Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg participate in a media conference at NATO headquarters in Brussels on Dec. 16, 2021. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

NATO, established in 1949, now includes 30 member countries and has been open to new members since then. All NATO decisions are made by consensus among members.

-

In 2008, Ukraine requested a NATO membership action plan, which puts aspiring NATO members on track to potentially join the alliance by helping them to prepare for possible future membership. The alliance’s member nations did not agree by consensus to enter Ukraine into the program, but they did declare that Ukraine “will become” a member.

-

Ukraine has gone through several presidents, revolutions and changes since 2008, but the country’s standing with regard to NATO membership is largely the same now as it was then, experts said. Joining NATO remains a goal for Ukraine, but no consensus has been reached among the member nations in the face of Russia’s continued aggression.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has long cited NATO’s expansion into Eastern Europe as a pretext for his country’s invasion of neighboring Ukraine.

Ukraine remains outside of NATO despite its efforts to join the Western military alliance, which was established in 1949 and has swelled to include 30 member countries. In March, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy conceded that Ukraine was unlikely to be admitted into NATO.

A reader asked PolitiFact about the history of Ukraine’s bid to become a member nation.

"My friend and I are disagreeing about NATO and Ukraine," the reader wrote in an email. "My understanding is that Ukraine asked to join NATO in 2012. NATO responded with no, but maybe later. I think that Zelenskyy asked NATO recently to join now and was turned down. My friend thinks that Zelenskyy is saying no to joining NATO now."

PolitiFact ran the question by NATO and five foreign policy experts, including several who held positions with NATO or the U.S. State Department. The answer is complicated.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

"Zelenskyy expressed interest in NATO up until the invasion," said Steven Pifer, a Ukraine expert affiliated with the Brookings Institution and Stanford University. "NATO has never turned him down. But it has never said yes, even to a (membership action plan)."

The 2008 Bucharest Summit

Ukraine first publicly expressed interest in joining NATO in 2002, said Pifer, who was the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine from 1998 to 2000.

In 2006, under former President Viktor Yushchenko, Ukraine became more serious about NATO membership, Pifer said. The country was angling to receive a membership action plan, or MAP, until Yushchenko appointed Russian-friendly Viktor Yanukovych as prime minister, and that put the idea to rest. A MAP sets aspiring NATO members on track to potentially join the alliance by providing them with political and technical advice to help them prepare for future membership.

"This process effectively opens the door to membership of the alliance," said John Lough, an associate fellow in the Russia and Eurasia program at Chatham House, a London-based think tank, who served from 1995 to 1998 as NATO’s first representative based in Moscow.

In January 2008, Yushchenko called again for a MAP, this time with the support of a new prime minister and the speaker of Ukraine’s parliament, Pifer said. But all NATO decisions are made by consensus, rather than voting. At NATO’s Bucharest summit later in 2008, member countries did not reach a consensus on Ukraine’s request.

"NATO membership is something which is decided by 30 allies," NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said April 5, recounting the history at a press conference. "Since 2008, NATO allies have provided support to Ukraine. But we have not had consensus on granting membership."

Former U.S. President George W. Bush, Ukraine President Viktor Yushchenko and NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer before a NATO summit in Bucharest, Romania on April 4, 2008. (AP)

While the NATO members in Bucharest did not agree to put Ukraine on the path toward membership, they did make a broader commitment to eventually admit Ukraine.

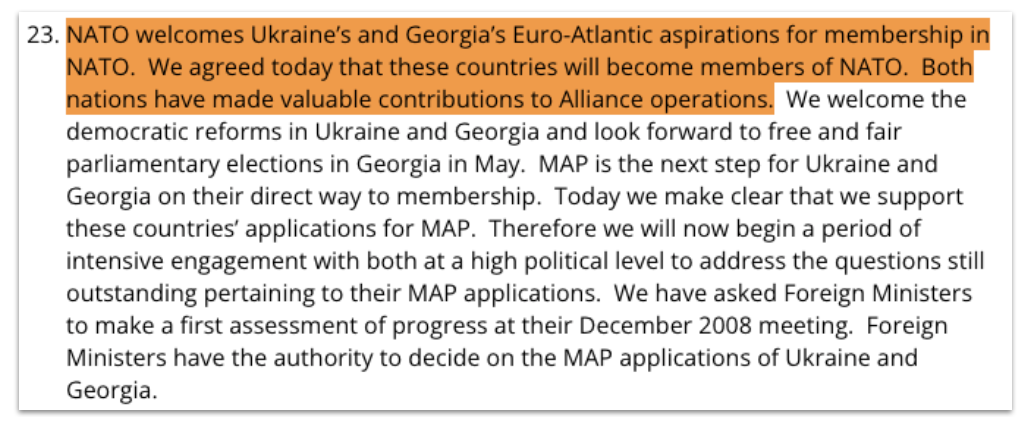

"NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO," the alliance said in the official "Bucharest Summit Declaration" issued April 3, 2008. "We agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO."

The line was a concession to U.S. President George W. Bush, whose administration had lobbied to give Ukraine a membership action plan but failed to persuade all the other allied leaders, experts said.

"But it was arguably the worst of all worlds," said Christopher Preble, co-director of the Atlantic Council’s New American Engagement Initiative. "Neither a formal ‘no’ nor a formal ‘yes.’"

Ivo Daalder, president of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and the U.S. ambassador to NATO from 2009 to 2013, said it was "a compromise that satisfied no one."

"Since a (membership action plan) is necessary to prepare an aspirant for membership, the promise of future membership was just that: a promise," Daalder said. "Since 2008, until the days before Russia's invasion, nothing changed."

An open door, but little movement

For a few years starting in 2010, Ukraine adopted a non-aligned status that was codified into law with Yanukovych as president, meaning it could not join military alliances.

After a revolution in 2014 that ousted Yanukovych, and as Russia scaled up its aggression in Crimea and the Donbas region, Ukraine scrapped the non-aligned status.

Ukraine has since amended its constitution to explicitly spell out its desire to join NATO, and joining NATO remains the official policy of Ukraine, Daalder said.

The country resumed its "determined efforts" to receive a membership action plan from NATO under President Petro Poroshenko, who held office from 2014 to 2019, Lough said. But neither Poroshenko nor his successor Zelenskyy have successfully gotten the ball rolling.

"Up until a few weeks ago, Zelenskyy was very clear that Ukrainian membership in NATO was central to Ukraine’s national security objectives," said Joshua Shifrinson, associate professor of international relations at Boston University.

Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy speaks during a meeting of the UN Security Council on April 5, 2022. (AP)

NATO, meanwhile, has repeatedly said its door remains open. In a statement to PolitiFact, a NATO official said the alliance has never shut out aspiring new members, and that Russia has no veto or right to influence its neighboring countries in their pursuit of NATO membership. U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said in 2021, "We support Ukraine membership in NATO."

A consensus among NATO members is still required to admit new countries, however. Those members remain divided over the wisdom of welcoming Ukraine into their ranks, experts said, in large part because admitting NATO could mean angering or entering into war with Russia.

The NATO allies have supported Ukraine against Russia’s invasion in other ways, including by supplying weapons to Ukraine and implementing massive sanctions on Russia.

Zelenskyy in March said that despite hearing for years about the alliance’s "apparently open door," it was "clear that Ukraine is not a member of NATO." He has petitioned the West for other security guarantees in the event that Ukraine remains neutral.

"One could say this is placating Russia, but it might simply be a recognition of reality," Preble said. "Formal NATO membership is unlikely, and he’s exploring all possible options."

RELATED: Fact-checking claims NATO, US broke promise to Russia about extending eastward

Our Sources

Reader question, April 11, 2022

NATO, "Press conference," April 5, 2022

The Guardian, "Ukraine will not join Nato, says Zelenskiy, as shelling of Kyiv continues," March 15, 2022

NATO, "Relations with Ukraine," March 11, 2022

NATO, "Consensus decision-making at NATO," Oct. 2, 2020

NATO, "Membership Action Plan (MAP)," March 23, 2020

NATO, "Bucharest Summit Declaration," May 8, 2014

PolitiFact, "Fact-checking claims that NATO, US broke agreement against alliance expanding eastward," Feb. 28, 2022

Email correspondence with NATO, April 13, 2022

Email interview with Christopher Preble, co-director of the New American Engagement Initiative in the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security at the Atlantic Council, April 13, 2022

Email interview with John Lough, associate fellow of the Russia and Eurasia Programme at Chatham House, April 12, 2022

Email interview with Steven Pifer, nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a fellow at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University, April 12, 2022

Email interview with Joshua Shifrinson, associate professor of international relations at Boston University, April 12, 2022

Email interview with Ivo Daalder, president of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, April 12, 2022