Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

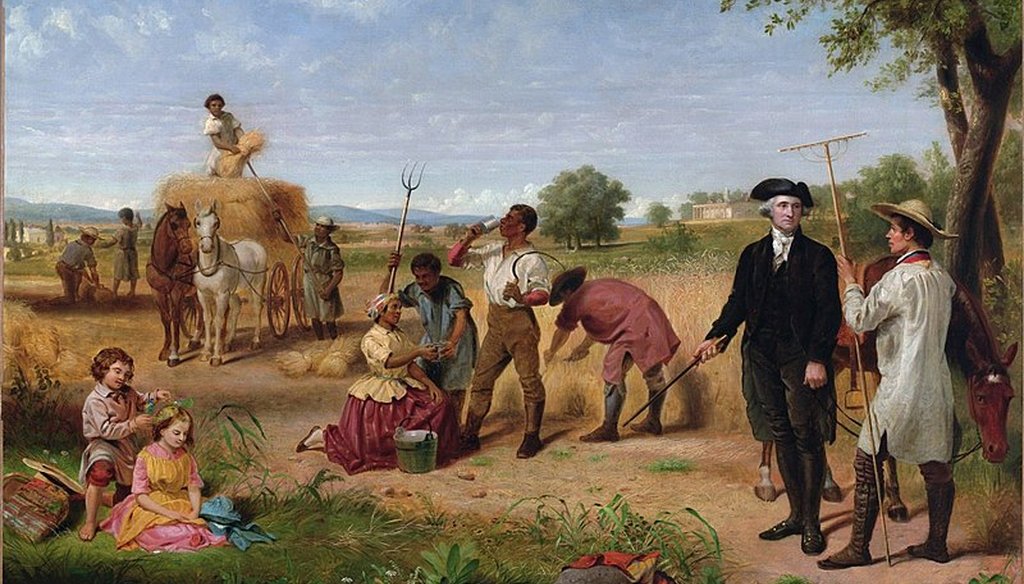

"Washington as Farmer at Mount Vernon," part of a series by Junius Brutus Stearns, 1851

President Donald Trump said a precedent exists for an active businessman like himself serving as president -- his legendary first predecessor, George Washington.

Trump’s remark came in response to a reporter’s question about the G-7 meeting, which Trump had recently backed off hosting at his Trump National Doral property amid concerns that he could financially benefit from it.

The G-7 dispute was the latest in a line of controversies about whether Trump properties stand to benefit either from federal government largesse or from foreign payments.

During a lengthy media availability on Oct. 21, Trump said, "I don’t know if you know it, George Washington, he ran his business simultaneously while he was president."

When we asked the Trump campaign for evidence to support this claim, they pointed us to some of the arguments being made in court that the Trump properties aren’t covered by the Constitution’s emoluments clause. We also spoke to one of the authors of some of those briefs.

Ultimately, we found conflicting interpretations of Washington’s activities as a businessman during his tenure as president. This evidence is heavily dependent on one’s definition of "business."

Mount Vernon mansion, eastern facade. (Wikimedia commons)

There’s no question that Mount Vernon, Washington’s plantation, was an ongoing business concern during his presidency.

"As president, Washington kept a close watch over his plantation, mainly through frequent correspondence with his farm managers," said Henry Wiencek, author of "An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America."

Historian Joseph. J. Ellis, who spent years reviewing Washington’s papers and authored "His Excellency: George Washington," agreed. "He was preoccupied with Mount Vernon," Ellis told PolitiFact.

It’s conceivable that Washington could have sold agricultural goods to the government or to foreign entities, though solid documentation of it doesn’t appear to exist, said Josh Blackman, a law professor at the South Texas College of Law in Houston who has authored briefs in support of the Trump administration’s position on emoluments cases.

But even if such purchases had been made, Ellis and Wiencek agreed that Mount Vernon was a multifaceted enterprise.

"It’s not just his business — it’s his home," Ellis said.

Indeed, comparisons between the late 18th century and the 21st century are tricky, since politics was not a career that could support a family without a primary line of work. Most politicians at the time would have needed an alternative income beyond politics or government.

Lock 1 of the Patowmack canal. (National Park Service)

Washington, a surveyor by training, had a longstanding interest in real estate. Most of his landholdings were west of the Appalachian Mountains and largely unsettled, making them relatively unfavorable for development in the late 1700s.

In 1785, about four years before Washington became president, the Virginia House of Delegates chartered the Patowmack Company, which would build canals that could service those areas and make the Potomac River valley more commercially viable.

Washington invested 2,400 pounds in the effort, said Joel Achenbach, author of the 2004 book, "The Grand Idea: George Washington's Potomac and the Rise of the West." (The Virginia pound was a state currency in use at the time.) Washington held these shares through his death, at which point he directed that they help establish a national university. As for his landholdings, Washington left nearly 50,000 acres to his heirs.

So Washington clearly had a financial interest in the company’s success while serving as president. However, it was something of a passive interest with a long time horizon, rather than something requiring active management during his presidency.

Achenbach considers it a labor of love and a money sink: It took 17 years to bear any fruit.

"It was hardly a business," Achenbach told PolitiFact. "The canal didn’t go into operation until after Washington was dead. They had a terrible time blasting out the bedrock at Great Falls. It was a money loser and was eventually abandoned in favor of the C&O Canal.

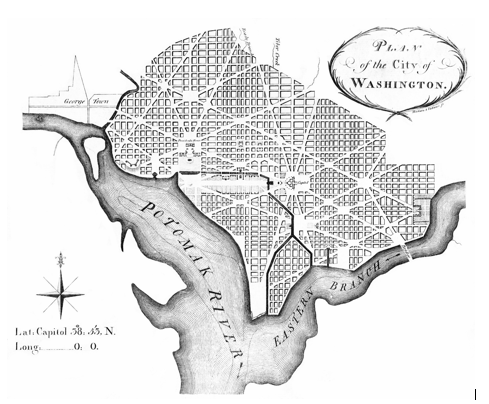

L'enfant's plan of the city of Washington, March 1792.

The future city of Washington, D.C., was created when Congress passed a law designating the seat of government there on July 16, 1790.

Washington served as president before the city that would bear his name was built. Washington spent 16 months as president in New York City, followed by six and a half years in Philadelphia. After spending his first three years in Philadelphia, the second president, John Adams, moved into the newly constructed White House in 1800.

Between the capital’s legal creation and Adams’ move into the White House came a variety of federal efforts to build out the new city. As part of that, President Washington bought four lots of land in the new capital in an auction on Sept. 18, 1793.

As a large, longstanding landholder, Washington "was purchasing land that could be used for private purposes" at that auction, Blackman said.

Achenbach said these transactions could "plausibly be seen as just trying to get the town — later named after him — up and running."

Of course, the first president was already deeply enmeshed in the city’s creation, having signed the legislation to place the future capital in a place not far from his own home base at Mount Vernon.

Such cross-cutting allegiances were not uncommon in the United States’ early days, when new infrastructure was being weighed and when some of the most likely beneficiaries had a foot in both the business and political worlds.

In the book "Building the Empire State: Political Economy in the Early Republic," Baruch College historian Brian Murphy wrote that such "political entrepreneurs" as Aaron Burr, DeWitt and George Clinton, Robert Fulton, Alexander Hamilton, and Robert Livingston blurred the lines between politics and business.

Overall, they saw government’s role as spurring the development of economic activity, but doing it in a way that was both efficient and in the best interests of the country.

"Creating a dynamic marketplace required the interposition of state power, and in the view of this cohort, the state was supposed to be actively aiding the ambitions of the ambitious; for them, the controversy most often concerned whose enterprising plans merited support," Murphy wrote.

CLARIFICATION, Oct. 31, 2019: This version clarifies the fate of Washington’s Patowmack Co. shares. Washington’s wish that his shares go towards establishing a national university didn’t materialize, but he did bequeath a separate batch of 100 shares he held in the James River Canal Co. to expand the university now known as Washington & Lee.

Our Sources

Donald Trump, remarks in a cabinet meeting, Oct. 21, 2019

Joel Achenbach, "The Grand Idea: George Washington's Potomac and the Rise of the West," 2004

White House Historical Association, "Introduction: Where Oh Where Should the Capital Be?" accessed Oct. 29, 2019

The Volokh Conspiracy, "Who Was Right About the Emoluments Clauses? Judge Messitte or President Washington?" Aug. 3, 2018

Bloomberg View, "George Washington Had Business Interests, Too," Nov. 25, 2016

Email interview with Henry Wiencek, author of "An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America," Oct. 22, 2019

Email interview with Joel Achenbach, "The Grand Idea: George Washington's Potomac and the Rise of the West," Oct. 23, 2019

Interview with Josh Blackman, law professor at the South Texas College of Law, Oct. 22, 2019

Interview with Joseph. J. Ellis, author of "His Excellency: George Washington," Oct. 22, 2019