Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

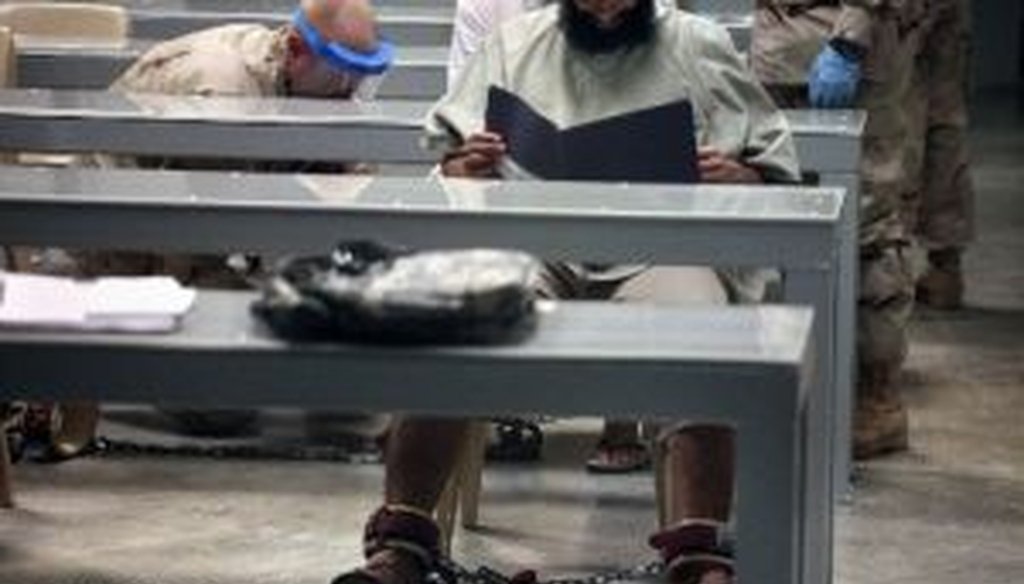

This 2010 photograph, made through one-way glass and reviewed by the U.S. military, shows a shackled Guantanamo detainee reading his materials in a "Life Skills" class as guards behind him shackle another detainee to the floor after bringing him to class.

The release of Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl in exchange for five Taliban detainees from Guantanamo is shining a spotlight on what will ultimately happen to the United States’ prison camp in Cuba.

Some public officials and commentators have suggested that getting Bergdahl back may have been a good idea if the United States were forced to close Guantanamo once the last American troops leave Afghanistan, now slated for 2016. If the Taliban detainees were eventually approaching release anyway, the argument goes, the United States might as well get something in exchange while it can -- in this case, Bergdahl’s freedom.

For instance, Fox News contributor Geraldo Rivera posted the following on his Facebook page:

"The age-old law of war says POWs are exchanged once hostilities cease. We are ending the War in Afghanistan in a few months. Guantanamo Prison Camp must be closed at that time if we are to be in compliance with centuries of law and custom. In other words, the prisoners in Guantanamo will be released regardless, so to give back five of them now as opposed to next year is merely a question of timing." (Rivera also tweeted a similar point.)

Other commentators disagreed, saying there’s no reason to say the Taliban detainees are close to being repatriated.

In an interview with Fox News, Sen. Lindsey Graham , R-S.C., called it an "absurd idea."

The notion "that the day we withdraw from Afghanistan is the end of hostilities and we have no legal authority to hold these people at Gitmo is just flat wrong. The hostilities we're engaged in is not against the Afghan government or people. It's against terrorist organizations and those who provide material support."

We thought we’d take a closer look at what international law says about the closure of Guantanamo once the war in Afghanistan is over, particularly the question of whether the prison camp "must be closed," as Rivera put it. However, because international law is subject to varying interpretations, we won’t put any of the claims on the Truth-O-Meter.

Indeed, each of the experts we contacted began by noting that this question delved into murky territory, on several levels.

"The scope of the authority to detain, including its duration, is immensely complex," said Steven R. Ratner, University of Michigan law professor.

The first thing to note is that the Guantanamo detainees include alleged members of two different groups -- al-Qaida and the Taliban -- and there’s a case to be made that the two types of prisoners qualify for different levels of protection under international conventions.

Article 118 of the Geneva Convention, which covers the treatment of military personnel, says that "prisoners of war shall be released and repatriated without delay after the cessation of active hostilities." Taliban detainees would seem to have a better argument for being repatriated following the end of hostilities in Afghanistan than detainees of al-Qaida.

"Afghanistan is a party to the Geneva Conventions, and the Taliban represented the nation’s de facto government," said Richard D. Rosen, a retired Army colonel who now directs the Center for Military Law and Policy at Texas Tech University. Indeed, the United States’ decision under President George W. Bush to treat the Taliban as unlawful combatants not qualifying for the Geneva Convention’s protections was controversial partly for these reasons.

By contrast, al-Qaida is a non-state actor, and thus it’s easier to make the case that its members aren’t covered by the Geneva Convention and its provisions on post-war repatriation.

"Once hostilities are over, we have an obligation to release the Taliban detainees, but not the al-Qaida detainees, and perhaps not those members of the Taliban who are affiliated with al-Qaida," Rosen said.

That said, the United States may have some wiggle room -- if it wishes to take it -- on declining to release Taliban detainees any time soon.

"When we are talking about a ‘war on terror,’ as opposed to an armed conflict among states, how do you determine when active hostilities have ceased?" said Anthony Clark Arend, Georgetown University professor of government and foreign service. "Where there is an ongoing conflict with non-state actors that will likely continue even if U.S. forces leave Afghanistan, it is difficult to say that hostilities have really ended."

Lance Janda, a military historian at Cameron University, agreed that there’s some gray area.

Whether the Geneva Convention’s provisions on releasing prisoners applies to the war in Afghanistan "is an open question," Janda said. Among other things, "the United States did not declare war, and we have always maintained that the captured terrorists are not prisoners of war under international law and so therefore we are not obligated to treat them according to the Geneva Convention."

There’s another reason to be doubtful that such a closure would be forced on the United States any time soon. Article 119 of the Geneva Convention says, "Prisoners of war against whom criminal proceedings for an indictable offence are pending may be detained until the end of such proceedings, and, if necessary, until the completion of the punishment. The same shall apply to, prisoners of war already convicted for an indictable offence."

In other words, Rosen said, "if we intend to try any of the Taliban detainees for war crimes, or other offenses, we need not release them." This presents an additional reason to need Guantanamo to remain open beyond the end of hostilities in Afghanistan.

So, while there’s ample precedent in history and international law for post-war prisoner exchanges, there are plausible arguments to be made that al-Qaida detainees, and perhaps even Taliban detainees, would not automatically qualify to be sent home once hostilities in Afghanistan end. This would make the notion of a looming, automatic closure of Guantanamo premature at best, and incorrect at worst.

That said, not being forced by international agreements to close Guantanamo doesn’t mean we shouldn’t consider moving in that direction on our own, Janda said.

"As a practical matter, we ought to be thinking about an endgame, and about how and when and if we release the remaining prisoners in Guantanamo," he said. "But those decisions will be driven by politics and national security issues rather than international obligation."

Indeed, international agreements provide only limited advice on this question. The Geneva Convention doesn’t say what a detaining state must do with detained people who are not prisoners of war or civilians, "probably because it didn't contemplate another category," Ratner said.

"It's not even clear that the U.S. is at war with Afghanistan at all -- after all, since the fall of the Taliban in late 2001, U.S. forces have been there with the Afghan government's permission, so how can the U.S. be at war with Afghanistan?" Ratner said. "Really, the U.S. is helping Afghanistan with an internal conflict with the Taliban, and the rules on detention in internal conflict are few and far between."

Arend agrees that there’s a "lacuna," or void, in the Geneva Convention regarding the types of detainees held at Guantanamo.

"Does that mean that detainees can be held indefinitely?" Arend said. "The Geneva framework doesn't really answer that question. This is one reason why I believe we desperately need a new Geneva Convention to address non-state actors and terrorism."

Our Sources

Geraldo Rivera, Facebook post, June 5, 2014

Geraldo Rivera, tweet, June 5, 2014

Lindsey Graham, interview on Fox News, June 4, 2014

Reuters, "Obama plans to end U.S. troop presence in Afghanistan by 2016," May 27, 2014

Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, entered into force Oct. 21, 1950

Email interview with Anthony Clark Arend, Georgetown University professor of government and foreign service, June 6, 2014

Email interview with Richard D. Rosen, director of the Center for Military Law and Policy at Texas Tech University, June 6, 2014

Email interview with Lance Janda, military historian at Cameron University, June 6, 2014

Email interview with Steven R. Ratner, University of Michigan law professor, June 6, 2014