Aug. 10, 2022

Interview with Matt Topic, partner at the law firm Loevy & Loevy, Sept. 22, 2022

Email interview with Bradley Moss, partner with the law firm Mark S. Zaid P.C., Sept 22, 2022