Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines are administered at Providence Edwards Lifesciences vaccination site in Santa Ana, Calif., on May 21, 2021. (AP/Hong)

A viral Instagram post claiming the COVID-19 vaccines are far less effective than advertised is conflating different measures of efficacy to leave a misleading impression.

The COVID-19 vaccines are highly effective. The Pfizer vaccine’s 95% efficacy, for example, means that the people who received the vaccine in clinical trials had a 95% lower risk of becoming infected than those who received a placebo.

A separate measure of vaccine efficacy was the subject of a Lancet Microbe commentary — not a peer-reviewed study. The commentary did not argue that the vaccines do not work, or that the widely reported efficacy figures were inaccurate. An author of the commentary told PolitiFact that the Instagram post misinterprets it.

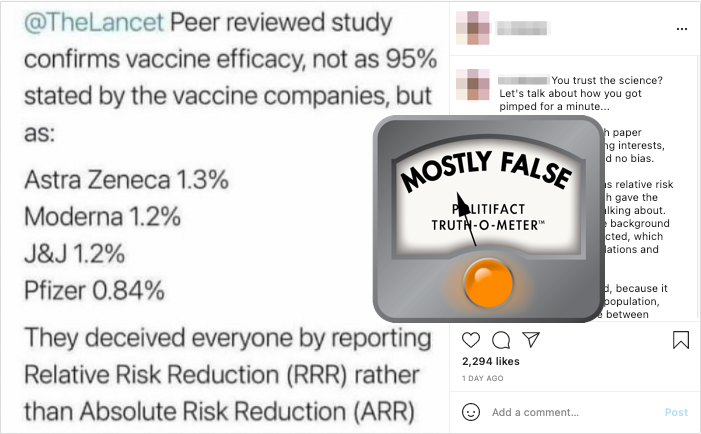

A widespread Instagram post argues, wrongly, that new information has shown the COVID-19 vaccines to be far less effective than advertised.

The post errs by conflating two different calculations used to gauge the efficacy of vaccines, and it makes false conclusions based on that error.

"The Lancet peer-reviewed study confirms vaccine efficacy, not as 95% stated by the vaccine companies, but as: AstraZeneca 1.3%; Moderna 1.2%; J&J 1.2%; Pfizer 0.84%," says the May 26 Instagram post, which received thousands of likes. "They deceived everyone by reporting Relative Risk Reduction (RRR) rather than Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR)."

"Your Pheyezur schmaccine just went from 95% down to 0.84% effective," the Instagram post adds, in a reference to the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine’s 95% efficacy in clinical trials.

The post and others like it were flagged as part of Facebook’s efforts to combat false news and misinformation on its News Feed. (Read more about our partnership with Facebook.) Misspelling vaccine terms is a common tactic used on social media to evade the tools used by fact-checkers.

The article cited in the post is a Lancet Microbe commentary, not a peer-reviewed study. And one of its authors, along with other experts, said the post’s interpretation is misleading.

"It is extremely disappointing to see how information can be twisted," said Piero Olliaro, a professor of poverty related infectious diseases at the University of Oxford’s Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health. "We do not say vaccines do not work."

A screenshot of a May 26, 2021, Instagram post wrongly claiming the COVID-19 vaccines are less effective than advertised.

The person behind the Instagram post did not respond to requests for comment.

The COVID-19 vaccines available for use in the U.S. are highly effective. Pfizer’s two-dose vaccine, for example, was found in clinical trials to be 95% effective at preventing COVID-19 infection, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Instagram post says that based on new information, the vaccine "went from 95% down to 0.84% effective." But that’s not the case. The post mixes up two different measures of vaccine efficacy that can be calculated from the clinical trial data.

Both measures are expressed as percentages, but they describe different things. Broadly speaking, one describes the probability of avoiding infection by getting vaccinated. The other represents the proportion of people in a group who avoided infection as a result of getting vaccinated, given their baseline risks. The commentary highlighted this second measure.

When we hear that the Pfizer vaccine has 95% efficacy, that doesn’t mean 5% of recipients will get COVID-19. Instead, it means that the people who received the vaccine in clinical trials had a 95% lower chance of becoming infected than those who received a placebo.

This vaccine efficacy figure is what epidemiologists refer to as the relative risk reduction.

This is the measure that’s commonly reported for vaccines, including the yearly flu shot, said Natalie Dean, assistant professor of biostatistics at the University of Florida. It’s the "most immediately meaningful" indicator of efficacy because it’s easily generalizable.

Imagine that "one version of you is vaccinated and one version of you is unvaccinated," Dean said. For a vaccine with 95% efficacy as measured by relative risk reduction, "the vaccinated version of you has a 95% lower risk, lower chance of getting sick."

The other measure is known as absolute risk reduction. This measure accounts for people’s baseline risks of getting COVID-19. It changes across different groups and timeframes, depending on how likely a certain population is to get COVID-19 in the first place, without protection from the vaccine.

Richard Watanabe, a professor of preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, defined absolute risk reduction as "the proportion of people in the population who do not develop disease" as a result of getting the COVID-19 vaccine. Put differently, it’s the number of percentage points a population’s risk goes down by taking the vaccine.

"You can imagine that different people will have different baseline levels of risk, depending on where they live, what their occupation is, all different things," Dean said. "The people who had a larger risk at baseline will have a larger benefit (from the vaccine) in those absolute terms."

Both efficacy figures can be drawn from the clinical trial data, by comparing the percentage of vaccinated participants who got COVID-19 with the percentage of unvaccinated participants who got COVID-19. The relative risk reduction is calculated using a ratio that divides one percentage by the other, while the absolute risk reduction takes the arithmetic difference between the two. (The mathematical formulas are listed in a table with the Lancet commentary.)

The numbers that appeared in the Instagram post come from the Lancet commentary and were calculated by Olliaro’s team. But they’re "on a totally different scale" than the 95% and other vaccine efficacy numbers that were widely reported, Dean said.

The absolute risk reduction "looks much smaller than the relative effect," said Matthew Fox, a professor of epidemiology at Boston University. "But remember, over the time the vaccine trials are run, only a percentage of those in the study were exposed to COVID, so most people would not be infected even if not vaccinated. So a 1%-2% absolute reduction is a big reduction, and could result in dramatically fewer infections when we vaccinate the population."

On its own, the absolute risk reduction can be hard to understand, Olliaro said. But the figure can help with policymaking, because it can be used to estimate how many people need to be vaccinated in a given population in order to prevent one additional case of COVID-19.

The post’s claim that the COVID-19 vaccine developers "deceived everyone" wrongly suggests that a cover-up was in effect to make the shots seem more efficacious than they are.

"The drug companies are not trying to hide anything," Watanabe said. "If you were a competent scientist you could, like the authors of the Lancet article, calculate the other metrics by hand using the data reported in the original New England Journal of Medicine papers."

Second, the post falsely claims that the Lancet commentary proved the reported vaccine efficacy figures — such as Pfizer’s 95% — were wrong. Those figures have since been backed by real-world studies, including one that found the Pfizer shot to be 90% effective.

Olliaro, who co-wrote the Lancet commentary, said it’s wrong to interpret the commentary — which has led to some back-and-forth among scholars — as saying the vaccines don’t work.

The commentary argued that vaccine developers should more prominently report absolute risk reductions alongside relative risk reductions in order to facilitate public health decisions and compare vaccines, Olliaro said.

But the "bottom line," Olliaro said, is that "these vaccines are good public health interventions."

An Instagram post says, "The Lancet peer-reviewed study confirms vaccine efficacy, not as 95% stated by the vaccine companies, but as: AstraZeneca 1.3%; Moderna 1.2%; J&J 1.2%; Pfizer 0.84%." The post says the vaccine developers "deceived everyone."

The Lancet Microbe article cited as evidence was a commentary, not a peer-reviewed study. And the commentary did not say that the COVID-19 vaccines don’t work, or that the widely reported vaccine efficacy numbers — such as Pfizer’s 95% efficacy — were inaccurate.

The post errs by conflating two different efficacy measures to give the false impression that the vaccines are far less effective than advertised, and that the vaccine developers gave inaccurate numbers to the public.

We rate this Instagram post Mostly False.

Instagram post, May 26, 2021

The Lancet Microbe, "COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and effectiveness—the elephant (not) in the room," April 20, 2021

The University of Western Australia, "Understanding absolute and relative risk reduction," accessed May 27, 2021

The Lancet Microbe, "COVID-19 vaccines: effectiveness and number needed to treat – Authors' reply," May 14, 2021

The Lancet Microbe, "COVID-19 vaccines: effectiveness and number needed to treat," May 14, 2021

Wired, "The Statistical Secrets of Covid-19 Vaccines," May 6, 2021

The New York Times, "What Do Vaccine Efficacy Numbers Actually Mean?" March 3, 2021

Natalie E. Dean on Twitter, Sept. 28, 2020

Phone interview with Natalie E. Dean, assistant professor of biostatistics at the University of Florida, May 27, 2021

Email interview with Richard M. Watanabe, professor of preventive medicine and associate dean for health and population science programs at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, May 27, 2021

Email interview with Matthew Fox, professor of epidemiology and global health at Boston University, May 26, 2021

Email interview with Piero Olliaro, professor of poverty related infectious diseases at the University of Oxford’s Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, May 26, 2021

In a world of wild talk and fake news, help us stand up for the facts.