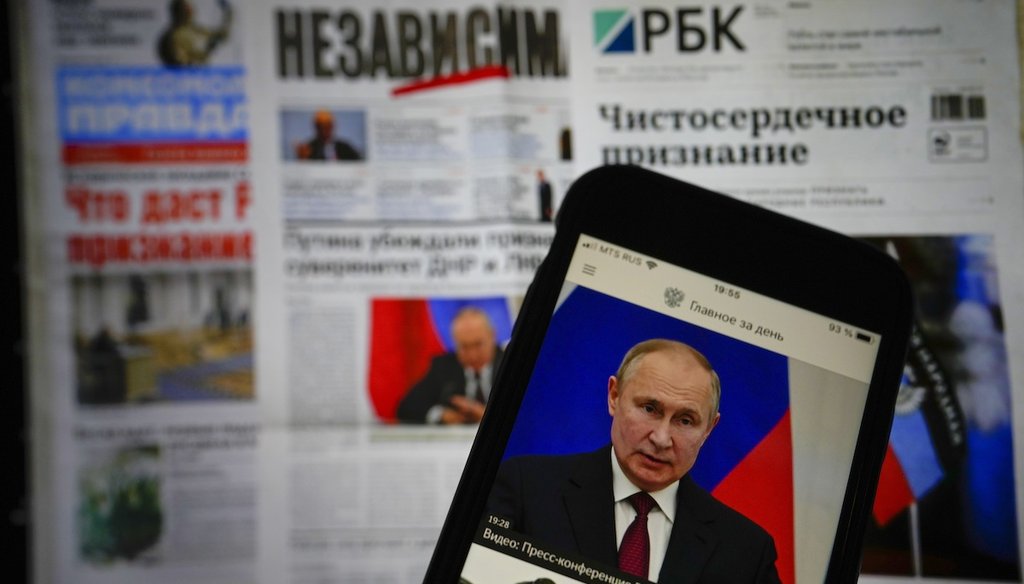

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russian state media present the attack on Ukraine as a rescue mission to stop the annihilation of ethnic Russians in Eastern Ukraine. (AP)

Despite multiple claims of a Ukrainian genocide against ethnic Russians, there is no evidence to support it.

International bodies that include Russian representatives report that civilian deaths have plummeted since 2014.

Russia’s ambassador to the U.S. relied on misleading and outdated evidence to back the claim.

Russia has given several reasons for launching a war against Ukraine. In a televised address announcing the military assault, President Vladimir Putin said the spread of NATO was a life or death matter. He blamed NATO for fostering governments along Russia’s border — in a region he called Russia’s "historical land" — that don’t like Russia.

But Putin also called Russia’s air and ground attacks across Ukraine a rescue mission "to protect people who, for eight years now, have been facing humiliation and genocide perpetrated by the Kyiv regime." "To this end," he said Feb. 24, "we will seek to demilitarize and de-Nazify Ukraine."

Putin has long said genocide was happening in the Donbas region of Eastern Ukraine. When gas supplies were interrupted in 2015, Putin said it "smells of genocide." In 2019, he predicted a mass slaughter of ethnic Russians there on the scale of Srebrenica, a massacre in the former Yugoslavia’s civil war, when Serbs slaughtered over 7,000 Muslim men and boys. In 2021, he said the conflict in Donbas "looks like genocide."

There is no evidence for claims of genocide. But invoking it gives Putin a pretext for the invasion.

If genocide were taking place, civilian deaths in Eastern Ukraine would be going up. According to the UN Commission on Human Rights, they have plummeted.

The count of victims went from 2,084 in 2014 to 18 in 2021. This isn’t a perfect measure. It includes all civilian deaths on both sides of the dividing line in the conflict zone. But deaths in the most recent period are more than 100 times less that at the start of the fighting in Eastern Ukraine.

It would be hard to hide a widespread program of violent ethnic repression. There are many observers on the ground. In addition to journalists and ordinary citizens with social media accounts, the Organization for Cooperation and Security in Europe conducts special monitoring in Eastern Ukraine. The group represents 57 nations, including Russia.

It produces daily reports of casualties, many of them due to landmines placed by both government and separatist forces. None of its reports show anything resembling genocide. There are more injuries and deaths due to mines in non-government controlled areas, but that could be due to mines placed by separatist forces.

In a Facebook post, Russia’s ambassador to the U.S. Anatoly Antonov defended the use of the term genocide, citing Ukrainian forces shelling residential neighborhoods and "mass burials of almost 300 civilians near Luhansk, who died just because they thought Russian was their native language."

Ukrainian shells have killed civilians, but so have munitions fired by Russian separatists. As noted above, the death toll has declined greatly, and in many cases, it is difficult to know who fired a specific artillery round.

Antonov’s reference to mass burials in Luhansk is particularly misleading. That city was the center of some of the most intense fighting in 2014, the first year of the war, before any sort of ceasefire was negotiated. Both Ukrainian and Russian speaking people died.

A man walks outside a house damaged by shelling in Luhansk, eastern Ukraine, as fighting flared between separatists and government troops (AP/2014 file photo)

By the time a tenuous truce took hold, over 500 people had been killed. The coffins accumulated so quickly that they were placed in a long trench. They were deaths of war, not the victims of an organized massacre, as Antonov’s words might suggest.

By no stretch of the imagination does anything in Ukrainian law or practice meet the international definition of genocide. The convention on genocide forbids five acts:

Killing members of the group;

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Ukraine’s language and education laws have drawn criticism because they favor Ukrainian, but they fall well short of crossing the line into genocide.

Russian speakers can attend Russian language schools through the fourth grade. After that, courses must be taught in Ukrainian, except if they are about Russian literature or culture, in which case, they can be taught in Russian.

The rules governing language are not as favorable to Russian speakers. Ukrainian is the sole official language. Recently, the government began to enforce a rule that all books must include a Ukrainian language version. There’s no ban on publishing in Russian, but a companion Ukrainian version is also required, placing an additional cost on publishers.

Putin isn’t the first leader in the region to invoke genocide. It is a term that politicians have deployed loosely for rhetorical effect. Putin’s use now gives him — at least in theory — a two-for-one benefit. The rhetoric doesn’t just tie Ukraine to an act of extreme evil, it ties it to Nazism. And that, as Thomas de Waal at the Carnegie Institute for International Peace wrote in 2014, carries a special meaning in Russia.

"Antifascism has increasingly become a central idea in Putin’s Russia, reinforcing a growing tendency to identify the modern country with the Soviet Union," de Waal wrote. "The Red Army’s victory over Nazism is increasingly reframed as a victory of the Russian nation rather than of the multiethnic Soviet people."

Through the lens of genocide, Putin can tap into Russian patriotism, and argue that this attack is just and noble. Regardless of what the facts on the ground might be.

Putin said ethnic Russians in Ukraine face genocide.

His ambassador provided misleading evidence, and international observers found no activities to support the claim. Civilian deaths have plummeted to less than 1% of what they were in 2014.

We rate this False.

Bloomberg, Transcript: Putin address on Ukraine, Feb. 24, 2022

Office of the President of Russia, Address by the President of the Russian Federation, Feb. 21, 2022

United Nations Commission on Human Rights, Conflict-related civilian casualties in Ukraine as of 8 October 2021, Oct. 8, 2021

Organization for Cooperation and Security in Europe, Daily and spot reports from the Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine, accessed Feb. 23, 2022

Organization for Cooperation and Security in Europe, The impact of mines, unexploded ordnance and other explosive objects on civilians November 2019 – March 2021, May 2021

U.S. Mission to OCSE, tweet, Feb. 16, 2022

Council on Foreign Relations, Conflict tracker: Ukraine, Feb. 22, 2022

Embassy of Russia in the U.S., Facebook post, Feb. 17, 2022

The Guardian, Despair in Luhansk as residents count the dead, Sept. 11, 2014

United Nations, Genocide, accessed Feb. 24, 2022

German Institute for International and Security Affairs, The Donbas Conflict, 2019

OECD, Ukraine, October 2016

BBC, Putin compares Donbas war zone to genocide, Dec. 10, 2021

International Crisis Group, Conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas: A Visual Explainer, Dec. 31, 2021

Human Rights Watch, Crimea: ‘Not Our Home Anymore’, May 3, 2017

EuroNews, Kyiv's suspension of gas flow to eastern Ukraine 'smells of genocide' says Putin, Feb. 25, 2015

Reuters, Putin warns of second Srebrenica if no amnesty for east Ukraine, Dec. 10, 2019

RTE, Putin says conflict in eastern Ukraine 'looks like genocide', Dec. 9, 2021

The Guardian, UN Security Council meeting, Feb. 17, 2022

Al-Jazeera, ‘They shoot, we hide’: Life amid shelling on Ukraine’s front line, Feb. 20, 2022

Law of Ukraine, Indigenous people, July 1, 2021

Culturico, The Law on the Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine. What does it bring to national minorities?, Dec. 20, 2021

Embassy of Ukraine in Hungary, Explanation on the Law of Ukraine "On ensuring the functioning of the Ukrainian language as the state language", May 16, 2019Radio Free Europe, Language Law For National Print Media Comes Into Force In Ukraine, Jan. 16, 2022

Open Democracy, Beyond the scandal: what is Ukraine’s new education law really about?, Dec. 8, 2017

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Crying Genocide: Use and Abuse of Political Rhetoric in Russia and Ukraine, July 28, 2014

Atlantic Council, Putin’s absurd genocide claims cannot hide his war crimes in Ukraine, Feb. 18, 2022

New York Times, Putin’s Baseless Claims of Genocide Hint at More Than War, Feb. 19, 2022

In a world of wild talk and fake news, help us stand up for the facts.