Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

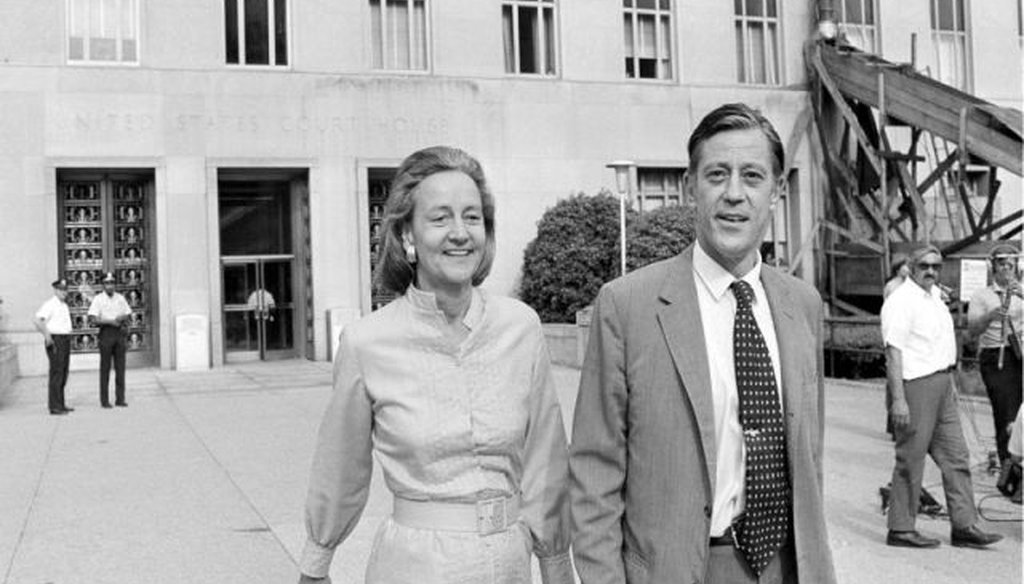

In this June 21, 1971 file photo, Washington Post Executive Director Ben Bradlee and Post Publisher Katharine Graham leave U.S. District Court in Washington (AP Photo, File).

Editor's note: Have you ever wondered if the movie you just saw — that claimed to be based on a real story or historical events — was really accurate? So have we. With this year’s Oscars featuring historically based movies up for honors, we wanted to help you sort out the facts from the dramatic liberties. (We've also factchecked Darkest Hour and Dunkirk.) Warning, major spoilers and plot points ahead!

The Post, Steven Spielberg’s paean to the First Amendment and the free press, tells the tale of the Washington Post’s diffident publisher and ambitious editor summoning the courage to publish a top-secret study in the face of unprecedented government censorship.

The action begins when a disillusioned Vietnam War supporter-turned-dove absconds with a 7,000-page classified study of the U.S. war effort that exposed the misleading nature of the government’s optimistic public assessments over more than two decades.

The leak of this secret history, later dubbed the Pentagon Papers, to the New York Times touches off a media arms race with the up-and-coming Washington Post. The masthead’s gamble helped the Post grow into one of political journalism’s most formidable watchdogs.

Here’s what’s accurate about the movie, and what’s not.

In the film, Washington Post national editor Ben Bagdikian (played by Bob Odenkirk) gets a hunch that the New York Times’ source is Daniel Ellsberg, his former colleague at the defense contractor Rand. The film credits Bagdikian’s gritty journalistic legwork with ultimately leading the Post to Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers.

But the memoirs of Bagdikian and Ellsberg put more emphasis on the Pentagon Papers finding the Post, rather than the other way around.

According to Bagdikian’s account, days before the Times’ bombshell report, he heard rumors that the secretive reporting project "had something to do with an exclusive report from Rand."

"I called Henry Rowen, the president of Rand. He said he knew nothing of the sort," Bagdikian wrote in his 1995 memoir Double Vision: Reflections on My Heritage, Life, and Profession.

A few days later, Bagdikian writes, he got a message from an intermediary who connected him to Ellsberg. He makes no mention of doggedly pursuing Ellsberg, as portrayed in the film.

Used with permission from Fox Entertainment Group (Credit: Niko Tavernise).

Ellsberg wrote in his memoir that he sought out Bagdikian, though he says the editor had been looking for him.

"I went to a pay phone and made arrangements through a friend to call Ben Bagdikian at the Washington Post," Ellsberg wrote in his 2002 memoir. "I took it for granted he would be hunting for a way to get a piece of the papers; I guessed, correctly, that he would already suspect that I was the source and was probably trying to find me."

However, two accounts largely back up the sequence depicted in the film. One is Post publisher Katharine Graham, who recalled in her 1997 memoir Personal History that Bagdikian "had guessed that Daniel Ellsberg was the source for them at the Times, and he had been frantically calling Ellsberg." (Meryl Streep is nominated for Best Actress for her portrayal of Graham.)

The second is an inside account written in 1972 by Sanford Ungar, a former Post reporter whose 16,000-plus word narrative credits Bagdikian for following his hunch about Ellsberg with several unreturned phone calls and messages. "That evening, Bagdikian was phoned by a friend of Ellsberg’s, who would not speak in much detail until Bagdikian called him back from a pay telephone," Ungar wrote.

Used with permission from Fox Entertainment Group (Credit: Niko Tavernise).

Ultimately, securing an injunction against publishing the Pentagon Papers was President Richard Nixon’s decision. What the film doesn’t show is he was initially sanguine about publication.

In the film, the first time we see Nixon react to the Pentagon Papers is during an conversation between the president and Deputy National Security Adviser Alexander Haig. (Yes, the tape we hear is authentic.)

Haig describes the coverage as a "New York Times exposé of the most highly classified documents of the war." He later continues, "There’s a whole study that was done for McNamara. This is a devastating security breach of the greatest magnitude of anything I’ve ever seen."

Initially, however, Nixon dismissed the story because it uncovered misconduct only by previous, mostly Democratic, administrations, said Mark Feldstein, who authored Poisoning the Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington's Scandal Culture.

Nixon told his staff that publication of the papers "doesn’t hurt us," so "the key is for us to keep out of it," according to Feldstein. It was only after he talked to Haig and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger that his thinking about the Pentagon Papers took on the paranoid, vindictive complexion that would eventually culminate in a Supreme Court decision in the papers’ favor.

"Haig persuaded Nixon that publication really did threaten national security and Nixon went into one of his anti-press downward spirals that Kissinger then reinforced," Feldstein said. "Nixon reversed course and decided that the leak was ‘unconscionable,’ a ‘treasonable action on the part of the bastards that put it out.’"

In the film, Graham’s friend Robert McNamara, the former Secretary of Defense who commissioned the Pentagon Papers, pleads with Graham not to publish:

"The study was for posterity. It was written for academics in the future and right now, we’re still in the middle of the war, the papers can’t be objective. And I suppose the public has a right to know, but I would prefer that the study not be made widely available until it can be read with some perspective."

We couldn’t find any record of that conversation happening.

In a Nov. 17, 1961 file photo, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara holds a news conference at the Pentagon. (AP Photo/Harvey Georges, File)

According to Graham’s memoir, McNamara actually encouraged the New York Times to go ahead with publishing despite his "distaste for the early publication of these documents." Graham also said McNamara advised the Times to change the wording of their response to the government’s cease-and-desist letter to circumscribe the government's ability to limit the Times' free speech.

McNamara’s own memoir corroborates this. He writes that he was "tangentially involved behind the scenes," before echoing Graham’s account.

"I said the Times should continue printing them but should hedge its position by making clear it would obey any order issued by the Supreme Court," as opposed to any court, McNamara wrote.

It strains credulity that McNamara would encourage the Times to run the Pentagon Papers — and even take efforts to help shield them from undue government interference — and then pressure the Post not to publish.

Historians noted this scenario seems even less likely given McNamara’s pessimistic view of the Vietnam War at the time of the Pentagon Papers leak.

"I doubt very much that he discouraged her," said Fredrik Logevall, professor of history at Harvard University and expert on U.S. foreign policy and the Vietnam War. "McNamara was more skeptical in private about the war at an earlier point than this film suggests."

Used with permission from Fox Entertainment Group (Credit: Niko Tavernise).

In one pivotal scene, editor Ben Bradlee (played by Tom Hanks) expresses regret for maintaining a cozy personal relationship with President John F. Kennedy while covering him as a journalist.

"I never thought of Jack as a source," Bradlee tells Graham. "I thought of him as a friend. And that was my mistake."

Bradlee’s complicated relationship to Kennedy remains a hotly debated aspect of his legacy. It also doesn’t lend itself to the film’s tidy storyline.

Used with permission from Fox Entertainment Group (Credit: Niko Tavernise).

In the film, Bradlee’s desire to atone for a breach of journalistic ethics during the Kennedy administration bolsters his commitment to hold accountable both the subjects of the Pentagon Papers, which included the Kennedy White House, as well as the Nixon administration that sought to keep these long-held secrets under wraps.

It’s certainly possible Bradlee privately expressed misgivings about his coverage of Kennedy. But his written accounts of their relationship conveyed a mixed bag.

In 1975, 11 years after Kennedy’s assassination, Bradlee published Conversations with Kennedy, a behind-the-scenes look at the former president. A review in the New York Times noted that Bradlee repeatedly described finding himself in hot water with the president over critical coverage.

"He mentions a goodly number of times — almost as a mea culpa — that his reporter's instincts usually got the better of him and he filed stories in Newsweek sufficiently unflattering to the Kennedy Administration to earn the President's salty verbal castigation or temporary social banishment," the review states.

President John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy with Mr. & Mrs. Benjamin C. Bradlee on May 29, 1963. White House, Family Living Room. Photograph by Cecil Stoughton, White House, in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Twenty years later, Bradlee published a personal memoir, A Good Life, in which he revisited the relationship:

"The experience of having a friend run for President of the United States is unexpected, fascinating, and exciting for anyone. For a newspaperman it is all that, plus confusing: are you a friend, or are you a reporter? You have to redefine ‘friend’ and redefine ‘reporter' over and over again, before reaching any kind of comfort level. And that takes time, before you get it right."

At other points in his memoir, Bradlee seems to suggests he and Kennedy established a modus vivendi, despite the initially confusing arrangement.

"In a matter of days I had felt comfortable with Kennedy," he writes, "sure that he instinctively understood the complicated perimeters of our friendship and the conflict between friendship and journalism."

Near the end of the film, Bradlee triumphantly marches into Graham’s office, clears off her desk, pulls newspapers from a brown bag and throws them down one at a time: the St. Louis Post Dispatch, the Boston Globe, the Christian Science Monitor.

"They all followed your lead and published the papers," Bradlee proudly tells Graham.

But the film ignores that publication of the Pentagon Papers played out according to a distribution plan hatched by Ellsberg and his co-conspirator. Ellsberg’s memoir also undercuts the notion that other newspapers took their cue from the Post.

"Nearly every major paper wanted to get in on the action — impressively, given the unprecedented legal actions and evident fury of the administration — and not one we approached turned down the opportunity," Ellsberg wrote.

In this Jan. 17 1973 file picture, Daniel Ellsberg speaks to reporters outside the Federal Building in Los Angeles. (AP Photo)

Ellsberg recalled that after the Post was enjoined from publishing the Pentagon Papers, he wanted "to dump the rest of it out to a number of papers at once, to make sure it all got out before I was stopped."

But his co-conspirator Gar Alperovitz, drawing on his earlier experience working for a member of Congress, persuaded Ellsberg that it would be better to approach subsequent papers one a time to keep the story in the news cycle.

Ellsberg explains how he selected each paper, sometimes based on idiosyncratic reasons:

"After the Washington Post was enjoined, the Boston Globe was an obvious choice for the next recipient, not so much because it was our local paper as because it had been one of the first and strongest to oppose the war. That was also true of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, which I thought had earned the right to invite an injunction. It received one, along with the Globe. (...) Others I picked on more idiosyncratic grounds. The L.A. Times, which I thought had also done good reporting on the war, was my former hometown newspaper; the Knight chain of eleven newspapers included my father’s town of Detroit; and the Christian Science Monitor was my father’s main paper (he sent me subscriptions to it for many years)."

This doesn’t take away from the courage the Post showed in deciding to publish. But it suggests that other newspapers took that courageous decision independent of the Post, and according to Alperovitz’s rollout plan, as opposed to following the Post’s lead.

Katherine Graham, publisher of the Washington Post, and Executive Editors Benjamin C. Bradlee look over reports today of the 6 to 3 Supreme Court decision which permits the paper to publish stories based on the secret Pentagon study of the Vietnam War. 1971 (AP Photo/File)

Our Sources

"The Post," 20th Century Fox

Ben Bagdikian memoir, Double Vision: Reflections on My Heritage, Life, and Profession, 1995

Daniel Ellsberg memoir, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers, 2002

Katharine Graham memoir, Personal History, 1997

Sanford Ungar in Esquire, "The Papers Papers," May 1972

President Richard Nixon June 13, 1971 phone call with Deputy National Security Adviser Alexander Haig, YouTube

Ben Bradlee, Conversations with Kennedy, 1975

Ben Bradlee memoir A Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures, 1995

New York Times, "Conversations With Kennedy," May 11, 1975

The New Yorker, "The Untold Story of the Pentagon Papers Co-Conspirators," Jan. 29, 2018

Email interview with Mark Feldstein, journalism professor the University of Maryland and author of Poisoning the Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington's Scandal Culture, Feb. 7, 2018

Email interview with James Goodale, former vice president and general counsel for the New York Times, Feb. 8, 2018

Email interview with Floyd Abrams, co-counsel to the New York Times in the Pentagon Papers case, Feb. 7, 2018

Email interview with Fredrik Logevall, professor of history at Harvard University and expert on U.S. foreign policy and the Vietnam War, Feb. 7, 2018

Email interview with Leonard Downie, Jr., former executive editor at the Washington Post, Feb. 8, 2018

Interview with Todd Gitlin, professor of journalism at Columbia Journalism School, Feb. 6, 2018

Interview with Ben Bradlee, Jr., Feb. 12, 2018

PolitiFact Rating:

PolitiFact Rating: