Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

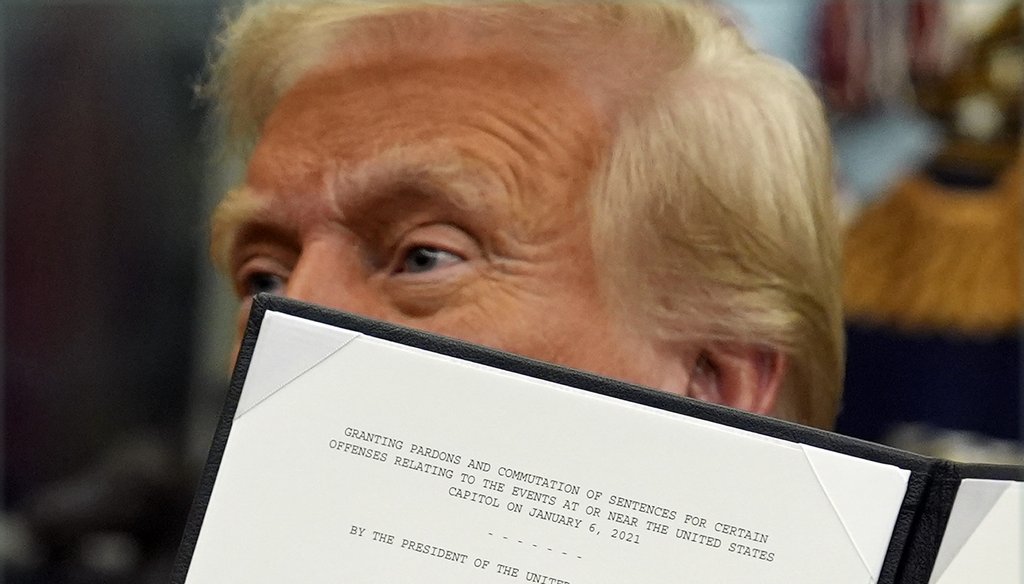

President Donald Trump signs an executive order pardoning about 1,500 defendants charged in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol in the Oval Office of the White House, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

Citing a portion of a news article, conservative political commentator Dinesh D’Souza argued in an Instagram post that people who accept presidential pardons admit guilt.

-

Being pardoned doesn’t equal a sweeping admission of guilt and there’s no formal mechanism for accepting a pardon, constitutional law experts told PolitiFact.

-

Former President Joe Biden said his pardons of retired U.S. Army Gen. Mark Milley, Dr. Anthony Fauci and former Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., “should not be mistaken as an acknowledgment that any individual engaged in any wrongdoing.” Sometimes presidents use their pardon powers not just to forgive, but to exonerate, experts said.

Presidential pardons abound in recent days.

As his term ended, former President Joe Biden issued a series of presidential pardons — including several for people not currently charged with crimes. And one of President Donald Trump’s first acts following his Jan. 20 inauguration was to pardon or commute the sentences of the more than 1,500 people charged with crimes during the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

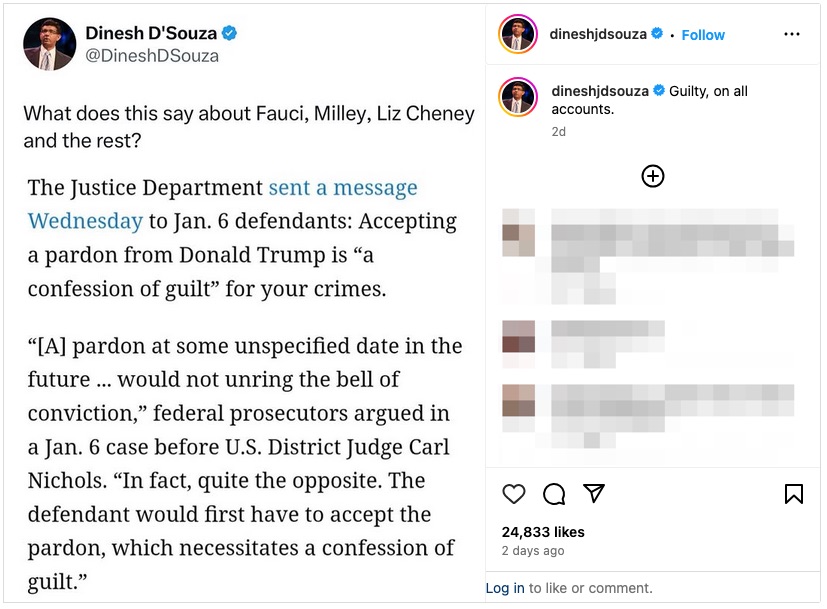

In a Jan. 20 X post before Trump was sworn in, conservative political commentator Dinesh D’Souza highlighted a December 2024 Politico report that said the Justice Department told Jan. 6, 2021, defendants that if they accepted a pardon from Trump, it represented a "confession of guilt" for their crimes.

D’Souza shared a screenshot of the X post that included a portion of the Politico article quoting federal prosecutors in a Jan. 6, 2021, case: "(A) pardon at some unspecified date in the future ... would not unring the bell of conviction. In fact, quite the opposite. The defendant would first have to accept the pardon, which necessitates a confession of guilt."

"What does this say about Fauci, Milley, Liz Cheney and the rest?" D’Souza asked, in his X post, referring to former White House medical adviser Dr. Anthony Fauci, retired U.S. Army Gen. Mark Milley and former Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., all of whom were among the people Biden preemptively pardoned Jan. 20 just before D’Souza posted his claim. To his Instagram post, D’Souza added the caption: "Guilty, on all accounts."

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

(Screenshot from Instagram)

This post was flagged as part of Meta’s efforts to combat false news and misinformation on its News Feed. (Read more about our partnership with Meta, which owns Facebook, Instagram and Threads.)

Politico’s reporting and D’Souza’s assertions about the preemptive pardons conveying guilt raised a question: Does getting pardoned equal a confession of guilt?

Constitutional law experts told PolitiFact that it’s not that simple: Being pardoned doesn’t equal a sweeping admission of guilt and there’s no formal mechanism for accepting a pardon — some pardons have been rejected.

We tried contacting D’Souza through his online store and Instagram account, and received no response before publication.

What does federal legal precedent tell us about pardons and guilt?

Bernadette Meyler, a Stanford Law School law professor, said no — a pardon doesn’t signal a person confessed guilt.

"A pardon simply removes any legal consequences from the relevant acts rather than making an assumption about guilt or innocence," she said. "However, because people in the past have worried about seeming guilty if they accept a pardon, the Supreme Court has held that pardons are not valid if they are rejected."

After Trump issued the Jan. 6, 2021, pardons, at least one convicted defendant, Pamela Hemphill, 71, of Boise, Idaho, made headlines saying she would refuse to accept the pardon on grounds that accepting it would be an "insult" to Capitol Police.

The Supreme Court reinforced on multiple occasions that people can reject pardons. In its 1833 United States v. Wilson ruling, the court held that a pardon is a legal deed that must be delivered to be valid "and delivery is not complete without acceptance." A recipient could refuse the pardon, and "we have discovered no power in a court to force it on him," the court wrote.

In 1915, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Burdick v. United States that rather than accept a pardon and testify, people could refuse presidential pardons and instead invoke their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Brian Kalt, law professor at Michigan State University’s College of Law, said that the idea that accepting a pardon is equivalent to admitting guilt is "based on a widespread misunderstanding" of the Burdick ruling, however.

The ruling included a line saying a pardon "carries an imputation of guilt; acceptance a confession of it."

Kalt said the court explored reasons someone might refuse a pardon and "noted that as a practical matter pardons make the recipient look guilty" or as if the person has something to be pardoned for.

"It is certainly true that as a practical matter, and a matter of public opinion, a pardon can make the recipient look guilty," Kalt said. "But sometimes people overread Burdick and say that accepting a pardon has some sort of formal legal effect of declaring someone guilty. That is not the case."

Dan Kobil, a law professor at Capital University Law School, said the Supreme Court’s 1927 Biddle v. Perovich ruling muddied the issue of pardons and guilt, holding that it wasn’t necessary for someone to accept a commutation from a death sentence to life in prison for the sentence to be reduced.

"Just as the original punishment would be imposed without regard to the prisoner’s consent and in the teeth of his will, whether he liked it or not, the public welfare, not his consent, determines what shall be done," the ruling said.

As a result, more people now disagree about whether being granted clemency "invariably implies that someone was guilty of a crime," Kobil said.

That question is at the heart of two federal inmates’ recent efforts to block death sentence commutations that Biden granted.

What do legal experts make of D’Souza’s assertion that the Fauci, Milley and Cheney pardons prove their guilt?

Biden’s statement pardoning Milley, Fauci and Cheney said the pardons "should not be mistaken as an acknowledgment that any individual engaged in any wrongdoing, nor should acceptance be misconstrued as an admission of guilt for any offense."

Legal experts told PolitiFact that sometimes presidents use their pardon powers not just to forgive, but to exonerate, absolving them from any blame at all.

Kobil said "based on all of the information we have available," no one has credibly alleged Cheney, Fauci and Milley committed any crimes, meaning their pardons "are more akin to those pardoned based on complete exoneration."

Kalt said there’s "really no way" to attribute guilt if the president’s whole point was that these people did nothing wrong.

Richard Painter, a University of Minnesota Law School law professor who served as the chief White House ethics lawyer under President George W. Bush, added that there’s no formal mechanism for accepting a pardon.

"I don’t think the pardon becomes ineffective simply because the person pardoned remains silent," Painter said. That means if the pardoned person were later indicted for a crime within the pardon’s scope, their lawyers could invoke the pardon as a defense, he said.

It’s unclear whether all of the people Biden pardoned will accept their pardons.

However, even if someone did so formally as a defense against indictment, Painter said that wouldn’t immediately signal that person’s guilt.

For example, Painter said he knew of no crime Cheney had committed. If someone tried to indict Cheney to force her to accept the pardon, Painter said he wasn’t convinced by the argument that she would be admitting guilt by doing so.

RELATED: Biden commutes sentences of all but three convicts on federal death row

Our Sources

Dinesh D’Souza Instagram post, Jan. 20, 2025

Interview with Richard Painter, law professor at the University of Minnesota Law School, Jan. 22, 2025

Email interview with Bernadette Meyler, law professor at Stanford Law School, Jan. 21, 2025

Email interview with Dan Kobil, law professor at Capital University Law School, Jan. 21, 2025

Email interview with Brian Kalt, law professor at Michigan State University’s College of Law, Jan. 22, 2025

Email exchange with Max Guirguis, political science professor at Shepherd University, Jan. 22, 2025

The White House, Statement from President Joe Biden, Jan. 20, 2025

The Associated Press, Trump grants sweeping pardon of Jan. 6 defendants, including rioters who violently attacked police, Jan. 21, 2025

Dinesh D’Souza X post, Jan. 20, 2025

Politico, Justice Department: Jan. 6 defendants who accept pardons will make ‘a confession of guilt,’ Dec. 11, 2024

Justice Department, Effects of a Presidential Pardon, June 19, 1995

Justia, Burdick v. United States, 236 U.S. 79 (1915), Jan. 25, 1915

Library of Congress, Burdick v. United States, Jan. 25, 1915

Justia, Biddle v. Perovich, 274 U.S. 480 (1927), May 31, 1927

Cornell Law School, ArtII.S2.C1.3.6 Rejection of a Pardon, accessed Jan. 22, 2025

Congress.gov, ArtII.S2.C1.3.6 Rejection of a Pardon, Jan. 22, 2025

Library of Congress, The United States v. George Wilson, 1833

Kentucky Political Science Association, The Nature and Extent of Presidential Pardon Power: An Analysis in Light of Recent Political Developments, accessed Jan. 22, 2025

The New York Times, Trump Pardoned Her for Storming the Capitol. ‘Absolutely Not,’ She Said, Jan. 22, 2025

The New York Times, Trump Says ‘America’s Decline Is Over’ as He Returns to Office, Jan. 20, 2025

NBC News, Two death row inmates reject Biden's commutation of their life sentences, Jan. 6, 2025

NBC News, Two prisoners can't legally object to Biden's death row commutations, DOJ argues, Jan. 13, 2025

Office of the Pardon Attorney, Pardons Granted by President Joseph Biden (2021-Present), accessed Jan. 23, 2025