Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

A man holds a poster near the courthouse in New York City on March 20, 2023. (AP)

Former President Donald Trump recently warned his followers that he "will be arrested" in the coming days. Although nothing has yet been confirmed, he referred to the Manhattan district attorney’s office, which has been investigating crimes related to hush payments to adult entertainment star Stormy Daniels.

Reporting initially published by The New York Times suggested that Manhattan District Attorney Alvin L. Bragg is close to filing charges for the alleged concealment of a $130,000 hush money payment to Daniels by Michael Cohen, Trump's then-lawyer, shortly before the 2016 presidential election.

Because criminal charges against a former president would be historically unprecedented, we asked legal experts a few questions that might be atop Americans’ minds. They agreed that criminal charges would not prevent Trump from running for president, and likely wouldn’t pose logistical hurdles for his campaign. They also walked us through what was likely to happen if and when he is taken into custody in New York City.

Long story short, Trump could continue running for president, just as he has been.

"There is no bar to running for president while under indictment and nothing that would prevent his serving as president," said Stanley Brand, a longtime election law expert who is now a distinguished fellow in law and government at Penn State Dickinson Law.

The U.S. Constitution upholds the principle that voters decide who shall represent them, and its qualifications are limited to natural-born citizenship, age (35 by Inauguration Day) and residency in the United States (14 years).

Convicted felons have run for president in the past. Lyndon LaRouche was convicted in 1988 of tax and mail fraud conspiracy and ran for president multiple times between 1976 and 2004.

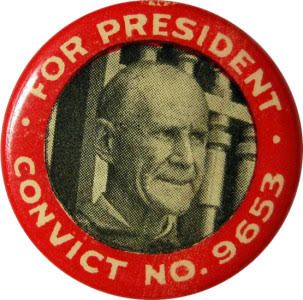

Eugene Debs was convicted of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 for an anti-war speech, then ran for president under the Socialist Party banner from a federal prison in Alabama in 1920. Debs’ supporters handed out campaign buttons for "Prisoner 9653." The candidate who won the presidency that year, Warren Harding, eventually commuted Debs’ 10-year sentence, said James Robenalt, a lawyer who has written about the relationship between Debs and Harding.

A Eugene Debs campaign button from 1920 (public domain)

State constitutions and laws include provisions that say people convicted of felonies can’t run for office, but these provisons apply only to state or local candidates.

When Arkansas tried to enact term limits on federal offices in 1992 — in effect, adding an additional qualification for federal office that was not in the Constitution — the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the law.

Although that ruling addressed races for the U.S. House and Senate directly, "there is general agreement that this extends to presidential candidates, too," Derek Muller, a University of Iowa law professor, previously told PolitiFact. "That means a state cannot prohibit indicted or convicted felons from running for president."

This decision aims to prevent states from driving presidential selection by imposing additional qualifications that would become, potentially, a patchwork that few candidates could meet or that some states could be manipulated to enable some states to collude to disqualify candidates, said Rebecca Green, a College of William & Mary election law professor.

A candidate who is incarcerated would not be able to appear in person on the campaign trail. But experts say the chance of incarceration before trial, even temporarily, is effectively zero.

"Given the fact that he is not really a flight risk, has no criminal record, and would be facing a charge for a nonviolent offense, he will certainly be released on his own recognizance," meaning no bail would be set if he is charged, said Ric Simmons, an Ohio State University law professor. "It is possible they will seize his passport, but that seems unlikely, and even if they did, that wouldn't really affect his presidential campaign in any significant way."

Experts said "arrest" is a valid term for what would happen, though they added that there are important differences between Trump’s situation and a more typical arrest.

"‘Arrest’ is still legally the proper term, since he will technically be ‘seized’ by the state," Simmons said. "But it is not what most people think of as an ‘arrest,’ since he is not likely to be captured by law enforcement."

The more likely scenario is that Trump would "surrender himself," Simmons said.

If Trump is taken into New York custody, "he will need to be booked and fingerprinted," said Joan Meyer, a partner with the law firm Thompson Hine, a former Justice Department lawyer. "The arguments are over whether they will make him do a ‘perp walk,’ which is very humiliating. I don’t think that will happen due to his past federal office, his complaining and calls for protest, and congressional outcry."

If he enters custody, Trump "will undergo the same process as any other person who is charged with a crime," Simmons said. "He will be given a court date for an arraignment, which may happen the same day as the arrest, or may be set into the future."

For a typical defendant, arraignment would be held on the same day as the arrest, Simmons said, but this can mean the defendant waits in custody for six to 24 hours before going before a judge. "This may not happen with Trump, given the security risks to him and of course his status as a former president," Simmons said.

New York should be able to act essentially on its own.

"New York is not subject to any federal law or guidelines in how it will proceed, other than, of course, the federal Constitution, which sets procedural limits regarding search and seizure, interrogations, and due process," Simmons said.

There is a section of federal law that says current members of the federal government acting "in an official or individual capacity" are allowed to have state charges reassigned to federal court. This could be an argument Trump’s legal team makes if he is charged with election interference in a separate case in Georgia. But the money allegedly paid to Daniels in the New York case, Simmons said, occurred weeks before Trump was elected president and months before he took office, meaning he was a private citizen at the time and thus not subject to this provision of the law.

Staff writer Amy Sherman contributed to this article.

Our Sources

New York Times, "Inside the payoff to a porn star that could lead to Trump’s indictment," March 19, 2023

CNN, "Trump says he expects to be arrested Tuesday as New York law enforcement prepares for possible indictment," March 19, 2023

CNBC, "Trump grand jury live updates: Expected indictment in payoff to porn star Stormy Daniels," Mar. 20, 2023

U.S. Constitution, Article II Clause 5

U.S. Supreme Court, U. S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, 1995 ruling

Smithsonian magazine, When America’s most prominent socialist was jailed for speaking out against World War I, June 15, 2018

Slate, Can Trump run for president from prison? May 26, 2021

NPR, Conspiracy theorist and frequent presidential candidate Lyndon LaRouche dies At 96, Feb. 14, 2019

Washington Post, 100 years ago, a president forgave his opponent’s alleged subversion, Jan. 6, 2022

PolitiFact, Can a convicted felon run for Congress from jail? June 25, 2013

PolitiFact, "Does running for president protect Donald Trump from legal issues? No," Nov. 11, 2022

PolitiFact, "Can Donald Trump run for president if charged and convicted of removing official records?" Aug. 9, 2022

PolitiFact, "Ask PolitiFact: Can Donald Trump run for president if indicted or convicted of a crime?" March 7, 2022

Email interview, Rebecca Green, William & Mary law professor, March 4, 2022

Email interview, Derek Muller, University of Iowa law professor, March 4, 2022

Email interview with Joan Meyer, partner with the law firm Thompson Hine, March 20, 2023

Email interview with Stanley Brand, distinguished fellow in law and government at Penn State Dickinson Law, March 20, 2023

Email interview with James Robenalt, partner with the law firm Thompson Hine, March 20, 2023

Email interview with Ric Simmons, Ohio State University law professor, March 20, 2023