Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

While Border Patrol agents do have some unique permissions that allow access to vehicles and private land within a 100-mile radius from the border, Fourth Amendment protections still require agents to have probable cause before entering and searching a home.

The Supreme Court case Egbert v. Boule deals with whether people whose constitutional rights have been violated can sue individual agents for monetary damages in federal court.

The Supreme Court ruling in no way changes what Border Patrol agents can and cannot do.

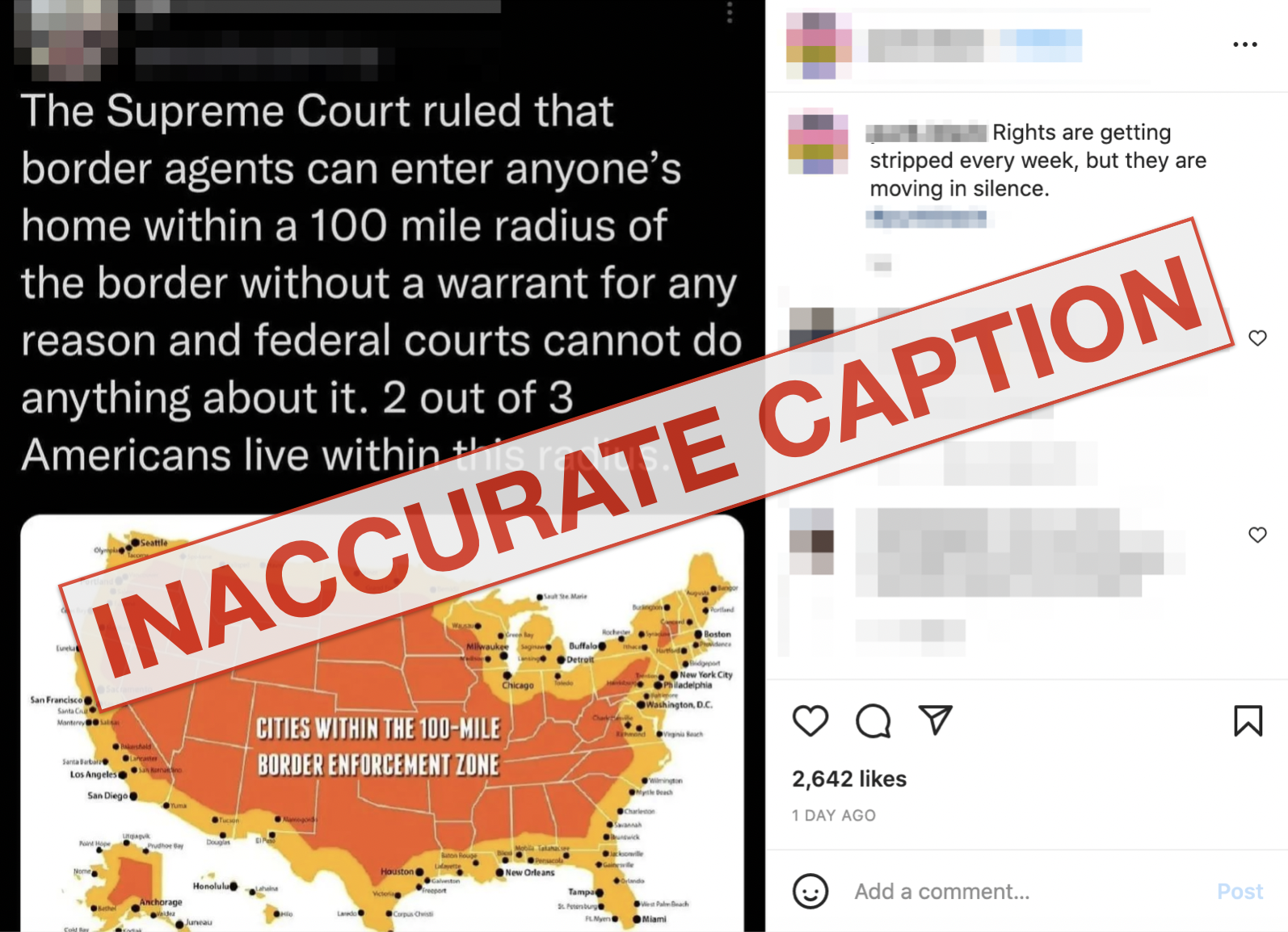

Amid the flurry of June Supreme Court rulings, an alarming post gained traction on Instagram claiming that the court gave border agents unfettered permission to enter the homes of nearly 200 million Americans.

"The Supreme Court ruled that border agents can enter anyone’s home within a 100-mile radius of the border without a warrant for any reason and federal courts cannot do anything about it," read the June 21 post. "2 out of 3 Americans live in this radius."

This post was flagged as part of Facebook’s efforts to combat false news and misinformation on its News Feed. (Read more about our partnership with Facebook.)

(Screengrab from Instagram)

The post, which was deleted while we were checking its claim, featured an orange map of the U.S. with a thick yellow line denoting a "border enforcement zone" and highlighted cities within that area. We found similar posts on Facebook and Twitter.

The post gets some small details correct: There is a 100-mile zone where agents have certain unique permissions, and nearly two-thirds of Americans live within it, according to the ACLU.

But the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution still protects "against unreasonable searches and seizures" without probable cause — including by Border Patrol agents. And the Supreme Court’s ruling in Egbert v. Boule did not change what Border Patrol agents are permitted to do.

The ruling addressed how citizens can legally respond if they are victims of constitutional violations.

While critics of the decision argue that the ruling makes it more difficult for agents to be held accountable when they do violate people’s rights, the Instagram post’s characterization of its effect misses the mark.

Limits on what exactly federal Border Patrol agents can and can’t do are outlined in the Immigration and Nationality Act. The act, first passed by Congress in 1952 and amended in 1965, serves as the primary immigration legislation in the U.S. Among its many provisions, the law outlines several unique powers of Border Patrol agents that were established "for the purpose of patrolling the border to prevent the illegal entry of aliens into the United States."

The law specifies that within "100 air miles" of any "external boundary" of the U.S. border (which includes coastlines), Border Patrol agents can, without a warrant, "board and search for aliens any vessel within the territorial waters of the United States and any railway car, aircraft, conveyance, or vehicle."

This means that within 100 miles from the border, Customs and Border Protection agents can board buses and trains and request immigration documentation from passengers without a warrant or probable cause. Agents may also pull over vehicles if they have "reasonable suspicion" of an immigration violation according to the ACLU. The provision continues, stating that within 25 miles of the border, agents are allowed "to have access to private lands, but not dwellings," for the purpose of preventing illegal immigration.

So, while agents do have access to vehicles (within 100 miles) and private lands (within 25 miles) the law explicitly excludes access to people’s homes. And the Fourth Amendment still protects "against unreasonable searches and seizures" without probable cause. To search a vehicle or a dwelling, Border Patrol agents still need to demonstrate probable cause, or reasonable belief that a crime has been committed.

So, although CBP agents do have some unique powers within the 100-mile zone, those powers don’t include the ability to enter people’s homes without warrants, as the claim states.

"The Supreme Court did not alter the border search exception law in any way" said Art Arthur, resident fellow in law and policy at the Center for Immigration Studies, an organization that supports low levels of legal immigration.

On June 8, 2022, the Supreme Court released its 6-3 ruling in favor of Erik Egbert, the Border Patrol agent named in Egbert v. Boule.

Robert Boule sued Egbert after he said the agent in 2014 entered his business, the Smuggler’s Inn on the U.S.-Canada border in Blaine, Washington, to investigate a guest suspected of entering the country illegally. Boule, who had previously served as a confidential informant for CBP, asked Egbert to leave. He claimed Egbert then "became violent, and threw Boule first against the vehicle and then to the ground."

Boule sued, seeking monetary damages for violations to his constitutional rights, claiming use of excessive force and retaliation.

The court found that Boule was not entitled to seek damages for the excessive force and retaliation of Egbert. But the court "did not sanction the agent’s unconstitutional actions or grant agents permission to violate people’s rights in the future," according to the ACLU. The court’s decision ultimately limits the scope of what is called a "Bivens action" — "a lawsuit for damages when a federal officer who is acting in the color of federal authority allegedly violates the U.S. Constitution," according to a definition from Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute.

Bivens actions have been used in federal courts since 1971, but "the Supreme Court… has so many times said that Bivens really has limited application. And if you follow the trend of Bivens, then it is not that surprising to see what [the Supreme Court] did in this case," said Muzaffar Chishti, senior fellow at the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute.

For people seeking damages due to a violation of constitutional rights, suing an individual CBP agent through a Bivens action in federal courts is no longer a viable option, Chishti said.

The majority opinion written by Justice Clarence Thomas said that, except for rare circumstances, it is the job of Congress, not the courts, to address these claims.

In the dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor disagreed with the ruling writing that thousands of "CBP agents are now absolutely immunized from liability in any Bivens action for damages, no matter how egregious the misconduct or resultant injury…including those engaged in ordinary law enforcement activities, like traffic stops, far removed from the border."

The ACLU similarly expressed concern that the limiting of Bivens actions removes important deterrents to misconduct and limits accountability for federal agents.

"They have been given more of a green signal to act aggressively in the pursuit of their job than they did before Egbert," Chishti said.

An Instagram post claimed that the Supreme Court ruled that Border Patrol agents can enter any home within 100 miles of the border without a warrant and that federal courts have no way to address it.

The Supreme Court ruling in Egbert v. Boule does not grant any new powers to Border Patrol agents, who still cannot enter any home without a warrant or probable cause under the Fourth Amendment.

The ruling did narrow the path that victims of excessive force and other constitutional violations have to seek monetary damages from those agents through federal courts. Critics of the decision argue the ruling makes it more difficult for agents to be held accountable when they do violate people’s rights.

We rate this statement Mostly False.

Instagram Post, (deleted at the time of publishing), June 21, 2022.

Tweet, June 9, 2022

Facebook post, June 10, 2022

Email Interview with Andrew "Art" Arthur, Resident Fellow in Law and Policy at the Center for Immigration Studies, June 22, 2022

Interview with Muzaffar Chishti, Senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute, June 23, 2022

Email interview with Alexander Reinert, Cardozo Law Professor at Yeshiva University, June 23, 2022

Email Interview with James E Pfander, Northwestern University Law professor, June 24, 2022

Verify This, "No, warrantless home searches are not legal within 100 miles of the U.S. border," June 17, 2022

U.S. Supreme Court, "21-147 Egbert v. Boule," June 8, 2022

ACLU, "The Constitution in the 100-Mile Border Zone," accessed June 23, 2022

Bloomberg, "Mapping Who Lives in Border Patrol's '100-Mile Zone'," May 14, 2018

Library of Congress, "Fourth Amendment," accessed June 23, 2022

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, "Immigration and Nationality Act," accessed June 22, 2022

Immigration and Nationality Act, "8 USC 1357: Powers of immigration officers and employees," accessed June 22, 2022

Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, "8 US Code § 1357 - Powers of immigration officers and employees," accessed June 22, 2022

Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, "8 CFR § 287.1 - Definitions," accessed June 22, 2022

Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, "Bivens Actions," accessed June 22, 2022

Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, "Probable Cause," accessed June 23, 2022

ACLU, "Know Your Rights: In the 100-Mile Border Zone | American Civil Liberties Union," June 21, 2018

Oyez, "Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Federal Bureau of Narcotics," accessed June 24, 2022

The Washington Post, "Supreme Court shields Border Patrol agent from excessive-force claim," June 8, 2022

U.S. House of Representatives, "Federal Tort Claims Act," accessed June 24, 2022

Alexander Reinert, "Measuring the Success of Bivens Litigation and its Consequences for the Individual Liability Model," September 18, 2009

ACLU, "Four Things to Know About the Supreme Court's Ruling in Egbert v. Boule," June 27, 2022

In a world of wild talk and fake news, help us stand up for the facts.