Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Ad services that serve up clickbait content known as "chum" may look legitimate at first, but are actually generating money for fake news sites like DailyNews10.com.

Robert Shooltz knows that fake news can lead to real money.

He runs RealNewsRightNow.com, a website that parodies real news outlets by running absurd posts written to read like factual articles. Working online in his off hours, he uses the site to generate advertising revenue.

In an average month, he said, his side hustle can net him about $1,000 a month. It’s not much, but it pays for server space and site promotion, to bring in more readers.

"At this point it’s still a side venture and definitely not enough to live off of, but the goal is to get to a point where I can write full time and support myself while doing so," Shooltz told PolitiFact.

Some fake news purveyors claim to make big bucks from their faux wares.

Paris Wade and Ben Goldman, the two men behind the fake news site LibertyWriters.com, said they made up to $40,000 per month in the runup to the 2016 presidential election.

Cameron Harris, a Davidson College grad looking to pay back his student loans, said he managed to clear more than $1,000 an hour from his short-lived ChristianTimesNewspaper website.

Those fake news-selling teenagers in Macedonia said they raked in tens of thousands of dollars building slipshod sites filled with fake political news.

To do it: All you need are some common online services and enough tech savvy to set up your own website.

As more fake news websites pop up, though, they’re facing attempts by major ad companies to interrupt their flow of money.

Pretty much any website — not just the fake ones — that wants to make money has some different options for selling advertising. In this article, we’re going to focus on two: advertising networks and sponsored content.

In simplest terms, advertising networks are third parties that connect advertisers with website publishers. Shooltz used Google AdSense, but there are scads of other services.

The publisher gets to have a broad say in what categories or types of ads would appear, but overall the network decides what specific ad shows up. Advertisers, meanwhile, negotiate with the network on an amount they’ll pay if someone clicks on their ad. That amount is often measured in fractions of a cent per click.

If a reader on the publisher’s website clicks an ad, that advertiser will pay the network. The network then shares some of the revenue with the publisher.

It can take time to accrue advertising revenue that way, but multiply the scenario thousands of times and it can add up.

Also ubiquitous are sponsored content companies, which are a little different than ad networks.

Sponsored content services work on roughly the same principle of attracting clicks to pay publishers, using native advertising. (That’s when the ads resemble news stories, but aren’t.)

You’ve no doubt seen the telltale grid of hotlinked boxes sponsored content companies add to websites. The boxes are designed to attract your attention, sometimes by being salacious, titillating or even downright gross.

Here’s an example from a sponsored content vendor called Revcontent, as seen on a fake news site called President45DonaldTrump.com:

Similar to an ad network, a website publisher will agree to put code from a sponsored content service on their website, and the grid will appear on the website in a designated spot.

But instead of ads, these grids goad you into following a chain of often pointless stories (referred to as chum) designed only to draw clicks to other pages (and their ads). If a reader does that, the sites advertised on the grids pay the sponsored content vendor, which gives a percentage to the publisher of the original website that contained the code.

What fake news publishers found out is that it doesn’t matter if the original content is real or not, as long as readers flock to the site and start clicking.

The flow of ad dollars has been stanched a bit since the fake news outbreak during the 2016 election. Pressured to act, some companies have since set limits on which sites can use their ad services.

Google announced in November that sites that misrepresent themselves would no longer be able to use AdSense.

Facebook said the same month that fake news sites would not be able to use the Facebook Audience Network. A spokeswoman also pointed out to us that if a fake news story is flagged as disputed by Facebook’s fact-checking partners, which includes PolitiFact, an advertiser cannot create a Facebook ad that directs to that piece of content.

Some sponsored content services have policies that are supposed to limit fake news sites’ access, too. Katherine McDermott, a spokeswoman for Revcontent, said that sites that publish "any non-satirical political news which is demonstrably false or which is meant to intentionally deceive a consumer" don’t comply with the company’s policies.

Revcontent denies 94 percent of the websites who want to act as publishers, she said. Readers also can report fake news to the company as part of Revcontent’s Truth In Media Initiative, which the company announced in June.

If the goal is to prevent fake news sites from making money, however, there still is plenty of room for improvement.

Danny Rogers is the founder of Veracity.ai, which aims to help create a way for software to tell whether a website is a fake news publisher. He’s working with two companies called Storyful and Moat on a project called the Open Brand Safety framework.

The goal of the framework is to help inform advertisers about online content, and create a master list of fake news websites that advertisers would want to avoid. Rogers has used PolitiFact’s own Fake News Almanac to help jumpstart the research.

If advertisers know a site is filled with fake content, they’ll likely avoid placing ads on it. The services and advertisers willing to work with those sites may dwindle so much that it would choke off the windfall fake news has enjoyed.

"(These sites are) moneymakers, some of them making something like $40,000 a month using these services," Rogers said. "We want to start blocking them to make a dent in the money."

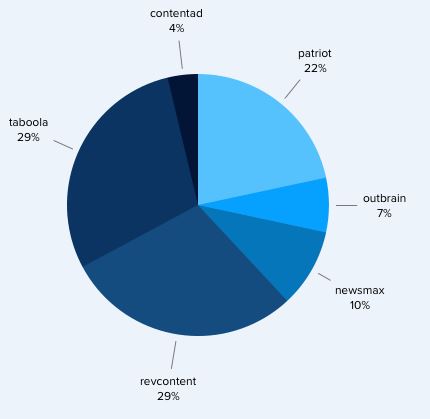

But even if sponsored content services have policies to try to avoid manufactured content, Rogers said, they still prop up many fake news websites. He looked at 1,076 domains for "mis- and dis-infomation sites" and found that they were going strong, thanks to sponsored content services

Revcontent and another service, Taboola, each appeared on about 29 percent of the fake news sites.

Content recommendation services across 1,076 mis-and dis-information sites

RealNewsRightNow.com, the site run by Shooltz, toes the line between satire and fake news. He says the content’s absurdity should make it obvious the stories are fake.

But RealNewsRightNow.com doesn’t carry a disclaimer pointing out the content is fictional. With all these efforts to blacklist fake news sites, an ad service could still decide his website doesn’t comply with its rules, or advertisers could opt out of his site, cutting off his cash flow.

If that happened, Shooltz said, he’d still keep his site going, but mostly because he views RealNewsRightNow.com as a creative writing exercise and not a moneymaking venture. If his advertising revenue was taken away, he’d still feel the effects, however minor.

"If I lost the ability to make money through advertising I'd likely have to scale back on promoting my articles through social media," he said. "But it wouldn't dissuade me from continuing to operate the site."

Our Sources

Sources are linked in the text.