Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

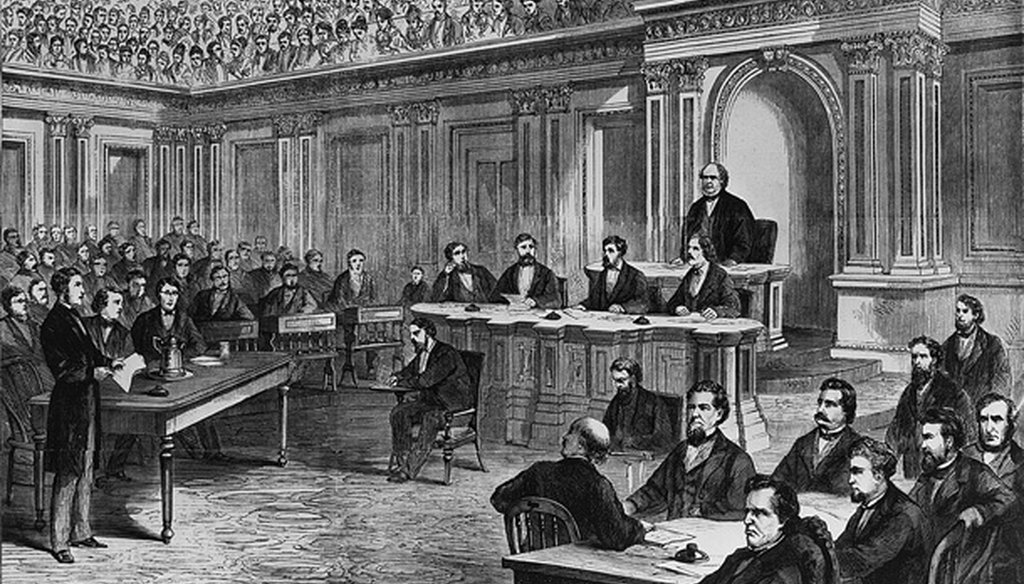

The impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson in 1868.

As the House impeachment inquiry against President Donald Trump grinds forward against the wishes of the White House, we decided to answer some basic questions about the impeachment process both today and in American history.

Here are nine questions and answers.

The Constitution lays out the basics of impeachment, but it does not spell out rules and procedures. It says the U.S. House of Representatives "shall have the sole Power of Impeachment," the Senate "shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments," and when a president is tried "the Chief Justice shall preside." A two-thirds vote for conviction means the person is removed from office.

But the rules and procedures for an impeachment are not written in the Constitution, or in a statute.

More than anything, the procedural details are derived from historical precedent, from the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson in the 1860s to that of President Richard Nixon in the 1970s and President Bill Clinton in the 1990s.

During past impeachments, once the full House authorized an impeachment inquiry, the House Judiciary Committee took the lead in conducting an investigation, holding hearings on proposed articles of impeachment, and voting on whether to approve them.

The procedure in the current impeachment has been different. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., has instructed three committees — Intelligence, Oversight and Foreign Affairs — to proceed with an investigation. The three committees will then transfer evidence to Judiciary, which will be responsible for drafting any articles of impeachment.

This is important because the White House has used it to argue that it doesn’t need to answer House subpoenas for testimony. (It’s widely speculated that Pelosi is holding off on a vote to protect members of her caucus representing Trump-friendly districts.)

We found wide agreement among historians that Pelosi doesn’t need to hold such a vote right now.

"The Constitution does not require any such approval as a part of the process that the House may use in an impeachment proceeding," said Michael Gerhardt, University of North Carolina law professor and author of "Impeachment: What Everyone Needs to Know."

"In fact, the Constitution says that the House not only has ‘the sole power to impeach’ but also that it may devise whatever rules it deems appropriate for internal governance. That includes impeachment," he said.

Jeffrey A. Engel, founding director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University and co-author of "Impeachment: An American History," agreed. "It is an insult to democracy and a thorough repudiation of the idea of separation of powers to suggest that a duly appointed committee of Congress does not inherently have the right of oversight," he said.

But we found a difference of opinion on whether this is a wise decision politically.

James D. Robenalt, attorney with the firm Thompson Hine LLP and creator of a continuing legal education class on Watergate, was one of several sources who said Pelosi’s course so far has costs. "It makes the subpoena power a little more tenuous, and it allows the Republicans to contend that there is no real impeachment process underway," he said.

RELATED: Poynter offers a live webinar on impeachment with PolitiFact journalists. Sign up here

Experts pointed to a variety of differences between the Trump impeachment process and those that went before.

The differences begin with the substance of the charges. All prior presidential impeachments have concerned domestic issues — the aftermath of the Civil War in Johnson’s case, the Watergate burglary and coverup under Nixon, and the Monica Lewinsky affair for Clinton. By contrast, Trump’s impeachment is focusing on the accusation that Trump sought a quid pro quo with Ukraine to find dirt on a potential Democratic challenger, Joe Biden.

Another difference relates to the tactics of the key players.

"Certainly not Clinton, and not even Nixon, mirrored Trump in so vehemently and personally attacking congressional investigators and any and all critics and accusers, including members of their own party," said Allan J. Lichtman, an American University political scientist and author of The Case for Impeachment.

This fiery approach is going hand in hand with a refusal to participate in the inquiry, outlined in an Oct. 8 White House letter.

And while congressional Republicans could eventually change their stance as the investigation goes forward, few have so far shown a willingness to break from Trump in significant ways. Some congressional Republicans have openly supported Trump’s assertion that the allegations against Trump are dubious.

This contrasts with the Nixon impeachment, when "on both sides there was a pretty universal acknowledgement that the charges being investigated were very important and that it was necessary to get to the bottom of what happened," said Frank O. Bowman III, a University of Missouri law professor and author of the book, "High Crimes and Misdemeanors: A History of Impeachment for the Age of Trump." "No one suggested that there’s nothing to see here."

Another first: Trump is facing possible impeachment about a year before running for reelection. By contrast, both Nixon and Clinton had already won second terms when they were impeached. (Johnson was such an outcast within his own party that he would have been an extreme longshot to win renomination, historians say.)

On the eve of impeachment for both Nixon and Clinton, popular support for impeachment was weak — 38% for Nixon and 29% for Clinton, according to a recent Axios analysis. (There was no public opinion polling when Johnson was president.)

From that point, the two presidents’ fates in the polls diverged. In the matter of a few months, support for Nixon’s impeachment rose to 58%. By contrast, public backing for Clinton’s impeachment never went much higher than its initial level.

As for Trump, a Washington Post-Schar School poll released Oct. 8 found that 58% of Americans supported the House’s decision to open an impeachment inquiry of Trump, and that 49% went further and said that the Senate should vote to remove Trump from office.

Such numbers indicate a much weaker position for Trump than for either Nixon or Clinton.

"It took about a year into the Nixon investigations for public sentiment on impeachment to reach the level it had for Trump just a few days into the impeachment inquiry," Lichtman said. "And public sentiment for the impeachment of Bill Clinton never reached current levels for Trump."

Nixon’s experience suggests that under threat of impeachment, "a president’s support can erode extraordinarily rapidly," Engel said. At the same time, he added, the substance of the allegations matter.

During Clinton’s impeachment, "people decided there was a difference between lying about an affair and an affair of state," Engel said. The Republicans’ decision to push impeachment in the face of strong public headwinds made Clinton "seem as if he were the only adult in the room."

During the Nixon era, the media landscape was far more centralized than it is today. It was dominated by a few TV networks and a handful of national newspapers.

Things had changed by the time Clinton was impeached — cable news existed and talk radio had become a key outlet for pro-impeachment Republicans. But social media didn’t exist, and cable news wasn’t as ideologically polarized as it is today.

During Watergate, "you didn’t have CBS and ABC duking it out all day long," said Philip C. Bobbitt, a University of Texas law professor and author of "Impeachment: A Handbook, New Edition."

This media environment has directly shaped the impeachment process, historians said.

"The proliferation of news outlets and 24/7 news coverage and commentary puts pressure on the actors in the process to reach results sooner rather than later," Gerhardt said. "At the same time, the advent of social media allows for the president to have an even bigger bully pulpit than ever before" to ensure compliance with the party line.

Ideological polarization has produced high levels of distrust of the media -- a sea change from the prevailing sentiment during Watergate, Bowman said.

During Nixon’s impeachment, "people counted on the media to serve as arbiters of truth," he said. "Obviously, we don’t have that now."

The Senate could probably refuse to try an impeachment. While the Constitution stipulates that the Senate has the "sole power to try," it does not force the chamber to do so.

"I would interpret this as authority to try, but not a requirement to try," said Steven Smith, a political scientist at Washington University in St. Louis.

Experts agreed that the spirit of the Senate rules on impeachment, written in 1986, express an expectation that the Senate would hold a trial if the House approved impeachment articles.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., has said he’s obligated to hold a trial. But both he and Trump have a track record of upending political expectations, experts noted.

Burdett A. Loomis, a political scientist at the University of Kansas, cited the example of McConnell’s norm-defying refusal to hold a hearing on President Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominee, Judge Merrick Garland, with backing from then-candidate Trump.

The form of a trial, and how extensive it is, is uncertain. "I think McConnell would slow-walk it to a stop, maybe letting the voters decide, even if that was risky," Loomis said.

Experts say that McConnell and Chief Justice John Roberts would probably have a fairly free hand in shaping a Senate trial following impeachment, but the contours remain unknown.

McConnell and Democratic leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., could haggle over such issues as whether to appoint a committee to receive testimony and evidence, what time limits should be set, and when votes are held, Smith said.

The uncertainty about Senate process stems from the rarity of the process. Nixon resigned before the House could vote to send articles to the Senate, leaving just one precedent -- Clinton’s trial — in the past century and a half.

The lack of hard-and-fast procedures for a Senate suggests that winning support of individual senators will be important for setting procedures, Engel said.

Experts say the Senate could take a third path that’s different from removal or acquittal. But to do it, senators would probably have to officially acquit first and then approve a separate measure to censure the president.

Democrats might see this as letting Republicans off the hook.

Meanwhile, the example of Andrew Johnson suggests that even an impeachment without a removal can serve to rein in a president, wrote Gregory P. Downs, a historian at the University of California-Davis, in the Washington Post. He cited Johnson’s more accommodationist approach after impeachment than before.

"The trial itself, not just the verdicts, can be an important tool for restraining presidents who misuse the authority of their office," Downs wrote.

There is no formal time limit for the impeachment process. However, experts say they expect the current process to wrap up before Election Day 2020 — likely well before.

"All signs point to a relatively speedy impeachment inquiry, although the torrent of new info could string it out," said Loomis of the University of Kansas.

Robenalt suggested that impeachment trial could come to a close in spring 2020. "If true to form, the Senate trial would take place within three months, perhaps faster," he said, citing the impeachment trials of Johnson and Clinton. He said that impeachment was "likely to be a campaign issue" for both sides.

The impeachments of both Nixon and Clinton did tend to curb legislative action by soaking up all the attention in Washington, historians say.

Notably, in Nixon’s case, the impeachment process weakened the president’s hand in negotiating a peace treaty to end the Vietnam War, Robenalt said. During Clinton’s impeachment, little significant lawmaking got done.

Bobbitt, who worked for Clinton during impeachment, said that "it took tremendous energy and we had to turn all of our attention to impeachment."

That said, all experts agreed that the current gridlock between the Republican president and Senate and the Democratic House means that not much legislation is moving quickly anyway.

"The Senate is doing so little that spending a week or ten days on a trial is going to have little effect on legislative action," Smith said.

CORRECTION (Oct. 29): This article has been updated to include the House Oversight Committee among the congressional committees leading the investigations as part of the House impeachment inquiry.

Our Sources

Axios, "Trump's impeachment poll warnings," Oct. 6, 2019

Washington Post, "Poll: Majority of Americans say they endorse opening of House impeachment inquiry of Trump," Oct. 8, 2019

Gregory P. Downs, "Impeachment is the right call even if the Senate keeps President Trump in office," Oct. 7, 2019

PolitiFact, "How would an impeachment inquiry against Donald Trump work?" Sept. 24, 2019

PolitiFact, "Ask PolitiFact: Answers to reader questions about the Trump impeachment inquiry, Hunter Biden," Oct. 8, 2019

Email interview with Burdett A. Loomis, political scientist at the University of Kansas, Oct. 7, 2019

Email interview with Steven Smith, political science professor at Washington University in St. Louis, Oct. 7, 2019

Email interview with Allan J. Lichtman, American University political scientist and author of The Case for Impeachment, Oct. 7, 2019

Email interview with Jeffrey A. Engel, director of the Southern Methodist University Center for Presidential History and a contributor to Impeachment: An American History, Oct. 7, 2019

Email interview with Frank O. Bowman III, University of Missouri law professor and author of the forthcoming book, High Crimes and Misdemeanors: A History of Impeachment for the Age of Trump, Oct. 7, 2019

Email interview with Michael Gerhardt, University of North Carolina law professor and author of Impeachment: What Everyone Needs to Know, Oct. 7, 2019

Email interview with James D. Robenalt, attorney with the firm Thompson Hine LLP and creator of a continuing legal education class on Watergate, Oct. 7, 2019

Email interview with Philip C. Bobbitt, University of Texas law professor and author of Impeachment: A Handbook, New Edition, Oct. 7, 2019

Email interview with Stephen M. Griffin, Tulane University law professor and author of American Constitutionalism: From Theory to Politics, Oct. 8, 2019