Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

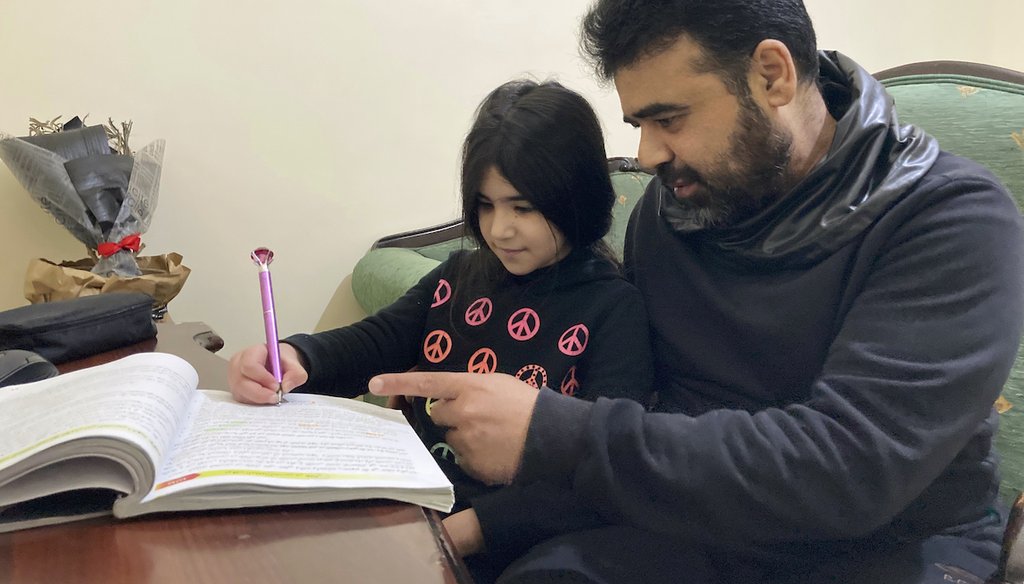

Syrian refugee Mahmoud Mansour, 47, with daughter Sahar, 8, at an apartment in Amman, Jordan, Jan. 20, 2021. Mansour's family had completed paperwork to go to the U.S. before the Trump administration halted the refugee program in 2017. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

The president, in consultation with Congress, determines the maximum number of refugees who can be allowed into the United States per fiscal year.

-

The Biden administration in February proposed admitting 62,500 refugees in fiscal 2021, up from the 15,000 set by the Trump administration.

-

In mid-April, the Biden administration said that admitting 62,500 refugees in fiscal 2021 was unlikely and that a final cap for 2021 would be announced by mid-May.

As a candidate for president, Joe Biden promised a very different approach to refugee admissions compared with President Donald Trump. Biden said he would increase the annual number of people let in as refugees, not decrease it as Trump did year after year.

So when Biden’s administration made an announcement April 16 that appeared to suggest that the cap on admissions for the current fiscal year would stay at the same level Trump ordered — 15,000 — it sparked confusion and anger among Democratic lawmakers and advocates for refugees. The human-rights group Amnesty International accused Biden of "turning his back" on refugees.

What exactly is going on?

The White House has since acknowledged that the April 16 announcement created confusion, and said it was not meant to be the last word on refugee admissions for the fiscal year. It said a final decision will come by mid-May.

But the administration’s clarification also signaled that it’s likely to move more slowly than expected to fulfill its promise to substantially increase refugee admissions.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

During a press briefing April 19, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said the Biden administration has "every intention to increase the cap," but the U.S. refugee program "has also been hollowed out in terms of personnel, staffing and financial and funding needs."

That means the administration is unlikely to meet its goal of admitting as many as 62,500 refugees this year, Psaki said.

Policy shifts under Obama, Trump and Biden

The rules for refugees are different than for the people who arrive in the U.S. seeking asylum, although the same federal agency works with both categories of migrants. To apply for admission as a refugee, people must be outside the U.S. and must demonstrate to a U.S. immigration official overseas that they were persecuted or fear persecution in their home country due to race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. Refugees arrive here legally after passing background checks and other screenings.

By contrast, asylum seekers must be physically present in the U.S. to request asylum. People can apply for the protection whether they arrived here with or without authorization, but must meet specific criteria to be granted protection.

It’s up to the president, in consultation with Congress, to determine the maximum number of refugees who are allowed into the United States each fiscal year. (The federal fiscal year starts Oct. 1 and ends Sept. 30.)

Before leaving office in January 2017, President Barack Obama said that the United States should let in as many as 110,000 refugees in the year ending Sept. 30, 2017. When Trump took over, he said that was too much, and capped it at 50,000. And he continued to lower the cap every year he was in office. The cap he set for fiscal year 2021 — 15,000 — is the lowest ever set since the U.S. refugee admissions program was created in 1980.

As a candidate, Biden said he would aim for an annual target of 125,000 refugee admissions "and will seek to further raise it over time commensurate with our responsibility, our values, and the unprecedented global need."

In early February, Biden signed an executive order that he said would position the U.S. to raise refugee admissions to 125,000 for fiscal 2022, the first full fiscal year of his administration.

Later that month, his administration sent a report to Congress proposing the admission of 62,500 refugees for the current fiscal year, up from Trump’s cap of 15,000.

An 'aspirational goal' no longer looks realistic

On April 16, the administration made two announcements that sparked confusion and signaled a change of plan.

First, it said that "the admission of up to 15,000 refugees remains justified … should 15,000 admissions under the revised allocations for FY 2021 be reached prior to the end of the fiscal year and the emergency refugee situation persists, a subsequent presidential determination may be issued to increase admissions, as appropriate."

After news reports cited the 15,000 as a 2021 cap, Democratic lawmakers, including Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, said that was "unacceptable."

Later that day, Psaki said that a final cap for 2021 would be announced by mid-May. She said that the initial goal of 62,500 seemed "unlikely," due to a "decimated refugee admissions program we inherited, and burdens on the Office of Refugee Resettlement."

In the meantime, Psaki said, Biden had taken "immediate action to reverse the Trump policy that banned refugees from many key regions."

Psaki said on April 19 that the 62,500 was "an aspirational goal." But since that goal was set, she said, there’s been an increase in unaccompanied minors arriving at the southern border and "it took us some time to recognize how hollowed out the systems were."

Duties of the Office of Refugee Resettlement

Psaki pointed to burdens on the Office of Refugee Resettlement. That office, which is part of the Health and Human Services Department, oversees "both the resettling of refugees as well as unaccompanied children" arriving at the southern border requesting asylum, she said.

The services offered to each group are different, said Randy Capps, director of research for U.S. programs at the Migration Policy Institute.

When children arrive alone at the border, immigration officials transfer them to the care and custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which houses them temporarily until they are placed with a sponsor in the U.S. (usually a family member). Typically, children are placed in state-licensed facilities funded by the federal office.

For refugees, the Office of Refugee Resettlement staff primarily work on grants and contracts to refugee service agencies, mostly nonprofits, Capps said. The staff doesn’t fund shelter programs for refugees, but it helps them with employment services, cultural orientation and assistance to food programs and other services.

Another factor that could affect the Biden administration's ability to boost refugee admissions is that many of the immigration staff around the world who screen refugees were reassigned during the Trump administration to handle asylum cases within the U.S. and other tasks, Capps said.

Psaki said there "have been assessments about reprogramming of funds" to handle both refugee admissions and the influx of migrants arriving at the border. She said she was not aware of any request to Congress for supplemental, emergency funding for the Office of Refugee Resettlement.

During the Obama administration, the U.S. experienced an influx at the southern border, but was still able to admit about 75,000 refugees per year, Capps said.

Refugees approved and waiting for admission

The latest federal data shows that from October through the end of March, the U.S. admitted 2,050 refugees.

Overall, there are 35,000 refugees already approved for resettlement in the United States, according to Amnesty International USA.

If the U.S. has already done background checks and other screening for 35,000 refugees, then the administration should be able to admit at least that many this fiscal year, Capps said.

The longer the U.S. waits to raise the admission ceiling, though, the greater the chances that some of those security screenings will expire and have to be repeated, Capps said.

A long wait could also diminish the ability of social-service agencies to help resettle refugees.

As the Trump administration cut refugee admissions, some nonprofits that help resettle refugees closed or cut back staffing. The groups have recently said they can handle an increase in refugee arrivals, Capps said, but "the longer that we have the refugees coming at low levels, the more damage it does to the capacity to accept them."

Our Sources

Rev.com, Press Secretary Jen Psaki White House Press Conference Transcript, April 19, 2021

Phone interview, Randy Capps, director of research for U.S. programs at the Migration Policy Institute, April 19, 2021

Phone interview, David Bier, immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute, April 19, 2021

Rev.com,

WhiteHouse.gov, Memorandum for the Secretary of State on the Emergency Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2021, April 16, 2021; Statement by Press Secretary Jen Psaki on the Emergency Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2021, April 16, 2021

State.gov, Report to Congress on the Proposed Emergency Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2021, Feb. 12, 2021

Medium, Joe Biden — My Statement on World Refugee Day, June 20, 2020

Amnesty International USA, By Maintaining Lowest Refugee Admissions in United States Resettlement History, President Biden Turns His Back on Refugees Around the World, April 16, 2021

PolitiFact, Donald Trump’s immigration promises: failures and achievements, July 27, 2020

PolitiFact, Biden Promise Tracker — Increase refugee admission, last updated Feb. 5, 2021

Rev.com, President Joe Biden's speech Feb. 4, 2021

White House, Executive Order on Rebuilding and Enhancing Programs to Resettle Refugees and Planning for the Impact of Climate Change on Migration, Feb. 4, 2021

Twitter, @AOC tweet, @SenatorDurbin tweet, April 16, 2021

Congressional Research Service, FY2021 Refugee Ceiling and Allocations, Nov. 3, 2020; Refugee Admissions and Resettlement Policy, updated Dec. 18, 2018

Acf.hhs.gov, Children Entering the United States Unaccompanied: Section 2, Last Reviewed Date: February 17, 2021; Unaccompanied children program overview; Children Entering the United States Unaccompanied: Introduction

USCIS.gov, Asylum, Refugees, Refugee Processing and Security Screening

State Department data on refugee admissions Oct. 1, 2020 through March 31, 2021