Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Taliban special force fighters arrive at the Hamid Karzai International Airport after the U.S. military's withdrawal, in Kabul, Afghanistan. (AP Photo/Khwaja Tawfiq Sediqi)

When the Taliban controlled Afghanistan two decades ago, they were known for banning music and television, conducting public executions and imposing a fierce interpretation of Islamic law that sharply restricted the rights of women.

Today, they intend to run the nation again — in very different times — and it’s not clear what that might mean. In official statements, Taliban leaders put forth an image that is less draconian than the late 1990s, before U.S-led forces drove them from power.

But it’s still too soon to tell whether they’ll live and rule by those words.

Here are answers to some key questions about today’s Taliban, based on what we know now.

The Taliban’s leadership roster is dominated by ethnic Pashtuns who have overseen the fight against the U.S.-backed Afghan government, the U.S. and its allies.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

The supreme leader is Mawlawi Hibatullah Akhundzada, who comes from a religious background. During the Taliban regime from 1996 to 2001, he oversaw the administration of civil and religious law. He comes from the powerful Pashtun Nurzai clan.

Under Akhundzada are three deputies who will play key roles in the newly formed government:

-

Abdul Ghani Baradar is expected to oversee the daily running of a new government. He has been the head of political affairs and has been the point man in discussions with the remnants of the U.S.-backed Afghan government for the transfer of power to the Taliban. Baradar had been a prisoner in Pakistan, but at the request of former President Donald Trump, he was released in 2018 to lead peace negotiations in Doha, Qatar.

-

Sirajuddin Haqqani has been a key deputy leader. Haqqani leads the Haqqani network, a powerful militant organization based in Pakistan that holds sway in eastern Afghanistan. In September 2011, the Haqqani network was responsible for a daylong assault on multiple targets in Kabul, including the U.S. Embassy and the Afghan presidential palace.

-

Muhammad Yaqoob has been mentioned in several reports as a potential defense minister. He has overseen much of the Taliban’s military activity, a post he’s held since 2020. His father, Mullah Muhammad Omar, was the Taliban’s founding leader.

Under this core leadership are many Pashtuns, but also members of other ethnic groups. Qari Din Mohammad Hanif is a 66-year-old ethnic Tajik from the northern part of Afghanistan. He was the minister for planning and higher education during the Taliban regime. Mawlawi Abdul Salam Hanafi, an ethnic Uzbek, served as a provincial governor as well as deputy minister during the Taliban rule.

There are many ways the Taliban could split into competing factions in trying to govern a multiethnic nation scarred by decades of war. The Pashtun ethnic group makes up about 40% of Afghanistan’s population. Within the Pashtun, there are a handful of leading clans. Beyond the Pashtun, there are many other ethnolinguistic groups, including Tajiks, Uzbeks and Turkmen.

"They might not be able to govern if they can’t keep these competing interests in check," said Naval Postgraduate School professor Thomas H. Johnson, who has studied Afghanistan and the region for many years. "Each group might aim to hold on to as much power as possible. The worst-case scenario would be a breakdown into civil war."

Exacerbating these group tensions are differences between older, more pragmatic leaders, and younger, more radical ideological ones. "It might be months or a year before we know how this turns out," Johnson said.

The Taliban controlled most of Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001, running a strict Islamic fundamentalist state and providing a base for Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida, which attacked the U.S. on Sept. 11, 2001. When the U.S and its allies retaliated, forcing the Taliban from power in Kabul, the group scattered, with many members finding refuge in neighboring Pakistan.

By 2003, when the U.S. launched its invasion and occupation of Iraq, the Taliban began to regroup. Around 2006, the Taliban established elements of shadow governments in provinces where they held some influence. The formal provincial officials remained in place, but the Taliban had both military and civilian leaders advancing their agenda. According to one estimate, by 2010, there were about 500 Taliban judges settling legal disputes among Afghans.

According to a research paper from the Overseas Development Institute, a London-based think tank, 2010 marked a pivot in Taliban strategy. They shifted from primarily military control to a blended strategy that included ordinary public administration.

By 2011, the Taliban had signed agreements with 26 international humanitarian nongovernmental organizations. Buy-in was uneven among local Taliban leaders, who might cut off access or attack aid workers suspected of spying, but central leadership attempted to impose policies that accommodated the NGOs.

By 2017, their governing apparatus was extensive, shaping health care, education and tax collections.

"They regulate utilities and communications, collecting on the bills of the state electricity company in at least eight of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces and controlling around a quarter of the country’s mobile phone coverage," the report said.

As rulers again in Kabul, the Taliban face the daunting challenge of finding capable managers.

Johnson at the Naval Postgraduate School said he was in touch recently with a deputy minister with the Afghan national government that collapsed. The minister said he went to his old office to get some materials. The Taliban occupiers denied him entry, but then, according to Johnson’s account, they next asked the official if he would want to run the ministry under them.

The Taliban operate a robust social media operation. They are active on Twitter and Facebook and in 2015 launched Telegram and WhatsApp channels. An estimated 90% of Afghans have access to a mobile device, and the Taliban are able to quickly produce and share infographics and short videos.

They have shown nuance in their communications with the international community. When an anti-Muslim terrorist gunned down 51 Muslims at mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, the Taliban called not for retribution, but for an investigation.

In the winter of 2020, the Taliban deputy leader Haqqani published an op-ed in the New York Times.

"I am confident that, liberated from foreign domination and interference, we together will find a way to build an Islamic system in which all Afghans have equal rights," Haqqani wrote Feb. 20, 2020. "Where the rights of women that are granted by Islam — from the right to education to the right to work — are protected, and where merit is the basis for equal opportunity."

The Taliban have consistently sought international recognition. Equally consistently, they speak of strict observance to their interpretation of Islamic law. It remains to be seen how they will balance the two goals, and how their need for international financial support might shape their policies.

The Taliban maintains a relationship with al-Qaida, the international terror group blamed for 9/11 and scores of other terrorist attacks, bombings and assassinations around the world since the early 1990s.

"The primary component of the Taliban in dealing with al-Qaida is the Haqqani Network," a June U.N. Security Council report said. "Ties between the two groups remain close, based on ideological alignment, relationships forged through common struggle and intermarriage."

Al-Qaida members are in Afghanistan — contrary to claims by President Joe Biden — although the Taliban have attempted to exert some control by registering them as foreign fighters.

The Taliban generally oppose the Islamic State, a violent insurgent and terrorist group that ruled parts of Iraq and Syria in the mid 2010s and had affiliates in other countries. (It is also known as ISIS or ISIL.)

According to the final report of the congressionally mandated Afghanistan Study Group, "The Taliban have taken active measures, sometimes with tacit U.S. support, against the Islamic State, driving it out of northwest Afghanistan and significantly circumscribing its mobility in the east."

The Islamic State’s Afghan offshoot, ISIL-K, blamed for the Aug. 26 terror attack in Kabul that killed 13 U.S. service members, competes with the Taliban for members. It has positioned itself as a hardline group and aims "to recruit disaffected Taliban and other militants to swell its ranks," according to the U.N. Security Council.

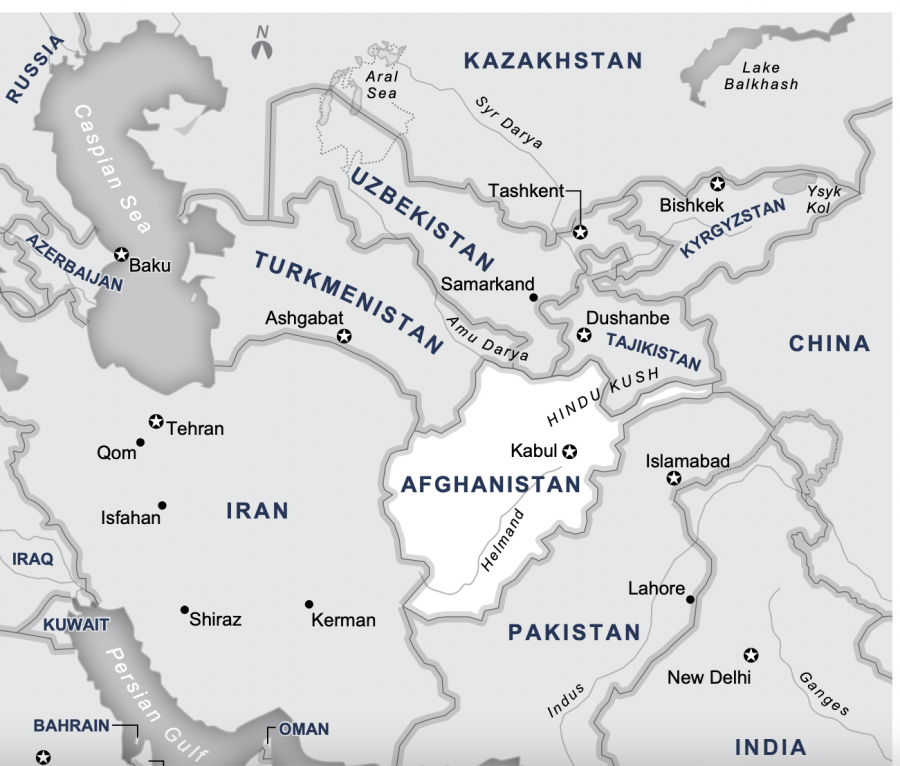

Pakistan, with its 1,600-mile border with Afghanistan, is deeply involved in the country’s affairs. It has provided safe territory for the Taliban and supported them during their 20-year battle with the U.S. and its allies. Pakistan treats the Taliban as a reliable ally against India, its archenemy, and has good working relationships with the Taliban leadership.

At the same time, some analysts believe that Pakistan is concerned that Afghanistan under Pashtun rule could trigger unrest among the 32 million ethnic Pashtuns in Pakistan.

Map of Afghanistan region. (U.S. Institute of Peace)

Iran, Afghanistan’s neighbor on the west, has several key interests. High on its list is protecting the Shia minority in Afghanistan. As an opponent of the U.S. presence in the region, Iran has aided the Taliban. Trade between the two nations stands at about $2.8 billion a year, and Iran’s port in Chabahar offers landlocked Afghanistan access to international markets.

Officially, Russia has labeled the Taliban as a terrorist entity, but Russia has also called on the international community to lift the current freeze on Afghanistan’s financial reserves. Russia’s presidential envoy for Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, called Aug. 30 for an international conference aimed at supporting the country’s recovery under Taliban leadership.

China and India have economic and political interests that broadly favor a stable Afghanistan, although India remains wary of any coziness between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Talks between the U.S. and the Taliban date back to at least 2013 during the Obama administration. The U.S. hoped to bring the Afghan government into the negotiations in Doha. Talks limped along, and the only signed deal that ever emerged came in February 2020, and the Afghan government did not participate.

Under the Feb. 29, 2020, agreement between the Trump administration and the Taliban, the U.S. and its allies agreed to withdraw their military forces within 14 months of the agreement’s announcement. In exchange, the Taliban agreed that it would not allow groups in Afghanistan, including al-Qaida, to threaten the security of the United States and its allies.

The agreement also called for negotiations between the Taliban and the Afghan government, starting March 10, 2020. Those discussions started late and never went far.

The agreement also led to the release of 5,000 Taliban and ISIS-K prisoners held by the Afghans. The Afghan government resisted, but under American pressure, eventually complied.

At least some of the released prisoners returned to fighting the Afghan forces.

Our Sources

Overseas Development Institute, Life under the Taliban shadow government, June 2018

United Nations Security Council, Twelfth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, June 1, 2021

Congressional Research Service, Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy: In Brief, June 11, 2021

United States Institute of Peace, Afghanistan Study Group Final Report,February 2021

Defense Technical Information Center, The Afghan Taliban: Evolution Of An Adaptive Insurgency, June 1, 2019

U.S. State Department, Agreement for bringing peace to Afghanistan, Feb. 29, 2020

New York Times, The Taliban are poised to name a supreme leader and map out their government, Sept. 1, 2021

United News of India, Taliban to announce government soon, Aug. 31, 2021

MEHR News Agency, Taliban announces names of defense, foreign ministers, Aug. 31, 2021

Atlantic Council, How the Taliban did it: Inside the ‘operational art’ of its military victory, Aug. 15, 2021

Anadolu Agency, Key leaders of Taliban, the 'students' of warfare, Aug. 17, 2021

U.S. National Counterterrorism Center, Haqqani network, accessed Aug. 30, 2021

Atlantic Council, Before the Taliban took Afghanistan, it took the internet, Aug. 26, 2021

New York Times, What We, the Taliban, Want, Feb. 20, 2020

China Global Television Network, Graphics: The evolution of the Taliban, Aug. 24, 2021

Washington Post, The world should unfreeze Afghanistan’s reserves and pour in aid to rebuild the country, Russia says, Aug. 30, 2021

Washington Post, U.S. to launch peace talks with Taliban, June 18, 2013

New York Times, Taliban Step Toward Afghan Peace Talks Is Hailed by U.S.,June 18, 2013

PolitiFact, Joe Biden said that al-Qaida is 'gone' from Afghanistan. That’s wrong, Aug. 23, 2021

PolitFact, Mitt Romney accurately says Trump administration worked to free 5,000 Taliban prisoners, Aug. 31. 2021

Interview, Thomas. H. Johnson, associate professor, Naval Postgraduate School, Aug. 31, 2021