Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

The mass shootings in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, weren’t coordinated by a shadowy, leftist branch of the government. The media haven’t "changed the identity" of the shooters, and the Ohio gunman did not actually die in 2014.

But thousands of social media users still shared those conspiracies as a way to suggest the attacks were either planned or didn’t happen at all.

PolitiFact found dozens of Facebook posts that promoted "false flag" conspiracy theories after the mass shootings on Aug. 3 and 4. While the storylines vary, many claim the tragedies were planned by the "deep state," an alleged faction of the government that’s working against President Donald Trump. The purported goal: To push for gun control.

False flag conspiracies aren’t new — misinformers have promoted them after nearly every mass shooting in recent memory. They’re one of the first things fact-checkers look for when covering such atrocities.

And that’s not likely to change anytime soon. So we set out to understand how these claims persist despite routine fact-checking and a total lack of evidence — and why people believe them in the first place.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

From Sandy Hook to Dayton

There have always been conspiracy theories that question whether an event actually happened the way authorities and the media described.

But experts trace the marriage of false flag conspiracies and mass shootings back to 2012, following the attack at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. that left 26 kids and staff members dead.

"The way we’ve been paying attention to it in recent years has really come about from Sandy Hook," said Joseph Uscinski, an associate professor of political science at the University of Miami who researches conspiracy theories.

Alex Jones, owner of the site InfoWars and a known peddler of misinformation, suggested that the tragedy was "fake" and that the shooting was a "false flag" attack coordinated by the government.

It was plainly untrue, and so incendiary that it got a lot of media attention. And so now, with each shooting, it always pops up that it’s a false flag, Uscinski says.

Google Trends data indicate that Uscinski has a point.

Search queries for the term "false flag" over the past five years have spiked during mass shootings, including those at Planned Parenthood in Colorado Springs (November 2015) and the Pulse nightclub in Orlando (June 2016).

Interest peaked during the week of the Las Vegas shooting in October 2017, which inspired widespread false flag conspiracies. And searches for the term shot up again after the El Paso and Dayton attacks.

After Sandy Hook, false flag conspiracies were mostly floated by fringe pundits and misinformers like Jones, which in turn generated outrage headlines. After Las Vegas, Jones’ baseless allegations were accompanied by fake news websites that chimed in with their own flavors of misinformation.

But now, shooting hoaxes migrate from platforms like 4chan and 8chan to Facebook and Twitter — where they’re amplified by users with larger followings. One practice, called astroturfing, involves a group of social media users coordinating to get a hashtag trending on social media to make it look like there’s widespread interest in a specific topic. That’s what happened in spring 2018 after the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla.

"Oftentimes these adversarial narratives are crafted in more fringe or anonymized social media platforms and distributed across hyperpartisan Facebook groups and pages, and amplified across Twitter by astroturfing hashtags that are relevant to the news event," said Ben Decker, founder of digital investigations consultancy Memetica, in a message to PolitiFact.

‘False flags’ on Facebook

For most people, Facebook is still among the biggest sources of shooting misinformation. And even though a lot of conspiracies originate on fringe websites, some cross over onto Facebook for a wider audience.

Most of the false flag conspiracies PolitiFact found about El Paso and Dayton came from pages or users already involved in conspiracy communities like QAnon. The hoaxes took various forms, ranging from photos comparing different shooting suspects to selfie videos casting doubt on media coverage.

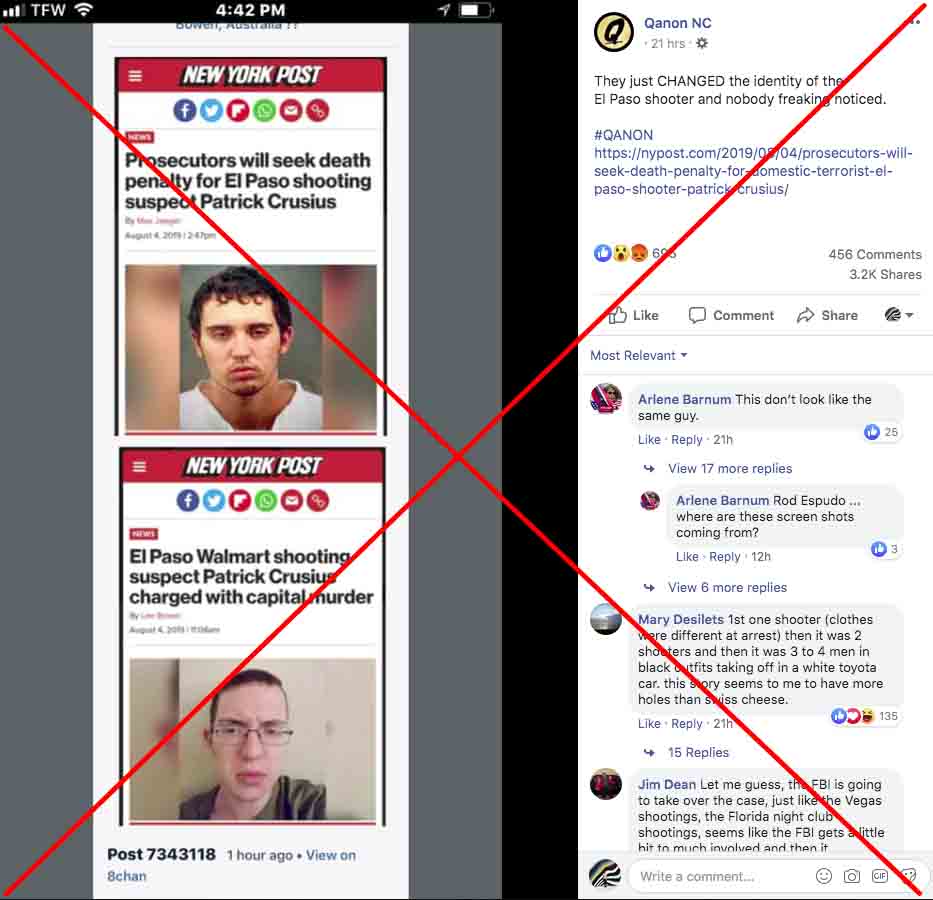

In an example of the former, a Facebook page called Qanon NC posted a side-by-side comparison of two headlines from the New York Post. The first shows a mugshot of the man police have identified as the El Paso gunman, while the second purports to show a photo of the same person. The man in the first mugshot appears to have darker hair and skin than the person in the second.

"They just CHANGED the identity of the El Paso shooter and nobody freaking noticed," the post claimed.

(Screenshot from Facebook)

The media didn’t change the identity of the shooter — they just updated their photos to the mugshot provided by El Paso police. But the post was still shared more than 3,000 times on Facebook, later spreading to platforms like Reddit and 4chan.

Another Facebook user posted a photo of Oprah Winfrey that’s popularly used as a meme with "You get a false flag!" over it. In the caption, the user included a bulleted list of "telltale signs" that the shootings in El Paso and Dayton were planned. (We rated this claim Pants on Fire.)

"If the recent shootings make you feel like taking guns away from citizens is the appropriate next step then congratulations, you’re a typical sheep," the post reads.

Then there was a smattering of selfie videos in which Facebook users used conjecture and speculation to cast doubt that the shootings happened the way news outlets said they did. Several videos, some of which have been viewed tens of thousands of times, featured users with large followings talking to the camera outside or in their cars.

"I have a real strong suspicion that these mass shootings are politically driven by the left!" one user claimed in a video caption.

Seeing is not believing

There’s no good way to measure what people actually believe on social media. But there are a few polls that show hoax narratives do break through to a not-small segment of the population.

One conducted by Farleigh Dickenson in 2016, and cited by Uscinski in 2018, found that 22% of Americans believed it was "possibly or definitely true" that the Sandy Hook massacre was "faked, in order to increase support for gun control." Another representative poll of Floridians, which Uscinski conducted in August 2018, found that about 15% thought mass shootings were hoaxes aimed at taking away people’s guns.

Why? Those false beliefs affirm some people’s worldviews.

"They distrust the media and police, whether because they view the ‘fake news’ and police as complicit with or dupes of the conspiracy," said Mark Fenster, a law professor at the University of Florida who has written extensively about conspiracies, in an email to PolitiFact. "And they either already believe or are susceptible to believe in whatever the claim cites as the reason behind the elaborate set-up."

There are also psychological benefits to believing those claims. Research suggests there are three main reasons why some people rely on conspiracy theories during breaking news.

Mourners bring flowers to a makeshift memorial Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2019, for the slain and injured in the Oregon District after a mass shooting that occurred early Sunday morning in Dayton. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

"The first is epistemic — to gain knowledge and certainty," said Karen Douglas, a professor of social psychology at the University of Kent in the United Kingdom, in an email. "The second is existential — to feel safe and secure. And the third is social — to feel good about the self and the groups we belong to."

Douglas pointed to a study from 2017, which found that conspiracy theories offer some sort of compensation for people who are alienated by society. For false flag hoaxes specifically, Douglas said believers may be trying to blame their political enemies so they don’t have to confront flaws in society that cause gun violence.

"By blaming a small section of people in society for the things that have happened, then they can maintain confidence in the system as a whole," she said.

Conspiracies thrive when they align with a certain political ideology.

"For example, Holocaust denialism is embraced by people with antisemitic attitudes," said Joseph Pierre, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences at the University of California at Los Angeles, in an email. "Similarly, people who are drawn to false flag conspiracies about mass shootings will predictably be those with strong beliefs about gun ownership and gun rights who are mistrustful of government in general and liberals in particular."

When it comes to false flag conspiracies about shootings, social media platforms provide a convenient way for believers to share, collaborate and communicate.

"Delusional beliefs aren’t typically shared," Pierre said. "But the internet has become a safe haven for fringe beliefs such that it’s no longer difficult to find someone who might share a belief — about false flag operations, a flat earth, UFOs and alien abductions, or the Mandela Effect — and point you to others that are just as appealing, however improbable."

Our Sources

Comments from Ben Decker, founder of digital investigations firm Memetica

Current Directions in Psychological Science, "The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories," Dec. 7, 2017

The Daily Dot, "Alex Jones pushes another baseless, grossly inaccurate school shooting conspiracy," accessed Aug. 6, 2019

Email interview with Joseph Pierre, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences at the University of California at Los Angeles

Email interview with Karen Douglas, a professor of social psychology at the University of Kent

Email interview with Mark Fenster, a law professor at the University of Florida

Facebook post, Aug. 4, 2019

Facebook post, Aug. 4, 2019

Facebook post, Aug. 4, 2019

Fairleigh Dickinson University, "Fairleigh Dickinson University’s PublicMind Poll Finds Trump Supporters More Conspiracy-Minded Than Other Republicans," May 4, 2016

Google Trends data, accessed Aug. 6, 2019

Interview with Joseph Uscinski, an associate professor of political science at the University of Miami

Know Your Meme, "Oprah’s ‘You Get A Car,’" accessed Aug. 6, 2019

PolitiFact, "Did the media ‘change the identity’ of the El Paso shooter?’ Nope," Aug. 5, 2019

PolitiFact, "Fifty years after Apollo 11, moon landing hoaxes still thrive online," July 18, 2019

PolitiFact, "Hillary Clinton correct that Austin's Alex Jones said no one died at Sandy Hook Elementary," Sept. 1, 2016

PolitiFact, "Hoaxes, fake news about the Las Vegas massacre," Oct. 2, 2017

PolitiFact, "How Russian trolls exploited Parkland mass shooting on social media," Feb. 22, 2018

PolitiFact, "No, the El Paso and Dayton mass shootings were not ‘false flag’ operations," Aug. 5, 2019

PolitiFact, "QAnon and Donald Trump rallies: What's that about?" Aug. 3, 2019

Poll by Joseph Uscinski and Casey Klofstad, August 2018

Poll from Public Policy Polling, April 2, 2013

PunditFact, "Alex Jones’s file," accessed Aug. 6, 2019

Snopes, "Did the Suspected Dayton Mass Shooter Actually Die in 2014?" Aug. 5, 2019

Snopes, "Was the Sandy Hook Elementary School Shooting a Hoax?" Dec. 15, 2012

The Washington Post, "Five things to know about ‘false flag’ conspiracy theories," Oct. 27, 2018