Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

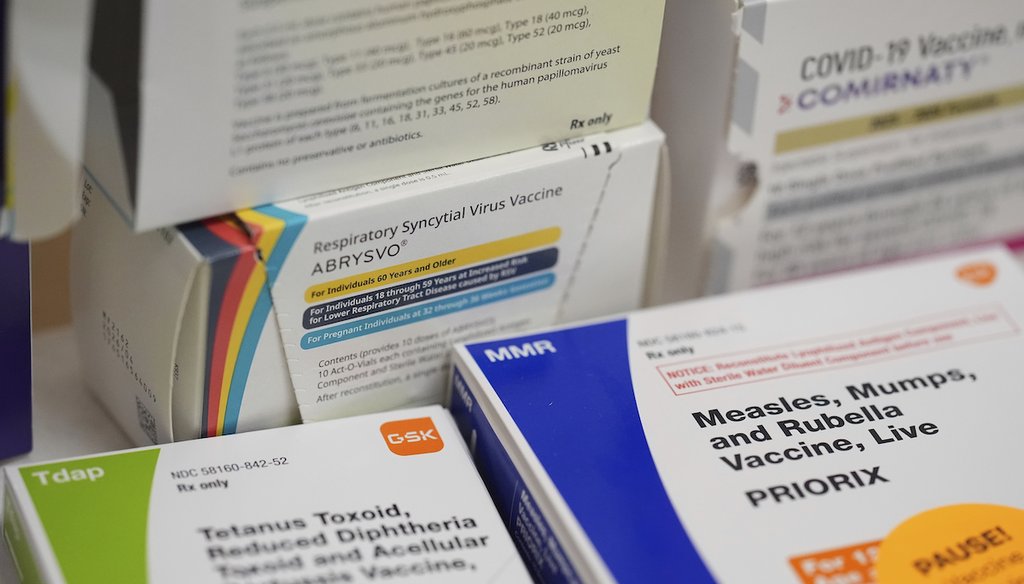

Boxes of various vaccines are seen inside a CVS pharmacy, Sept. 9, 2025, in Miami. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

It probably won’t immediately become more difficult for children to get the vaccines that the federal government removed from its universal recommendations.

-

Insurance companies so far say that they intend to cover through 2026 all vaccines that the Centers for Disease Control previously recommended, including vaccines against hepatitis A, hepatitis B and rotavirus. It’s unclear what will happen after that.

-

Under the federal government’s change, several vaccines will only be available to patients after consulting with a medical professional. That adds hurdles that doctors expect will ultimately reduce how widely people get vaccinated.

The federal government recently made sweeping changes to its list of recommended childhood vaccines, raising a host of questions for parents.

Until early this year, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had recommended every child be routinely immunized against 17 diseases. On Jan. 5, however, federal officials unilaterally dropped the recommendations for immunization against five of those diseases.

Vaccines against hepatitis A, hepatitis B, rotavirus, meningococcal disease and the flu are now recommended only for children considered at high risk of serious illness — or after "shared clinical decision-making," or consultation between doctors and parents.

Doctors told PolitiFact they did not expect the vaccine schedule changes to immediately make it more difficult to get your child vaccinated against these diseases.

In the future, though, that could change.

"The practical impact isn’t that motivated families suddenly can’t access vaccines, but that the system becomes less reliable and more dependent on a parent knowing what to request and when," said Dr. Jake Scott, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford Medicine.

Here are some things we learned.

An immunization poster is seen outside of an examination room where Tammy Camp, left, and Summer Davies, both with the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, speak to The Associated Press in Lubbock, Texas, Feb. 25, 2025. (AP)

Q: Can kids still get the vaccines that the CDC just removed from the routine childhood vaccination schedule? Will health insurance cover it?

A: Yes, children can still get the vaccines. And in the immediate aftermath of the CDC’s changes, most families should still be able to without paying out-of-pocket insurance fees, Scott said.

A Jan. 5 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services fact sheet said that all immunizations that the CDC previously recommended would continue to be covered by Affordable Care Act insurance plans and federal programs including Medicaid, Vaccines for Children, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. The Trump administration also said insurance companies are still required to cover all of the vaccines without cost-sharing. Insurance companies have largely echoed this message.

Responding in September to different vaccine recommendation changes, AHIP, a national trade association for health insurers, said health plans would cover through 2026 the updated COVID and flu vaccines and all other immunizations that the CDC recommended as of Sept. 1, 2025.

An AHIP spokesperson confirmed Jan. 13 that was still true. A Blue Cross Blue Shield Association spokesperson, meanwhile, said its companies would continue covering all immunizations the CDC recommended as of Jan. 1, 2025, without cost-sharing.

Q: What does "shared clinical decision making" mean?

A: If a vaccine is now recommended based on "shared clinical decision making," that means a patient — or, in the case of children, their parent or guardian — must consult with a health care provider before getting it, according to the CDC.

These health care providers can include primary care physicians, specialists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, and pharmacists, the CDC says on its website. They are supposed to talk with the patient about a vaccine’s benefits and risks.

How much authority certain health care providers have to provide that information varies by state, according to the Common Health Coalition, a union of health care organizations. So while medical assistants and pharmacy techs can administer some vaccines in most states, they likely aren’t qualified to have conversations that satisfy the shared clinical decision making requirement, the coalition said.

In practice, this means parents might need to plan vaccine conversations in advance by booking additional doctor appointments. Ultimately, this extra step could make it harder and more complicated for people to get vaccinated.

"If your 3-year-old child had their wellness visit in June, under these rules, they can’t go to a flu or COVID mass vaccination clinic and get their vaccines in the fall," said Dr. Molly O’Shea, a pediatrician and American Academy of Pediatrics spokesperson. "Instead, they need an appointment to discuss the vaccines prior to receiving them."

Even though insurance will cover the vaccine, these additional doctor appointments could come with more office visit charges, copays or deductibles, O’Shea said. "This barrier is undoubtedly going to reduce uptake of vaccines."

Lead medical assistant Maria Teresa Diocales administers the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine to 1-year-old at International Community Health Services, Sept. 10, 2025, in Seattle. (AP)

Q: Why are medical professionals worried?

A: The decision to drop multiple vaccine recommendations without new science or data alarmed public health professionals.

Recategorizing a vaccine as needing shared clinical decision making could send the message that some kids shouldn’t get it, O’Shea said. Organizations including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Medical Association continue to recommend children receive the vaccines removed from the universal recommendations guidelines.

Physicians might find themselves having "to talk parents into what has been a necessary, recommended vaccine despite no shift in the science," O’Shea said.

Plus, vaccine reminder systems that many doctors use weren’t built for this approach.

"The electronic health record systems most practices use are built for binary decisions: this patient needs this vaccine or they don’t," Scott said. Doctors might not be automatically prompted to offer the vaccines or plan to discuss them during a routine office visit, he said.

This poses the biggest problem for vaccines requiring strict timing, such as the two-dose rotavirus vaccine. Dose one is given before age 15 weeks and the series must be finished by 8 months.

"Any delay caused by missed prompts, extra conversations or rescheduling can mean a child ages out of eligibility entirely," Scott said.

Q: How will this change families’ ability to access vaccines in the future?

A: Doctors fear the new changes will reduce how many people get vaccines long term. We aren’t sure what insurers will do after 2026. It’s not clear that they’ll continue to cover all the formerly recommended routine vaccines. And there are other uncertainties.

When a vaccine isn’t considered routine, some practices could stock less of it, especially if they have limited storage, Scott said.

"That tends to push vaccination away from the usual path and toward ‘ask for it,’ which hits hardest for families without a stable medical home, families with transportation and scheduling constraints and families in underserved areas," he said.

It could also be harder to get these vaccines at places such as retail pharmacies, which might not be able to readily accommodate the shared clinical decision making requirement.

Q: How should parents navigate these changes?

A: Doctors recommend parents ask pediatricians what immunization schedule their practice follows.

The American Academy of Pediatrics produces its own recommended vaccine schedule, which, for years, aligned with the CDC’s guidelines.

"For parents who are looking for vaccine guidance that is carefully considered, paced and timed to work with your child’s growing immune system and protecting them when they need it most, the AAP’s vaccine schedule is the best resource," O’Shea said.

If your pediatrician says they plan to follow the AAP schedule, you can say you’d like to follow it as well and proceed with your child’s vaccinations.

"Keep your child’s vaccine record current and accessible," Scott advised. "If you're unsure whether your child is due for something, ask for a printed immunization forecast from the practice or your state registry."

PolitiFact Researcher Caryn Baird contributed to this report.

RELATED: The CDC just sidelined these childhood vaccines. Here’s what they prevent.

Our Sources

Email interview with Dr. Jake Scott, infectious disease specialist and a clinical professor at the Stanford University School of Medicine, Jan. 8, 2026

Email interview with Dr. Molly O’Shea, pediatrician and American Academy of Pediatrics spokesperson, Jan. 9, 2026

Emailed statement from AHIP spokesperson, Jan. 13, 2026

Emailed statement from Kaiser Permanente spokesperson, Jan. 13, 2026

Emailed statement from Blue Cross Blue Shield Association spokesperson, Jan. 14, 2026

Emailed statement from United Healthcare spokesperson, Jan. 13, 2026

The Washington Post, CDC staff ‘blindsided’ as child vaccine schedule unilaterally overhauled, Jan. 7, 2026

PolitiFact, The CDC just sidelined these childhood vaccines. Here’s what they prevent, Jan. 7, 2026

The Washington Post, U.S. overhauls childhood vaccine schedule, recommends fewer shotst, Jan. 5, 2026

CIDRAP, HHS announces unprecedented overhaul of US childhood vaccine schedule, Jan. 5, 2026

PolitiFact, Can I get an updated COVID-19 vaccine this year? Is it available yet? Will insurance cover it?, Aug. 29, 2025

Your Local Epidemiologist, A unilateral change to childhood vaccines: What it means for you, Jan. 6, 2026

NBC News, CDC group endorses adding Covid shots to recommended vaccine schedule, Oct. 20, 2022

NBC News, CDC ends Covid vaccine recommendation for healthy kids and pregnant women, May 27, 2025

Association of Health Care Journalists, Big changes to the CDC’s childhood vaccine schedule: What you need to know, Jan. 9, 2026

AHIP, AHIP Statement on Vaccine Coverage, Sept. 16, 2025

American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Vaccine Schedule 2025, accessed Jan. 13, 2025

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC Acts on Presidential Memorandum to Update Childhood Immunization Schedule, Jan. 5, 2026

KFF, Recent Changes in Federal Vaccine Recommendations: What’s the Impact on Insurance Coverage?, Dec. 16, 2025

HealthCare.gov, Preventive care benefits for children, accessed Jan. 13, 2025

KFF, ACIP, CDC, and Insurance Coverage of Vaccines in the United States, June 13, 2025

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ACIP Shared Clinical Decision-Making Recommendations, accessed Jan. 7, 2025

Common Health Coalition, Shared Clinical Decision-Making Guide on Vaccines for Clinicians, Dec. 16, 2025

Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Rotavirus: The Disease & Vaccines, accessed Jan. 15, 2026

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Child and Adolescent Immunization Schedule by Age (Addendum updated June 27, 2024), archived version accessed Jan. 16, 2026

PharmExec, The American Academy of Pediatrics Breaks with CDC on COVID Vaccine Recommendations, Aug. 19, 2025

American Medical Association, AMA statement on changes to childhood vaccine schedule, Jan. 5, 2026

American Academy of Pediatrics, AAP: CDC plan to remove universal childhood vaccine recommendations ‘dangerous and unnecessary’, Jan. 5, 2026