Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

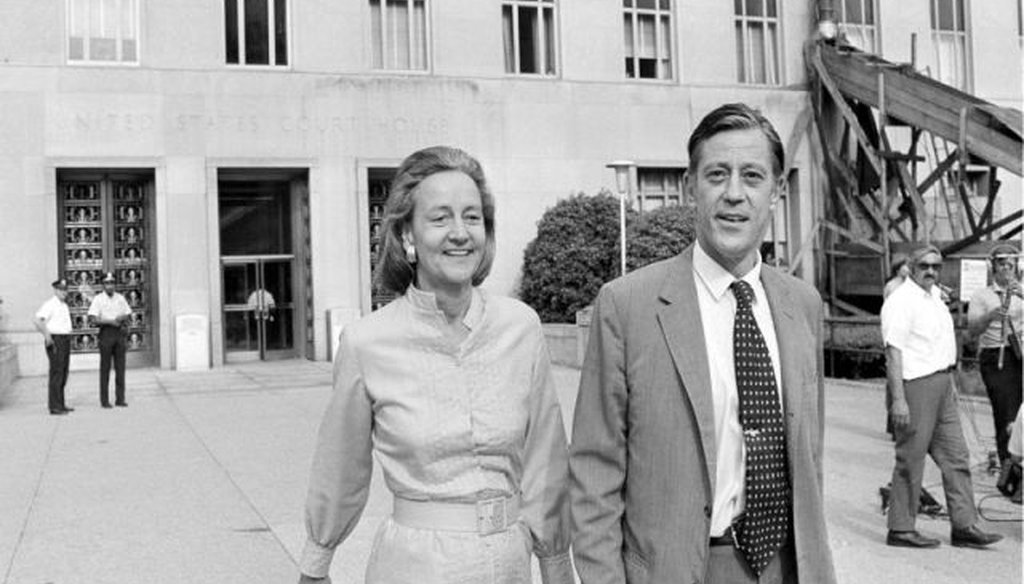

In this June 21, 1971 file photo, Washington Post Executive Director Ben Bradlee and Post Publisher Katharine Graham leave U.S. District Court in Washington (AP Photo, File).

We love movies — the way they transport us to another time and place, showing moments of intimate emotion and high drama. But when movies claim to depict real events, we start thinking like fact-checkers.

Is what they’re showing us basically accurate? Or are we seeing an exaggerated story that bears little resemblance to reality?

This year, we decided to stop wondering and bring our fact-checking methodology with us to the movies. We’ve fact-checked the three nominees for this year’s Best Picture Academy Award that are dramatic interpretations of actual events: Darkest Hour, Dunkirk and The Post.

We researched the history and spoke with experts about the movies, and summed up our findings in three separate reports. (We hope you’ve seen the movies already, because there are plenty of spoilers ahead.)

Darkest Hour depicts Winston Churchill’s first weeks in 1940 as Britain’s prime minister on the eve of World War II and Adolf Hitler’s attacks on the United Kingdom. Actor Gary Oldman portrays Churchill as indomitable and unwavering in his willingness to fight against the Third Reich.

The historical record shows that Darkest Hour takes a few liberties with timing. A dramatic speech Churchill delivers happened days later than the movie claims. The movie suggests that Churchill gave a towering speech in the House of Commons vowing to "go on to the end" on May 28.

"We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills," he declared. "We shall never surrender."

That speech actually happened June 4, 1940.

The movie also fudges a few details. The king didn’t stop by to see Churchill in the middle of the night, and it wasn’t Churchill’s idea to launch a small boat brigade. Nevertheless, the movie does capture well Churchill’s willingness to fight Hitler with everything he had. Read our full analysis.

The movie Dunkirk, interestingly, gives a more focused look at some of the same events as Darkest Hour. The bulk of the British Army, well over 300,000 men, were surrounded on the beaches of Dunkirk, France, and about to be decimated by the German military. Back home, British leadership were intent on getting the men home.

Dunkirk doesn’t aim to give a history lesson so much as it seeks to dramatize a historical moment through a handful of invented characters. We found that the movie exaggerated a few aspects of the drama — it exaggerates the role of small boats, and suggests that Britain restrained its air force more than it did — but mostly Dunkirk sticks to accurate history. Read our full analysis.

Finally, The Post tells the story of two newspaper executives — the trailblazing publisher Katharine Graham, played by Meryl Streep, and the hard-charging editor Ben Bradlee, played by Tom Hanks — who decide to defy the federal government in order to inform the public about the truth behind the Vietnam War.

We found that The Post heightened the tension by exaggerating some of the negative reactions of key players, especially President Richard Nixon and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, to the release of the Pentagon Papers, a secret history of the events in Vietnam. Nixon at first saw the papers as reflecting more poorly on his predecessors, while McNamara grudgingly accepted the release.

The Post also underplays the role of leakers in at least two key aspects. The movie suggests that a Post journalist ferreted out the Pentagon Papers. But firsthand accounts credit the leakers with contacting the newspaper. When other newspapers around the country started publishing the papers, it was because the leakers had reached out to them, not because the papers were following the courageous lead of the Post. Read our full analysis.

Finally, The Post suggests that Bradlee had regrets about his too-cozy relationship with President John F. Kennedy. In real life, Bradlee seemed pleased with the balancing act he negotiated.

"In a matter of days I had felt comfortable with Kennedy," Bradlee wrote in his memoirs, "sure that he instinctively understood the complicated perimeters of our friendship and the conflict between friendship and journalism."

Our Sources

See individual stories for sources.